loading

loading

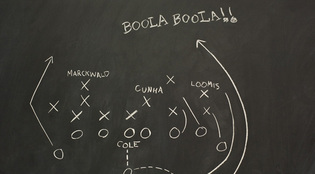

Arts & CultureWho really wrote “Boola Boola”?Disputes over the authorship may never be resolved. But the most likely authors drew heavily from a pair of African American composers. Yale law librarian Fred R. Shapiro is editor of the Yale Book of Quotations.  Photo illustration: John Paul ChirdonView full imageThe authorship of Yale's iconic fight song “Boola Boola” has traditionally been ascribed to Allan M. Hirsh, Class of 1901. In October 2000, Hirsh's grandson, Philip Hirsh ’60, published an essay in this magazine that appeared to be the definitive account of his grandfather's writing of the song. Philip based his conclusions on family history and on a letter he had found in an old box of Yale papers from his grandfather's attic. Allan Hirsh wrote the letter in 1930 to a schoolgirl who had inquired about the “Boola Song.” He answered that he had written the song together with classmates F. M. Van Wicklen, Albert Marckwald, and James L. Boyce on a Friday afternoon in the fall of 1900, and then got a larger group to sing it the next day at a football game. In his article, the younger Hirsh noted the date of the composition -- November 23 -- and that the game in question was the Harvard game, which Yale won in a rout: 28-0. He ended his article: “The song is still euphonious, and the mystery of its origin is solved.” The story of “Boola Boola,” however, is far more complicated than the standard account lets on, and there are question marks and competing claims that cannot easily be dismissed. I record those ambiguities in this column so that a fuller picture is available to future investigators. First of all, we can dismiss as unsubstantiated the belief, widely held in Hawaii, that “Boola Boola” was composed by the Hawaiian musician and businessman Albert R. “Sonny” Cunha while he attended Yale Law School during 1898-1900. When Cunha died in 1933 the New York Times and Washington Post both memorialized him as co-composer of the song. I have corresponded with Hawaiian music scholars and archives, however, and found no solid corroboration of the claims for Cunha. A more substantial, if still minor, question about the Hirsh account is the fact that the November 23 dating is demonstrably impossible. As early as October 19, 1900, the Yale Daily News announced a rehearsal of “the Boola chorus.” In its October 27 edition, the News printed a set of lyrics tailored for an upcoming Princeton game and ending with two unmistakable lines: “Well, a Boola, Bool, Boola, Boola, Bool, / Boola, Bool, Boola, 'oola, Boola, Bool!” The October 29 New Haven Evening Register called it “the ode which is now sung most generally.” A number of additional articles retrieved by searching online databases of historical newspapers also record the new song being sung before November 23. I contacted Philip Hirsh to ask about the discrepancy. He responded that the November 23 dating was not mentioned in his grandfather's 1930 letter, although it “comes from Grandfather and has been repeated by Marckwald” and “is entrenched in family lore.” He concluded that the song's first outing could not have been the Harvard game. Philip also mentioned that Marckwald resented Allan Hirsh for downplaying Marckwald's coauthorship. (Indeed, in the 1901 Class Book Marckwald is credited with the tune and Hirsh with the lyrics.) The tension between the two men culminated in a dramatic deathbed apology by Hirsh.

So far, these issues do not raise major questions about the origins of the song. But the claim of two men with no Yale connection -- Robert Allen “Bob” Cole and Billy Johnson -- appears to shift the role of Hirsh (and his classmates) from creating to adapting. Hirsh himself acknowledged as much, if somewhat obliquely, in his 1930 letter. Cole and Johnson were extremely popular African American singer-songwriters of the time. They wrote, directed, and produced the first full-length musical with an all-black cast and all-black management, which opened on Broadway in 1898. Also in 1898, they copyrighted a song called “La Hoola Boola.” In addition to using the word “Boola,” their song, according to James J. Fuld's authoritative Book of World-Famous Music (1971), has the same melody “virtually note for note in the important bars” as the Yale song. Fuld adds that, when the first edition for piano of “Yale Boola” (with A. M. Hirsh listed as author) was published in 1901, it included a notice: “Adapted by permission of Howley, Haviland & Dresser.” Howley, Haviland & Dresser was the successor publisher of “La Hoola Boola.” In his 1930 letter, Allan Hirsh wrote: “The song was not altogether original with us, but was undoubtedly adapted from some other song but we were unable to definitively designate this song, although later on we did discover that there had been published a song, which at that time was out of print, called 'La Hula Boola,' and the air was quite similar but the time was different.” Given that Hirsh's publisher had felt obligated to get permission for adapting “La Hoola Boola,” Hirsh seems, at the least, to have failed to give proper credit to Cole and Johnson. Finally, the most startling discovery complicating Hirsh's claim to authorship involves his publisher, Charles H. Loomis of New Haven. The Hartford Courant, April 6, 1905, reported: Charles H. Loomis, who published the famous Yale “Boola” march and who has been sued by Allen M. Hirsh, Yale ’01, supposed to be its composer, says now that Mr. Hirsh was not the composer of the march and had no further connection with it than to have his name on the title page. Mr. Loomis says that a number of years ago he purchased from Cole & Johnson the copyright to a composition known as “Laholaboola,” and that, after it was rearranged, it was published under the title of “Boola.” Mr. Hirsh, who was then in Yale, was approached by Mr. Loomis and an agreement was made whereby Mr. Hirsh was to pose as the composer. The Boston Daily Globe elaborated, also on April 6, that Loomis claimed “the Yale man's name was put on the title page only as part of a contract with him to boom [publicize] the piece. . . . He was to push the march and make it popular to the best of his ability.” Loomis countersued, accusing Hirsh of violating his contract. “Both suits were withdrawn,” reported the Daily Globe on October 7, 1905. “By the settlement of the case Loomis becomes owner of the famous song.” Philip Hirsh had not heard of the lawsuit until I sent him the articles. He found it “fascinating” but argues that, unless further evidence comes to light -- such as the legal complaints, or the contract itself -- it is impossible to judge the truth of the two men's competing charges. (Unfortunately, the Connecticut State Library does not preserve trial court pleadings prior to 1933.) Philip adds that his grandfather “was a cheerleader for the football team who was supposed to compose/write and post on the tree in the Vanderbilt courtyard new cheers for each game,” and in that capacity wrote, copyrighted, and published several marches and cheers. Further, “he was an accomplished musician and he was a composer. . . . Thus he quite possibly -- even probably -- knew Loomis and thus the idea of booming the song.” The “Boola Boola” saga is, in the Churchillian phraseology, “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” Is there still a basis for endorsing Hirsh's origination despite all the questions surrounding it? There is some straightforward evidence favoring Hirsh from the Yale Alumni Weekly, the precursor of this magazine. On December 19, 1900, the Weekly noted that some said Hirsh “brought it ['Boola'] from the South.” The March 6, 1901, issue stated that “Mr. Hirsh did a real public service in bringing it out.” According to the April 24, 1901, issue, “The 'Yale Boola,' composed by A. M. Hirsh ’01, was played by Sousa's band at the performance in New Haven.” The early dates of the Yale Alumni Weekly attributions, as well as their proximity to the Yale milieu in which the song incubated, strengthen Hirsh's claim. Charles H. Loomis's allegations, uncorroborated and made in the context of litigation, should be taken with a grain of salt. The Hirsh legend certainly slights the contributions of Cole and Johnson, and perhaps those of Marckwald and others. But despite all the confusion, the hypothesis of Hirsh's authorship still appears to be the most plausible one until such time as more evidence may be unearthed.

The comment period has expired.

|

|