loading

loading

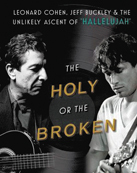

Arts & CultureThe song, not the singer“Hallelujah” is by Leonard Cohen. But multitudes own it. Marc Weidenbaum ’88 (Disquiet.com) is writing a book about the album Selected Ambient Works Volume II by Aphex Twin for Bloomsbury’s 33 1/3 series.  View full imageIt is the song that preteen fans of Shrek practice for recitals. It is the song that cable TV employs as the solemn score to montages of national tragedy. It is the song that has become core repertoire for dramatic competitors on prime-time singing shows. The song appeared in not one but two seasons of the self-consciously trashy teen melodrama The O.C.; in the film version of the graphic novel Watchmen, superheroes made love to it while apocalypse loomed. And now it’s the subject of a book by Alan Light ’88, The Holy or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley, and the Unlikely Ascent of “Hallelujah” To describe the song as “Leonard Cohen’s ‘Hallelujah’” would be factually accurate, but misleading, as Light explains. Leonard wrote it and recorded its first version, in 1984, but it was Buckley’s adoption of “Hallelujah” a decade later, on his album Grace, that took what was then a subculture also-ran, and put it on the path to global ubiquity. Today, “Hallelujah” is covered and employed in film and television with such frequency that Light quotes several individuals—including Cohen—who suggest that perhaps a moratorium is in order. While the variety of renditions and placements of “Hallelujah” seems eclectic, even perplexingly contradictory, Light points out that those contradictions are inherent in the song. Cohen’s originally recorded version opens with a biblical anecdote before proceeding to a music lesson and domestic sadomasochism. Cohen later altered verses, and they have been mixed and matched by subsequent interpreters to emphasize the spiritual and the profane, the ecstatic and the uneasy, the universal and the evangelical. Light takes us along the song’s path with the best sort of pop-music scholarship: obsessive, impassioned, and refreshingly agnostic about matters of genre. Light himself is a veteran music journalist, and one of his first books, a study of the rap group the Beastie Boys, grew out of work he did while a Yale undergraduate. His subsequent roles, as editor-in-chief of both Vibe and Spin magazines, as well as director of programming for public TV’s Live from the Artists Den, inform his interviews with an astonishing range of musicians. There are not many books that include first-hand conversations with musical artists as diverse as power balladeer Jon Bon Jovi, rakish chanteur Rufus Wainwright, Michael McDonald of the Doobie Brothers (1970s radio icons), and alt-cabaret firebrand Amanda Palmer. And that’s just a start on the list of musicians whose takes on “Hallelujah” flesh out the book’s narrative. In the process, Light proves himself one of a rare breed: a trainspotter who can spin a yarn. “Hallelujah” had an ignominious beginning, on an underappreciated Leonard Cohen album. Cohen’s sprechstimme style and mix of mystic and sexual yearning had made him one of the most celebrated songwriters of the rock generation, but that apparently wasn’t enough for the executives of his hit-minded record company, Columbia. They canceled the 1984 release. (A smaller label put it out two months later.) Then in the 1990s, the song’s rise to fame really gets going. Jeff Buckley puts out his heart-wrenching take, creating a core of “Hallelujah” fans. Just a few years later, he drowns in the Mississippi River at the age of only 30, and the song takes on the eerie aura of portent. Momentum builds in 2001, when “Hallelujah” is included in the massively popular animated film Shrek, thus entering the psyches of several generations of adolescents. Just a few months after Shrek’s debut, the twin towers fall in Manhattan, and VH1 adopts “Hallelujah” as the backdrop for a hastily produced 9/11 memorial video. It may be a tad premature to call “Hallelujah” “immortal,” as Light does, but that doesn’t mean the subject is unworthy of book-length study. Light makes his point convincingly: arguably, no contemporary song can touch “Hallelujah” for its ability to traverse not only genres and audiences, but also religious and political lines. (Light mentions in passing that “Hallelujah” is “a staple for college a cappella groups and glee clubs.”) If anything, this book could have been longer. Light’s take on the power of “Hallelujah” favors words above melody, couplets above chords. He interprets, with Talmudic (Bloomian?) intensity, the choices musicians make as to which verses they rearrange. But he devotes far less coverage to the backing arrangements. What of the timbre of a guitar, the relative density of an orchestration, a tonal reference between renditions, alterations in voicings, the use or lack of backup singers? Light mostly limits his discussion of the nonverbal to questions of genre and relative histrionics; we learn that Las Vegas drama queen Celine Dion, for example, is intriguingly calm in her interpretation. There are some welcome exceptions, notably the deeper musical probings of versions by Doobie Brother McDonald, Regina Spektor, and Justin Timberlake. Then again, fundamentally, this isn’t a book about music. It’s a book about culture. The various interpretations are the core of the story, but not the whole of it. Throughout, Light makes excellent use of anecdotes to tell his tale, including details about a musician who retraced Buckley’s final steps along the Mississippi and a story near the end of the book about the naming of a newborn child. If these stories don’t make you tear up, then you’re probably just not a member of the sizable “Hallelujah” chorus. Read the book anyway. Even students of the changing role of copyright in our post-Internet age will find much to learn from the song’s ascent. In Light’s informed opinion, it is precisely the absence of a singular, definitive, canonical recording that has left “Hallelujah” up for grabs, free for wide appropriation—and, thus, for profitable exploitation. It is good advice not to judge books by their covers, but as Light’s book shows: one might take the measure of a popular song by its covers.

The comment period has expired.

|

|