loading

loading

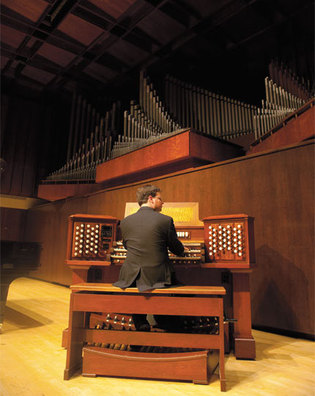

featuresThe radical virtuosoOrganist Paul Jacobs wants to change the way you spend your time. Matthew Guerrieri is the author of The First Four Notes: Beethoven’s Fifth and the Human Imagination (2012), a New Yorker Best Book of the Year. This article was made possible by the Seth E. Frank ’58LLB Literary Fund.  Mark OstowView full imagePaul Jacobs has a plan to save civilization. It is an idealistic plan. It is, perhaps, an impractical plan. And it is a subversive plan. As subversives go, Jacobs ’02MusM, ’03ArtA, is awfully soft-spoken and polite. His voice has a calming lilt. A conversation is punctuated with serene pauses as he assembles his thoughts into balanced sentences. At his favorite restaurant, he is on an affable, first-name basis with seemingly the entire staff. Around the halls of the Juilliard School, he offhandedly greets people around every corner with a similar familiarity. When, in 2004, he was made head of Juilliard’s organ department, he was one of the youngest department heads in the school’s history; even today, at the age of 37, he could, possibly, pass for an unusually contemplative student. And, yes: the organ—Jacobs is a virtuoso performer on an instrument practically synonymous with rectitude and sober learnedness. But make no mistake: Jacobs is a radical, his goal nothing less than a reconfiguration of society and its priorities. The plan? To hear Jacobs describe it, it’s simple. First: return the organ to classical-music prominence. Then: return classical music to cultural prominence. The rest will follow. In midwinter, Jacobs is just back from Carbondale, Illinois, where he played a recital in Southern Illinois University’s Shryock Auditorium. (The concert was dedicated to Marianne Webb, SIU’s longtime organ professor, who passed away in December; Webb had asked Jacobs some years ago to be the one to play her memorial concert.) The following Sunday he will be in Largo, Florida, for a recital at Prince of Peace Lutheran church. In season, it is a rare week that Jacobs is not concertizing somewhere across the country; like most evangelists, he spends a lot of time on the road. By any current classical-music standard, Jacobs is a star. He first became well known in 2000 for a series of Bach cycles: playing, from memory, the complete organ works of Johann Sebastian Bach—some 18 hours of music spread over 14 consecutive concerts—to mark the 250th anniversary of Bach’s death. (On the actual anniversary—July 28, 2000—Jacobs completed the entire cycle in a single day, playing from six in the morning until just past midnight.) He has performed similar concerts of the works of the incomparable twentieth-century French organist and composer Olivier Messiaen. “I work at it,” he says of such feats of memory. “Sometimes it comes easy, sometimes it’s difficult. But it’s so liberating in performance.” Jacobs’s recording of Messiaen’s final work for organ, the encyclopedic Livre du Saint-Sacrement, won him a Grammy in 2011, a first for a classical organist.  Mark OstowPaul Jacobs, ’02MusM, ’03ArtA, playing the organ at Juilliard. When he was made head of the organ department, in 2004, he was one of the youngest department heads in the school's history. View full imageJacobs’s playing is at once brilliant, philosophical, and painterly. You can particularly hear it in his registration, the way he chooses and mixes stops to create color. Alongside the organ’s customary vibrancy and horsepower, Jacobs will juxtapose combinations of unusual lucidity, the instrument’s sonic possibilities glimpsed like a clear, deep pool. He approaches the organ the way, say, Carl Sagan approached the universe: blissfully revealing its infinitude. Beyond Bach and Messiaen, Jacobs’s programs range far. “We have a wider span of music [to choose from] than almost any other instrument,” he marvels. He has expanded that list with a series of commissions and premieres. Last year, Jacobs played the first performances of Michael Daugherty’s (’87MusAD) The Gospel According to Sister Aimee—a grand, bombastic pageant for organ, brass, and percussion, inspired by the life of evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson—and Stephen Paulus’s Organ Concerto No. 4. A new concerto by Christopher Rouse is in the works. Both the collaborations and the new repertoire advance the first part of Jacobs’s plan: to reintroduce the organ into the well-grooved channels of classical performance. (Jacobs has his Juilliard students engage in similar cultivations, partnering with student composers to create new pieces, or putting together chamber-music performances with other instrumentalists.) Such projects can also remind audiences—and presenters—of a resource hiding in plain sight. In big cities, in particular, the organ can be an afterthought. Often, church pipe organs and organists are isolated from much of nonliturgical musical life; organs in concert halls have often been underutilized and neglected. When, in 2009, Lincoln Center reopened a renovated Alice Tully Hall before putting back the hall’s pipe organ, Jacobs was among those who went public with their worries that New York would be left without a major organ-equipped concert hall. After Lincoln Center found the money for a reinstallation, Jacobs inaugurated the restored instrument with a performance of Bach’s monumental Clavier-Übung III. (The tide continues to turn. In February, Jacobs played a recital in Washington, DC, on the Kennedy Center’s new 85-rank pipe organ, installed in 2012.) But outside large metropolitan areas, the organ can be the locus of a community’s cultural life. These instruments, the grandest statements of classical-music technology, still reside in churches, theaters, halls, across the landscape. Jacobs’s days on the road are not so much bringing culture to the masses as giving people the opportunity to reconnect with a culture that’s already there, and has always been there, in the places and spaces that are theirs. He recalls playing a recital to dedicate a new organ in the Roman Catholic cathedral in Helena, Montana. “The place was filled,” he says. “Over a thousand people came out to hear this concert.” His recital in Carbondale was the beneficiary of community efforts at publicity and promotion, and that hall, too, was full. Jacobs remembers, during his time at Yale, taking out ads in the Yale Daily News for his recitals, trying to drum up an audience. Sometimes it was even easier: when practicing in one of the campus’s chapels, he would leave the doors open, and students would wander in and, for a while, quietly sit and listen.  Harold ShapiroJacobs performs on the Newberry Memorial Organ at Woolsey Hall in the concert last October celebrating the inauguration of Yale president Peter Salovey ’86PhD. View full imageHis family wasn’t very musically inclined—but it was just musically inclined enough. “My grandfather would sometimes play a little something on the violin, or the accordion,” Jacobs remembers. “He wasn’t very good, but in some ways that was more encouraging—just seeing him make music for the love of it.” His grandparents also had a record collection, and Jacobs would lose himself in the classics. He started piano lessons at age five. He began to explore the pipe organ at a local Catholic church, the Parish of Immaculate Conception in Washington, Pennsylvania, at 11, when he was tall enough to reach the pedals. By the time he was 15, he took over as the church’s organist. (The parish has its own radical genealogy, being the one-time home of the famous Pittsburgh labor priest Charles Owen Rice.) Jacobs was admitted to Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music, studying organ and harpsichord. The institute’s single-minded focus on music laid the foundation for his indefatigable work habits. But Curtis’s narrow intensity also left him wanting wider intellectual exploration. Upon arriving at Yale, Jacobs purposefully sought out the brightest students outside the music department, only to find that they were even more outside the department than he expected. “They knew so much, about science, politics, art, literature,” he says. “But not about music.” A few had expanded their horizons as far back as the Beatles; next to none of them were conversant in classical music. Jacobs’s cause began to crystallize. He remembers going from college to college at Yale, sneaking into common rooms to eavesdrop on student debates. Jacobs was both awed by the erudition on display and occasionally uneasy at the ends to which it was sometimes put, knowledge pursued in the service of materialistic ends rather than for its own sake. His classmates at Curtis might have had more limited horizons, “but they had that fire,” he says, “that need to go after beauty for the sheer love of it.” At Juilliard, Jacobs encourages a recalibration of that balance between career and calling. The students are immersed in an atmosphere of short-term and worldly pressures: an emphasis on technique, a competition for jobs. The danger, in Jacobs’s view, is that, along the way, students lose sight of the ethical dimension of making music. “Musicians have a responsibility,” he insists, “a duty to their fellow human beings.” Talk with Jacobs long enough, and he will recommend a book: Leisure: The Basis of Culture, by the German Catholic philosopher Josef Pieper. A devotee of Thomas Aquinas, Pieper tried to draw wisdom from that tradition that might be applicable to the modern condition. Writing just after World War II, Pieper was dismayed by both capitalism and communism, systems that reduced human beings to agents of economic production; by “the world of planned diligence and ‘total labor’”; by a society in which even contemplation and reflection were reclassified as “intellectual work.” Against that whole apparatus, Pieper proclaimed a strikingly broad definition of leisure: “not a Sunday afternoon idyll,” he insisted, “but the preserve of freedom, of education and culture, and of that undiminished humanity which views the world as a whole.” Pieper’s analysis reached back to the cultus, the ancient societal patterns of worship and sacrifice—literally the “care” that was owed the divine. “Culture depends for its very existence on leisure,” Pieper wrote, “and leisure, in its turn, is not possible unless it has a durable and consequently living link with the cultus, with divine worship.” This is the duty that Jacobs talks about: reconnecting the listener with something transcendent, a vision of human existence well beyond the merely utilitarian, or even the readily comprehensible. It is a goal that classical music, in particular, long and explicitly pursued. But it is also a goal that, since the late nineteenth century, the prevailing culture has increasingly forestalled—by design, maybe. Because it is a goal at odds with the driving force in modern life: consumption. Our society of buying and selling, getting and having, has, in Jacobs’s estimation, sidelined what once was at the core of human identity: “We ignore the spiritual dimension of life.” But the organ, in his description, is a preserved bastion of the spiritual, for centuries at the hub of collective spiritual life, the vehicle for some of the most elaborate and monumental musical expressions of spiritual experience. That experience, for instance, is at the heart of Jacobs’s connection with Messiaen and his hedonistic sense of the spiritual, whom Jacobs describes almost as a fellow recusant: “an anomaly in twentieth-century music—a composer who was profoundly joyous.” Jacobs’s vision of classical music and its chance of transcendence returned to the center of cultural expectation goes against every consumerist trend of modern life. It is not just unfashionable; it is, in many ways, incompatible with the framework of a society that has been so pervasively reoriented around self-fulfillment and immediate gratification. But in that incompatibility is power, the power of an experience that at once reignites the possibility of an existence beyond current, limiting categories of politics and religion and entertainment. Jacobs thinks of the common ground—and common yearning—in seemingly contradictory schools of thought: “Nietzsche stared into the abyss, saints stare into the infinite,” he remarks, “but they’re both staring.” He thinks of those Yale students, full of knowledge, but wandering into his practice sessions, looking for something else. He thinks of the crowds in Carbondale, Illinois, or Helena, Montana, crowds not conversant, perhaps, in the academic language of music and its history, but “sophisticated in the way they listen,” Jacobs says. “There’s this real hunger for that experience, these encounters.” Paul Jacobs has a plan. It is an idealistic plan. It is, perhaps, an impractical plan. It is a subversive plan. And it is going to save civilization.

|

|

2 comments

-

Dr. Anonymous, 10:41am June 05 2014 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Daniel F. Case, 6:00pm July 30 2014 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.Matthew Guerrieri and Paul Jacobs both deserve a lot of credit for this highly civilized article about a supremely civilized artist. They are both testaments to the potentials of a remarkable species that astounds nature with its capacity for the extremes of grandeur and disappointment.

The more classical music can do to lift us above our present materialistic level, the better. Many thanks to Jacobs and Guerrieri.