loading

loading

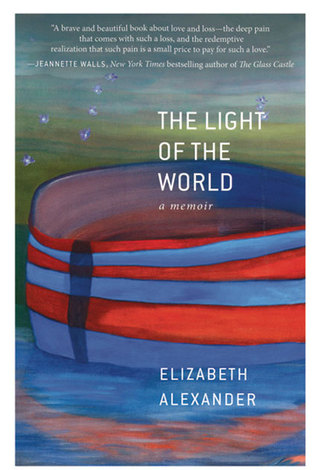

Arts & CultureElegy for a husbandElizabeth Alexander ’84 mourns and remembers, in beautiful prose. Sylvia Brownrigg ’86 is the author of six books of fiction, most recently a novel for middle-grade readers called Kepler’s Dream, published under the name Juliet Bell and now being turned into a feature film.  View full imageIn January 2009 Elizabeth Alexander delivered her stirring “Praise Song for the Day” at Barack Obama’s inauguration. It is a poem vibrant with Alexander’s distinctive sense of history—a recognition of the struggle and dignity of the civil rights movement that helped lead to that seminal American moment— and also a powerful call to optimism. “What if the mightiest word is love?” Alexander challenges. “On the brink, on the brim, on the cusp, / praise song for walking forward in that light.” There is light too in the title of Alexander’s powerful new memoir, and there is optimism of a kind; but both are filtered through profound grief. For The Light of the World is the heartbreaking story of a loss of light: the sudden death, days after his 50th birthday, of Alexander’s beloved husband, painter and chef Ficre Ghebreyesus ’02MFA. Joan Didion, whose book about her husband’s death set the bar high for such grief memoirs, tells of the irresistible urge to recreate the scene before a catastrophe. (She writes: “Life changes in the instant. The ordinary instant.”) So it is with Alexander’s account. After avowing that her narrative “is not a tragedy but rather a love story,” the poet goes over in close, colorful detail the days of work and family life that led up to Ficre’s abrupt collapse one spring evening in the basement of their house in Hamden, Connecticut, by the exercise treadmill, where he was discovered by their 12-year-old son. “What does it mean to grieve in the absence of religious culture?” Alexander asks, and the book is in large part her answer to that quandary, her attempt to make sense of what has happened to her. “I write to fix him in place, to pass time in his company, to make sure I remember, even though I know I will never forget.” She seeks, of course, the medical explanation for his death—though he was a trim, active, and apparently healthy man, Ficre’s arteries were blocked, she learns, “nearly completely,” so that he probably died instantly—though beyond that also some way of measuring, comprehending, her loss. In fluid, often lyrical prose the poet draws a loving portrait of Ficre, who left Eritrea at age 16, a refugee who lived in Sudan and Europe and finally the United States, where he eventually settled in New Haven. She offers the romantic touchstones of the couple’s courtship, and takes us through the birth and raising of their two sons. From the book’s first pages it is clear that central to Alexander’s task of remembering and honoring Ficre will be the inclusion of food, friendship, and art—essential elements of their 15 years together. The couple met in 1996 at Caffé Adulis, the Eritrean restaurant Ghebreyesus ran for many years with his brothers in New Haven, and interwoven through the book are several of his recipes (a shrimp dish, the ingredients with which he made his Bolognese, a lentil and tomato curry), descriptions of feasts they cooked together over the years, mentions of dishes others make to comfort Elizabeth and their children in the terrible aftermath of his passing. Many of these short scenes involve friends and family the author takes time to name and briefly describe, peopling the book with former students, siblings, nieces and nephews, and other friends in geographies ranging from Brooklyn to southern France. The heart of the story, though, is New Haven, and though the university is mentioned only passingly, the city’s streets, the hospital, the Grove Street Cemetery, and other landmarks give the home Alexander describes a wonderful specificity. Owing to colonial history, Ficre’s third language was Italian (ahead of English, though after Tigrinya) and there are lovely moments of his bantering with Italian craftsmen or pizza makers in that language. Perhaps more than anything, Alexander is eager to champion her husband’s artwork. Though he chose not to show his work, it’s clear that Ghebreyesus was fantastically productive, and soon after they met (an encounter Alexander describes as an “actual coup de foudre, a bolt of lightning”) he took Elizabeth to his studio, a place crammed with paintings, prints, and drawings. With great devotion Alexander conveys physical details of a man with “the kindest eyes anyone has ever seen” and “chocolate in his voice, a depth, a bottom....He was beautiful, and utterly without vanity.” The notes in his voice of greeting, the lovers’ jokes they traded in the kitchen, the passion he brought to the garden—all are brought into her affectionate patchwork reconstruction, as are a few of Ficre’s writings, a poem written for one of their sons, an artist’s statement. If sometimes Alexander’s language becomes repetitive or less vivid, the reader understands. (Julian Barnes remarked, in a review of Joyce Carol Oates’s account of widowhood, “In some ways, autobiographical accounts of grief are unfalsifiable, and therefore unreviewable.”) The voice’s integrity in its mourning is unquestionable. So intent is Alexander’s gaze on Ficre and on the family they created together, however, that she offers little sense of her own work life, or of her husband’s response to her poetry, her scholarship—or, for that matter, to the presumably memorable occasion of the inauguration. This humility must be deliberate, and reads as an almost wifely modesty, yet it makes the account of their coupledom curiously imbalanced. We notice this when Alexander includes several pages of a lecture she delivered on African American art just a week after her husband’s passing. It is a rich, authoritative piece of writing on the necessity of creating art in the shadow of loss. “And so the black artist in some way, spoken or not, contends with death, races against it, writes amongst its ghosts who we call ancestors.” She describes the students after the lecture lining up to shake her hand, or embrace her, in consolation. At the close of that lecture, we find Alexander once again reaching for the light: “Survivors stand startled in the glaring light of loss, but bear witness.” This book is Alexander’s own powerful witness to the love, and the man, she lost.

The comment period has expired.

|

|