loading

loading

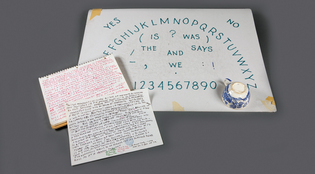

Arts & CultureObject lessonPoetry via Ouija Langdon Hammer ’80, ’89PhD, is a professor of English at Yale. He is the author of James Merrill: Life and Art, a forthcoming biography of Merrill.  Beinecke LibraryJames Merrill’s homemade Ouija board, which he used in writing poetry, is in the collections of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Shown with the board and the tea cup Merrill used as a pointer are transcripts from the board that he used to write his epic poem The Changing Light at Sandover. View full image

James Merrill (1926–95) was an American poet celebrated for his refined lyric gift and skeptical moral intelligence. But he was also another type of poet entirely: a strange visionary who renewed poetry’s ancient task of invoking sacred speech, in his case by the unlikely, faintly scandalous means of the Ouija board. The Ouija board is a popular entertainment and a kind of writing machine. It requires two or more people to place their fingers on a planchette or pointer, which then moves about the board indicating letters that spell out messages from the spirit world. Merrill received a store-bought board as a birthday gift from a friend in 1953. As a lark, he tried the board with David Jackson, a fiction writer he had just met, and it was an immediate success. So was his relationship with Jackson, who would be his companion in daily life and on the Ouija board for the next 40 years. For the first 20 years of their collaboration, JM and DJ—as they were known to the spirits—treated the board as a peculiar evening diversion, to be shared with friends after dinner over wine or a joint. They made their own board, to which they added numbers and punctuation, and they used a tea cup as a pointer. With this apparatus, they chatted at ease with dead friends and famous literary figures such as Wallace Stevens. Their familiar spirit, Ephraim, a Greek Jew from the court of the Roman emperor Tiberius, explained to them an elaborate system of reincarnation. Did Merrill believe what the spirits told him? He liked to answer, “Yes and no,” using words written on the board itself. He published a long poem in 1976 about these spirit conversations, called “The Book of Ephraim.” Then the tenor of the communications changed. Weird new speakers gripped the cup and began to unfold a cosmological story of creation and fall, urgently demanding that Merrill write new poems warning readers of the threat of nuclear destruction. The result was a 560-page poem called The Changing Light at Sandover (1982), a postmodern Dantesque trilogy in which Merrill transcribes messages from subatomic particles, “God Biology,” and other assorted characters and creatures, including a hornless unicorn known as “Uni.” Merrill and Jackson’s homemade Ouija board and the dime store tea cup they used as a pointer—glued together after more than one occasion when the spirits pushed it off the table in a pique—are kept in Yale’s Collection of American Literature at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. These unusual tools of one writer’s rather mad compositional method were a gift to the library from J. D. McClatchy ’74PhD, adjunct professor of English at Yale, editor of the Yale Review, and one of Merrill’s two literary executors. With his left hand on the cup, Merrill used his right to record letters, sorting the lexical lava into words and sentences. One of the transcripts pictured here recounts the destruction of a world before ours in a nuclear explosion. It is inscribed to “dearest Sandy”—McClatchy’s nickname—by DJ and JM, who call it “a page saved from the pyre.” The “pyre” refers not to a primeval apocalypse, but to Merrill’s choice to burn the Ouija transcripts he used to write Sandover. The pages shown here made it to the Beinecke, however, safe with the board and cup.

The comment period has expired.

|

|