loading

loading

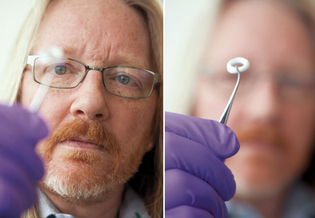

featuresInventions that will help save the world (if we let them)It doesn’t matter how useful it is, or how important. Sometimes, a great new technology doesn’t make it into the market or your life. Caitlin Kelly, author of Malled: My Unintentional Career in Retail, writes frequently for the New York Times.  Mark OstowMark Saltzman holds a prototype vaginal ring, for testing in animals, that is designed to protect against sexually transmitted diseases. View full imageIt seemed like a good idea at the time. In fact, it was an extraordinary idea: a new birth control method that would not only prevent conception but also protect women from sexually transmitted diseases like herpes, HPV, and even HIV. Beginning in 1989, Mark Saltzman, an engineer who uses nanotechnology to target drugs to specific areas in the body, was seeking a way to deliver contraceptives using an insertable vaginal ring. Nothing like it was on the market at the time. He envisioned a soft, flexible ring that could last three years, while it released antibodies—locally, with none of the systemic hormonal side effects of the Pill. It took Saltzman three years to develop a 10-milligram ring of nondegradable polymer to the point where it was ready for testing in mice. Then he hit the first major hurdle to commercialization. “We did the cost analysis,” he says, with a grimace and a sigh; it showed the antibodies were too expensive to produce. So, with the help of key collaborators, he cut the costs substantially by proposing to supply the antibodies not by cloning, but by culturing them in plants such as soybeans and corn. Since corn is a food and safe to use in the human body, the new approach looked promising. “We were going to change the world,” he says. “We had a nice team in place, ready to work together—plant biologists, reproductive biologists, engineers. Of all the things I’ve ever worked on, that was the one that most excited me, the notion that I could improve women’s health.” But the world was already changing, and not in his favor. Genetically modified food was becoming more prevalent in the 1990s, and so were US consumers’ concerns about its safety. In 2001, he recalls, “we started having trouble.” GMOs became a political hot potato, and pharma companies took notice. The project never happened. But Saltzman, the Goizueta Foundation Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Yale, hasn’t given up. A new contraceptive wasn’t that much in demand, he realized. “But novel microbicides? There’s still a lot of interest in that. There’s still a need for it.” He’s now readying a microbicidal vaginal ring for testing in other species. He also believes that nanoparticles that can be applied topically in a liquid form, to prevent HIV infection or herpes, are within reach. They’re on the list of products he’s trying to develop. What scientists initially envision in their offices and labs, and what products will eventually sell, in sufficient quantities at the right price to enough customers, are often remarkably different. No matter how many prestigious awards or grants they’ve won—Saltzman has been funded by the National Institutes of Health for 25 years—engineers’ creations may never make it into mass production.

|

|