loading

loading

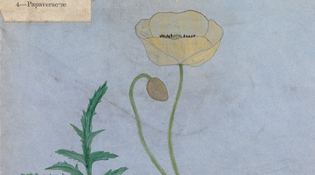

Arts & CultureObject lesson: Miss Rowe of LiverpoolA self-taught Victorian naturalist’s exquisitely presented collection. Elisabeth Fairman is senior curator of rare books and manuscripts at the Yale Center for British Art. Her book “Of Green Leaf, Bird, and Flower”: Artists’ Books and the Natural World (Yale University Press) celebrates the artistry of Miss Rowe and other self-taught naturalists.  Yale Center for British ArtFor each one of the species—some 500—preserved in the herbarium she carefully compiled in 1861, Miss Rowe supplied a blue envelope adorned with a watercolor of a flower. This one bears a yellow poppy and a label with the Latin name of the poppy family. View full imageLike so many Victorians who observed and recorded the natural world, the remarkable Miss Rowe of Liverpool was a self-taught naturalist. We know little about her—the best guess is that she was Elizabeth Rowe, a resident of Liverpool aged 19 in 1861—but we have her extraordinary collection of some 500 preserved plant specimens, identified as hers by her calling card. Miss Rowe’s unique and carefully compiled herbarium is one of the treasures in the department of rare books and manuscripts at the Yale Center for British Art. Miss Rowe joined the newly formed Liverpool Naturalists’ Field Club in the spring of 1861. In this first year, the club attracted more than 500 members. A report in the progressive Popular Science Review noted that “one of the chief causes of their rapid rise and great popularity is the admission of lady members to all their meetings, whether in the open air or in the lecture-hall.” The first order of business at the first meeting was to distribute “amongst the ladies a printed list, headed ‘L. N. F. C. Names of Natural Orders from Dr. Dickinson’s Flora of Liverpool’” (an 1851 monograph). The list included:

Sadly, we do not know if the estimable Miss Rowe won the prize in the end, because at the meeting where the decision was to be announced, the judges ran out of time—owing to the length of the “excellent address” by the invited speaker, Mr. Grindon, Honorary Secretary of the Manchester Naturalists’ Field Club. As a result, the judges “were unable to award the prize to the successful competitress. This part of the proceedings was, therefore, postponed.” It must have been incredibly frustrating to the women in the room. But one hopes that Miss Rowe won. There can be no doubt that she deserved it. Housed in an elegant mahogany box, her specimens were carefully mounted on thin writing paper, labeled in pen and ink, and sorted into genera and species. She had placed each one into an ordinary blue stationery envelope and drawn a watercolor of a flower on the outside; here we see her drawing of a yellow poppy from the family Papaveracea. She added, of course, the correct perforated label from Dr. Dickinson’s Flora. Whether or not Miss Rowe received the first prize awarded by the Field Club, she was singled out later, in a report on the club’s activities, as “a young lady member of this club [who] is remarkably successful in these competitions, and possesses very extensive knowledge in systematic botany.” That is the last we hear of Miss Rowe in the printed reports of the club. More research remains to be done to discover if she continued her natural history pursuits elsewhere. It may be that she no longer had time for such leisure activities. We do know that Elizabeth Rowe, a “spinster,” married 21-year-old William O’Neil, a farrier, that same summer of 1861.

The comment period has expired.

|

|