loading

loading

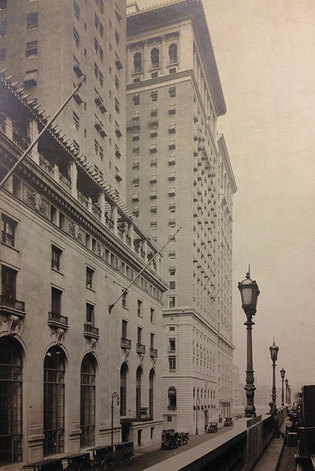

Old YaleThe “skyscraper club” turns 100Before he rebuilt Yale, James Gamble Rogers built the Yale Club of New York City. Judith Ann Schiff is chief research archivist at the Yale University Library.  Roger Bradbury Whitman/Manuscripts and ArchivesIn this 1914 view up Vanderbilt Avenue in New York City, the exterior of the newly built Yale Club (center) is visible top to bottom. View full imageBy the early summer of 1915, the new quarters of the Yale Club of New York City were move-in ready. Minutely planned by the building committee and the architect James Gamble Rogers ’89 over five months of weekly meetings, the neoclassical skyscraper with Italianate features combined elegance and comfort in what was then the largest clubhouse in the world. Some 3,250 members were eager to celebrate the opening in its great halls on Vanderbilt Avenue, but—this being in the days before air conditioning— they prudently waited until November. The club had been organized in 1897 (as the successor of an alumni association formed in 1868). In 1901 it had opened an 11-story clubhouse on West 44th Street, but after just a decade, that building felt too small. The decision was made to move east, to up-and-coming “Terminal City”—the Grand Central Terminal area—and construct new quarters over the rail yards. That new building is now 100 years old. As David McCullough ’55 writes in the club’s recently published history, subtitled A Century at 50 Vanderbilt Avenue, the interior “strongly evoke[s] Yale itself, and not by happenstance. It is the creation of James Gamble Rogers,...the architect of so much that is outstanding about the Yale campus.” But as it happens, the Yale Club came first: it was designed before Rogers presented his plans for Harkness Tower and the Memorial Quadrangle (now Branford and Saybrook Colleges) in 1917. In a New York Times interview about the Vanderbilt Avenue building—the headline was “Yale’s New Skyscraper Club”—Rogers said the aim was “that it should not be merely a social center for New York men, but that it should be made attractive to Yale men of all ages and from all parts of the country.” The first six floors included the public rooms, gymnasium, and library; the seventh to seventeenth housed the hotel rooms; and the top five floors featured dining rooms, ballrooms, and an outdoor terrace in terra cotta. The major construction challenge was to ensure stability over the two stories of railway tracks running under the building. The columns supporting the club had to be placed so as not to encroach on the clearance required for trains, and, to prevent vibrations, they had to run all the way down to bedrock without joining the railroad columns. The cost of the building was $1.25 million. Due to cost constraints, Rogers told the Times, “we eschewed extravagant materials and confined ourselves to using lasting and substantial materials and using them as well as possible”—for example, by using tile instead of marble in the swimming pool: “not skimping on structural excellence, but...making no effort to use rare, or pretentious materials.” The Rogers Papers in the Yale Manuscripts and Archives include hundreds of pages of detailed specifications for lavatories, fireproofing, ornamental terra cotta, china (including oyster plates, egg cups, and mustard pots), service bars, beer stations, and two large humidor rooms with a total capacity of 20,000 cigars. Rogers would become Consulting Architect of Yale in 1920 and Architect for the General Plan of Yale in 1924. He would design the first residential colleges and Sterling Memorial Library. He worked in a wide variety of styles: in Yale and New Haven alone he used Gothic, Georgian, art deco, and neoclassical. After his death in 1947, the New York Herald Tribune celebrated his eclectic achievements: “The styles of his buildings he changed as easily as his hats. His period was, we now see more clearly, an extravaganza of different styles.” What remained constant was his attention to the comfort of the buildings’ users. As David McCullough puts it in the club’s history, “you feel you are in a congenial, hospitable place, human in scale. You feel at home, that you belong.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|