loading

loading

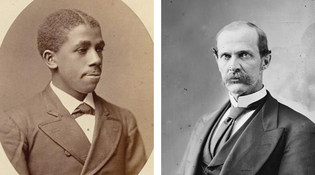

featuresWhat do we mean by “first”?The lives of two graduates raise questions about racial definitions. Mark Alden Branch ’86 is executive editor of the Yale Alumni Magazine.  Bouchet: Manuscripts and Archives; Gibson: Library of CongressEdward Bouchet (left) of the Class of 1874 was clearly perceived as African American before, during, and after his time at Yale. The stories of Richard Green and Moses Simons are less clear. Randall Lee Gibson, Class of 1853, a Confederate army officer and later US senator, had a black great-grandfather. View full imageWithin days of reporting on our website (yalealumnimagazine.com) about the discovery that Richard Henry Green might have been Yale’s first African American student, we were reminded by readers of two other men with arguable claims on that title. Their stories, like Green’s, remind us how complicated, fluid, and indeed arbitrary racial labels can be, and raise questions about just what we want to commemorate when we identify a racial “first.” The man long thought to be the first, Edward Bouchet of the Class of 1874, was clearly identified as African American throughout his life. The son of a former slave, he was educated in a “colored” school in New Haven before going to the Hopkins School (where he graduated first in his class) and Yale. Although he was only the sixth American of any race to earn a PhD in physics, he was unable to secure a long-term university position—very likely because of discrimination—and spent his career as a high school teacher and administrator. He remains a significant figure in Yale and US history as the first African American to earn a PhD from a US university. We know less about how Richard Green’s racial identity was perceived at Yale, or how it was perceived later in his life. Even more complex, though, is the story of Moses Simons, Class of 1809. Simons has already been identified as Yale’s first Jewish graduate (by Dan Oren ’79, ’84MD, in his book Joining the Club: A History of Jews and Yale). But evidence uncovered recently by two scholars—Adam Wolkoff of Rutgers and Laura Copland of Eugene Lang College—suggests that Simons could have had an African American mother, and that he was viewed by others as “colored,” in the parlance of the time. Simons came from South Carolina, apparently the son of one of five Jewish brothers who emigrated there from London. Records are not clear as to which of the brothers was his father, and no record of his mother has been found. At least one of the brothers is known to have fathered a mixed-race child. Simons became a lawyer in New York City. The only hints that he had African American ancestry come from an account of a criminal trial in 1818 after Simons was charged with assault. As told by a lawyer and journalist named Daniel Rogers in a contemporary legal periodical, Simons and his brother were asked to leave a dance because other patrons were uncomfortable with the presence of the “two coloured men.” Simons returned another night, and when he was refused entrance, he slapped the French dance instructor who was hosting the event. Testimony cited by Rogers supports the idea that Simons was perceived as a person of color. An acquaintance in Albany, for example, said there was no prejudice against Simons there except “on account of his complexion.” Rogers left no doubt about how he perceived Simons’s race: in a lengthy editorial appended to his account of the trial, he warned against letting “the African tinge mantle on the cheeks of our descendants.” Simons moved to London not long after the trial and died in 1822. Wolkoff and Copland suggest that in the legal community, Simons’s apparent color may have been ignored by colleagues until the trial forced the issue. There is no evidence of how Simons was perceived at Yale, but perhaps there was a similar reticence about the matter there. If the ambiguities and unknowns of Simons’s story make him a problematic candidate to be considered Yale’s first African American student, Randall Lee Gibson’s story threatens to make a mockery of the entire question. Gibson, a graduate in the Class of 1853, grew up on a sugar plantation in Louisiana, the descendant of a family of wealthy planters and slave owners. He was a colonel in the Confederate army, fought to defend slavery, and called black people “the most degraded of all the races of men.’’ He became a US senator from Louisiana after Reconstruction. But as Vanderbilt law professor Daniel Sharfstein ’00JD details in his book The Invisible Line: Three American Families and the Secret Journey from Black to White, Gibson’s great-grandfather Gideon Gibson came to South Carolina in the 1730s as a “free man of color” with a white wife. By Randall Gibson’s time, the family explained any dark complexion in the family as due to Gypsy or Portuguese roots, Sharfstein says. So where does that leave us? Could Simons conceivably have been the first African American to matriculate at Yale University? Surely Randall Lee Gibson was not, in any sense except the most limited. Perhaps we should simply continue to celebrate the people of color who broke barriers. And, in discussing Richard Henry Green’s status as the first African American student at Yale, we should remember that—like so much about the history of race in America—it’s complicated.

The comment period has expired.

|

|