loading

loading

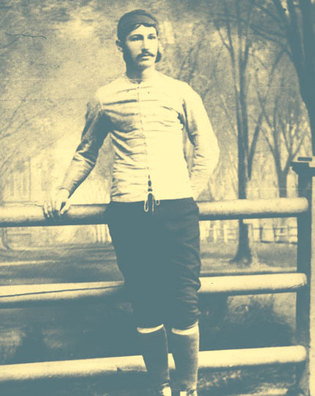

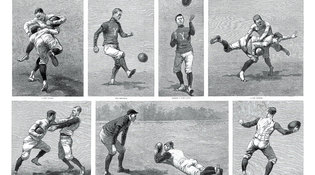

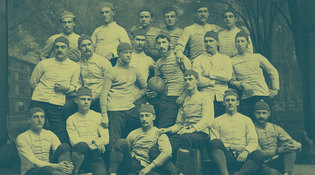

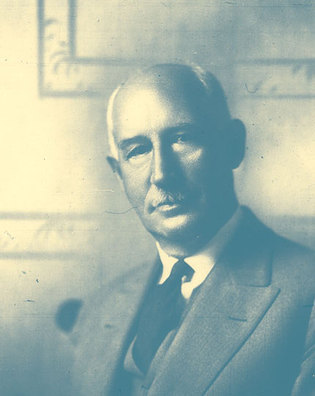

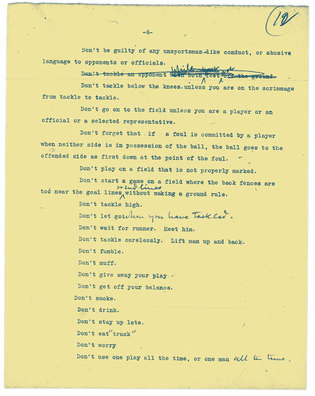

featuresAll AmericanBefore he had even graduated from Yale, Walter Camp took the lead in transforming a chaotic variant of English rugby into football as we know it. Julie Des Jardins is a professor of history at Baruch College specializing in the history of gender in America. This article is excerpted from her book Walter Camp: Football and the Modern Man with permission from Oxford University Press, Inc. Copyright © 2015 by Oxford University Press. Walter Camp will publish on October 1 and is available now for pre-order.  Manuscripts and ArchivesView full imageEven before Walter Camp joined the Yale freshman squad in 1876, football captain Eugene Baker ’77 could see that he was a powerful runner in spurts. He was instinctually a deceptive dodger, a skilled distance punter, and an able drop- and placekicker who soon mastered a straight-arm technique to ward off tacklers. Baker recruited him and one other freshman for the varsity squad, and Camp showed “sand” in his first big game, hitting a Columbia opponent so hard that the man’s head struck the frozen ground, leaving him lifeless on the field. As Camp stood over the bleeding scalp, he later recalled, he “was sure that the man’s head had broken open like an egg-shell.” He told Baker to take him out of the game, sickened by having inflicted his first concussion. As a freshman, Camp stood 5' 10''; he was skinny, not yet the 160 pounds he bulked up to by his senior year. His fresh-faced visage belied his physical force. At the Harvard varsity match that year, the opposing captain pointed to him on the sideline and warned Baker not to let “the child” play. Baker laughed, assuring him that Camp was “all spirit and whipcord.” Once the game commenced, a bigger, bearded man tried to exploit the seeming mismatch. He bore down on Camp when he did not have the ball, but the freshman responded by throwing his opponent to the ground and pinning his shoulders until the man flailed helplessly under his knees. Only later did Camp come clean about the fact that he had been clocked squarely under the chin in an earlier play. Although he wondered if his neck was broken, he held on to his man all the same. Camp was no bruiser by today’s standards or even then, but his effectiveness was less about size than determination. He described his survivalist instinct as a heavy dose of pluck coupled with an internal sense of honorable play that told him never to start fights, but to end them with definitive force. He was willing to experiment and improve upon his attempts; though it was a controversial play at the time, he made the first forward pass on record. Teammate F. R. Vernon ’81 recalled that Camp had sharp, unreadable eyes, which seemed to see as well in every direction without much movement of his head. He was “quick on his legs and with his arms. His action was easy all over and seemed to be in thorough control.” Sensing developments before they occurred, he was serene carrying the ball in his signature hand-satchel grip, zigzagging around men or warding them off with his free arm. Because he carried a ball with him to class, he had come to know every inch of its surface, juggling it in order to learn how not to fumble it. He transferred it easily from side to side while he ran, never losing it to opponents. “The ball seemed to stick to his palm, like an iron to a magnet,” Vernon marveled. In an era before the advent of helmets or protective gear, Camp played football with abandon. He took jabs and gave them. No matter how badly he was trampled, he willed himself back up on his feet. It is remarkable that an 18-year-old saw enough character-building potential in football to stick with it, given how badly he suffered its early ambiguities. In his first two years of playing, four of his scores were nullified due to confusion about the rules. In the Princeton game of 1877, he had hashed his way through opponents for 80- and 50-yard touchdowns, only to see both field-goal kicks missed and no scores result. The Intercollegiate Conference decided to alter the English rules and allow touchdowns to count as scores, but four were needed to equal one goal. The following year, in a game against Harvard, he kicked a goal 35 yards over the crossbar, only for the official to blow his whistle with the ball in mid-flight. The goal did not count, nor did it a year later, when he kicked the ball 45 yards against Harvard and saw the goal nullified by a holding call. In a game against Columbia at the cricket grounds in Hoboken, he came up from a play so badly mauled that his pants were in tatters. The referee called time, as teammates circled him and he walked off the field in a state of undress. When he returned, men came to blows over the calls. Despite cheap shots to his stomach, he was responsible for the game’s only goals. The free-for-alls did not deter him. Teammates remember Camp the next day with notebook in hand, dreaming up formations and game plans best suited to the rules as they (ambiguously) stood. In his quest for perfect play, he made defenders wear sealskin gloves so that in the cold their fingers had enough feeling to grab hold of ball carriers charging through the line.  Courtesy HarpweekArtist Frederic Remington ’00MFA played football with Camp in 1879. Remington soon dropped out of Yale, but football was a regular subject of his work, as seen in a series of illustrations of a Yale practice he did for Harper’s in 1888. View full image Manuscripts and ArchivesIn his senior year, Camp served as captain of the 1879 Yale team, which went undefeated. View full imageCamp was not a “trained leader,” as one teammate explained. He was an “undisputed” one. As a natural mentor, he had the ability to motivate teammates, so they made him team captain in 1878. He took the job more seriously than anyone before him, banning tobacco during the season, as well as any fraternizing past 11 o’clock the week of the Princeton game. Looking back, his was also the first modern training regimen on record. Everyone complied with his rules but Johnny Moorhead ’80, a talented runner, whose curfew-breaking caused his captain to summon a meeting in the dorm. As a matter of principle, Camp threatened to resign as captain if Moorhead did not quit the team. The move seems drastic, but it had the desired effect of galvanizing the men. Moorhead offered to quit if it meant that Camp would stay. (Moorhead eventually was reinstated.) Camp’s teammates never forgot the incident; it set the tone for the kind of discipline for which Yale men were famous for the next 30 years. In the nights before games, players assembled on Camp’s dorm room floor, backs to the wall, nothing in the center of the room but a football and their captain mapping out strategy. He spoke, but he listened more; he had a knack for sifting through points of view and incorporating them into a singular plan of attack. Teammates thought him intense, but eminently democratic, as “class feeling” gave way to “Yale spirit.” No one yet knew he was acting like a prototypical coach. In time, the drillers of men would come to be known as “advisers” and “coachers,” but a coach as known today did not yet exist. As captain, Camp was a player, trainer, and adviser all in one. From the beginning, Eugene Baker had recognized Camp’s leadership and involved his young protégé in the governing facets of football, bringing him to the annual convention of the Intercollegiate Football Association (IFA) in 1877. This body of Princeton, Harvard, Yale, and Columbia men met on neutral ground, the Massasoit House in Springfield, to hammer out a daunting number of technicalities. The playing fields at various locales, for one, had different dimensions; some even had clotheslines as field goal crossbars. As yet, there was no consensus on how to handle injuries or the substitution of players; it was not unusual for men to endure two and a half hours of continuous play before leaving the field. Players had no dressing rooms, trainers, or regulation uniforms. Instead of helmets, they wore knitted caps or nothing on their heads. Initially, in 1876, IFA regulators had established the dimensions of the standard leather ball and playing field and agreed to 61 rules that largely conformed to those of English rugby. They also agreed to hold a season-ending championship game—placing a premium on crowning a winner even in the early days. Arguments nearly caused the IFA to go defunct before it got off the ground, however. Yale and Columbia protested the meeting in 1877 because of disputes about scoring procedures and how many men should be allowed on the field. As captain, Camp attended the following year, convinced that it was in Yale’s best interest to have a hand in shaping the rules to its strengths. Yale men wanted touchdowns to be scored differently, and the number of men on each side to be reduced from 15 to 11. With fewer men on the field, Camp figured that speedier players like him would have fewer obstacles to run through, and as a strategist, he could more easily map out plays. Fewer players also made the transport of the team to and from games more affordable. But his proposals were rejected. Camp was not deterred. He proposed 11-player teams the following year—and the year after that. Yale refused formal membership in the IFA until his terms were accepted, and they finally were in 1880. At this stage, Camp was the elder statesman of the group, and the contours of his larger plan were coming into view. He envisioned a game played by a more physically tuned variation of the gentleman athlete, as equally decorous as his British counterpart, but more virile because he had more poundage and physical force. And thus he saw less need for the union rules handed down from across the Atlantic. Blocks and tackles below the waist, for instance, need not remain illegal in his physical game. He proposed counting “safeties,” defensive scores that did not exist in rugby, and to make the field’s dimensions 200 by 400 feet to heighten the competitive drama. Most radical of all, in October 1880, he proposed a total reorganization of men on the field, discarding the English formation of the scrum for an American line of scrimmage.  Manuscripts and ArchivesFor years after his pioneering career as a football player, Camp (above, in a 1920s photo) influenced the sport through his position on the rules committee. View full imageCamp thought the English scrum was ineffective for establishing clear possession: the rugby official restarted play merely by tossing the ball into a tangle of interlocking players, and more times than not, pushing the ball forward meant relinquishing it to opponents. Sometimes scrums pushed the ball back and forth for minutes at a time, leaving spectators confused about what was going on underneath the bodies. Camp thought the scene too chaotic to be an indication of skill, and he encouraged his teammates to seek order by pushing the ball backward, not forward, with their heels to ensure that they did not relinquish the ball. Control was the key to his game, as it was to his sense of manhood. As players turned chancy scrum play into the skilled seizing of possession, they separated themselves from mere boys on the field. In Camp’s scrimmage, the opposing sides were more discernible, much as in the gentlemen’s wars of an earlier age. Players lined up and created a clear delineation of offense and defense, suggesting that from early on, Camp wanted his game to be accessible to spectators. By removing some of the seeming randomness of possession, Camp unwittingly created new facets of the game. There was now a need for a craftier tactician to premeditate plans of attack, for instance, and, to gain the edge, teams needed to practice with specialized purpose to work through all the tactical possibilities. Although he emphasized a team concept for the American game, the scrimmage allowed a field general to emerge: Camp called him the “quarterback” and decided he was more akin to a corporate manager than to a coach, delegating the ball to his employees. The quarterback would have the ability to move the ball laterally and pass it off to others, but not advance the ball on his own, not yet. But with him in position, the standard T-formation offense started to emerge: seven men at the line—linesmen (who stood up straight); the “snapback,” eventually known as the “center” for his position in the line; and men who flanked him, called “guards,” for their function to protect. In addition to the quarterback, the “fullback” and “halfbacks” positioned themselves behind the line. Although the formations of these players would shift any number of ways, from this point on their names largely stuck, as did the term “tackle” on the defensive side.  Manuscripts and ArchivesBeginning in 1883, he edited the annual guide to the game, including frequent rule changes in the early years. The Spalding guides also included Camp’s wide-ranging list of rules for players, as seen in this 1913 manuscript version (below). View full image Manuscripts and ArchivesView full imageNow the general structure of the game was in place, and Camp made minor adjustments as needed. There was, for instance, the modification he made after witnessing Princeton’s “block game” in 1881. Until then, there was no consistent mechanism in place for the transfer of possession when a team failed to make forward progress with the ball. Camp had figured that proper sportsmen would punt the ball away in due time, but Princeton men, unable to gain yards on their own, simply held the ball for the entire first half of the game against Yale, reasoning that if they could not score, they would not give their opponents a chance to either. Yale men responded in the second half by prolonging their possession of the ball too, until Camp punted the ball away. The scenario was tantamount to a baseball player swinging through or ignoring pitches over and over, regardless of the strike count. In 1882, vowing not to allow “the football rules to become a refuge for weaklings,” Camp invented the concept of “downs.” This was an innovation that kept pacing, as well as the spectator, in mind. The offense essentially would be given a limited number of tries or downs to make headway on the field. If it did not advance five yards or lose ten after three plays, it relinquished possession of the ball to the opposing side. To incentivize forward progress, Camp also proposed adding value to safeties, awarding points to defenders who pushed offenses back past their own goal line. All this was fine, his fellow rule-makers decided, but they warned that under the system of downs, it would be hard for officials and spectators to discern whether the ball holder made his five-yard gain to retain possession. Camp’s solution was to mark the field with cross lines spaced five yards apart, from sideline to sideline, so that one could gauge a man’s gained or lost distance with accuracy. Fellow rule-makers begged him for clarification: “Like a gridiron?” they asked. “Precisely,” he answered. But all was far from solved. At an 1883 rule meeting, it became clear that scoring procedures also needed to be overhauled: if only rule-makers could agree how. Initially, only goals counted as scores, with touchdowns gaining value over time. IFA members differed on how much value they should assign to them, their preferences depending ultimately on whether their teams’ kicking or running games were stronger. Safeties were also a contentious matter, given their common occurrence in early contests. Their value was ambiguous until Camp proposed a clearer scoring scheme that distanced American football from English rugby even further. By 1885, he convinced the committee to award six points to goals from touchdowns, five points for touchdowns without goals, three points for field goals, and two points for safeties—up from one point the previous year. He believed the numerical system would maintain the competitive tension for players and eliminate ambiguity for fans, creating sport and spectacle all at once. Still, ambiguity remained, partly because the official rules of college football, decided upon by a mere handful of men, changed radically from one year to the next and were not uniformly understood by the players. On December 5, 1883, the rules committee attempted to minimize confusion by authorizing Camp to copyright and print the changing rules in an annual guide to be made widely available to college men. As editor, Camp would come to be seen by the public as the official official of collegiate football. So began his 47-year career as a college football rule maker and editor. For 28 of those years, he served as secretary of the rules committee rather than as chair, perhaps to underplay his influence. But make no mistake: his views prevailed, especially in the early years. Although his presence on committees was never blustery, he got what he wanted with stealth and finesse. He had a reputation for solving problems and building consensus. When challenged, he diverted assaults and narrowed divides. He had a way of listening intently to all suggestions before someone invariably uttered, “Well, let us see what Walter thinks about it.” If he looked surprised, the proceedings had likely already unfolded in his mind like moves on a chessboard—or plays on a football field. More times than not, in the end, men found Camp’s suggestions most logical. He lulled them into acceptance of his power.

The comment period has expired.

|

|