Mark Alden Branch '86

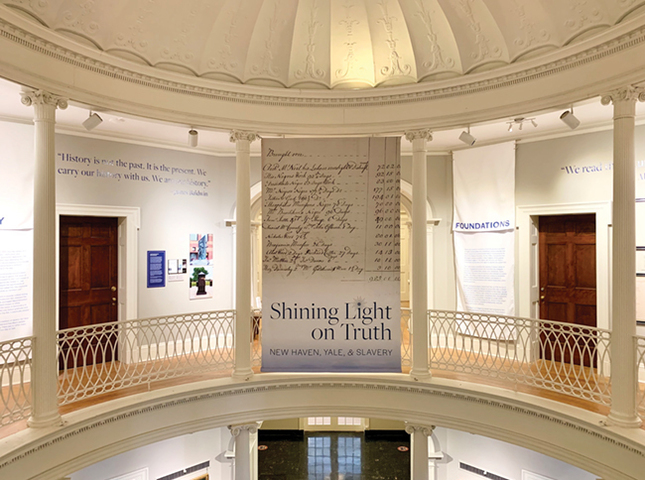

An exhibit at the New Haven Museum presents the findings of the Yale and Slavery Working Group.

View full image

Mark Alden Branch '86

An exhibit at the New Haven Museum presents the findings of the Yale and Slavery Working Group.

View full image

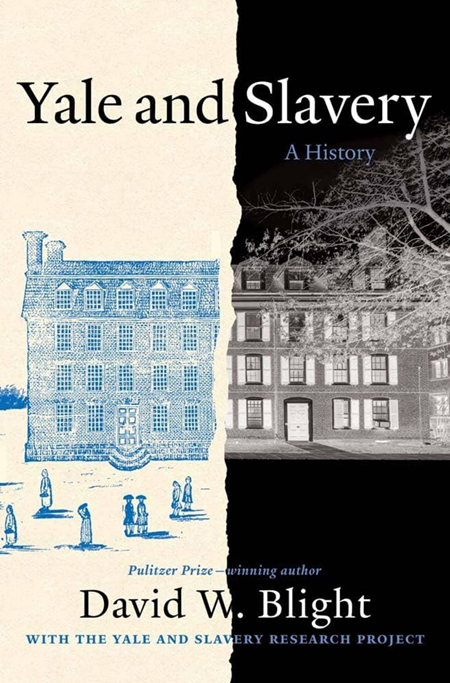

The project also produced a book that is for sale in print and available for free online in a digital version.

View full image

The project also produced a book that is for sale in print and available for free online in a digital version.

View full image

Until very recently, the name “Berkeley” made me think of beautiful trees, an underground tunnel, a building dissected into two halves, and my long-ago days with friends in Berkeley College. Those memories still make me smile. But by now, I’ve learned a great deal more.

The background: George Berkeley (1685–1753) was a brilliant thinker. He studied language, math, and philosophy at Trinity College, Dublin; was ordained in 1710; and eventually became the bishop of a small town called Cloyne, far south in Ireland. Berkeley is known for his work as a philosopher. The great poet Alexander Pope believed that Berkeley had “every virtue under Heaven.” Anne Forster Berkeley, his wife, declared that “Humility, tenderness, patience, generosity, charity to men’s souls and bodies, was the sole end of all his projects, and the business of his life.”

Yet Berkeley also bought and exploited humans.

In 1729, George and Anne sailed to Rhode Island. There they purchased a farm, along with at least three enslaved Black people, two men and a woman, to work on it. They were named Philip, Anthony, and Agnes. We don’t know whether those were their chosen names or whether the names were imposed on them. The farm spanned 96 acres, so there may have been other enslaved Black workers.

Berkeley gave his farm to Yale, as a funding source for the promotion of “Charity, Learning and Piety in this part of the World.” For decades, Yale earned money by renting Whitehall farm, due to the labors of several enslaved people working there.

Bishop Berkeley was one among thousands of white people all around the globe who, from the 1600s deep into the 1800s, captured, bought, sold, exploited, and abused Black people—as if they were merely possessions; as if they had no intelligence, no honor, no integrity, no love.

After hundreds of years of sweeping uncomfortable parts of their past under the carpet, many American universities have stepped up to learn whether they, too, had been profiting off the enslavement of human beings long ago. President Ruth Simmons of Brown was a key catalyst in 2003. In 2020, President Peter Salovey ’86PhD led Yale to join this essential work of reckoning fully with history. He formed the Yale and Slavery Working Group, chaired by Sterling Professor of History David W. Blight, and charged the group of faculty, staff, and community members to make a thorough assessment of Yale’s historical entanglements with slavery, the slave trade, and abolition—resulting in the book published in February. Many at Yale and beyond contributed to the work, looking through the archives, noting local memory, and drawing from generations of prior scholarship. Yale also issued an apology for the crimes of the past. It will donate funding to people learning to teach, if they spend three years teaching in New Haven public schools; it will add a teachers’ institute in 2025; and will soon invest more funding for HBCUs—historically Black colleges and universities.

The book, Yale and Slavery: A History, by Blight with work by Hope McGrath and Michael Morand ’87, ’93MDiv, and a foreword by Salovey, can be purchased in bookstores and is available online for free. I heartily recommend it. It’s critical that we understand the past, as there are resonances and aftermaths of the past that continue to shape and trouble our present.

Although we at the Yale Alumni Magazine weren’t involved with the work—and there was much, much, much work—we can share a few highlights (below) from others at Yale. In addition to the book, Yale has produced an audio walking tour, supported the exhibition Shining Light on Truth: New Haven, Yale, and Slavery at the New Haven Museum, and launched a website that both presents the research and documents the commitments Yale is making in response.

Below are some highlights from the book.

Chapter 4: Slavery and the American Revolution

It begins when the British invaded New Haven in 1779, but rather than discussing artillery and positioning, the chapter starts with a pregnant woman who is afraid. The woman, Sarah Lloyd Hillhouse— wife of James Hillhouse, Class of 1773—was fortunate: Jupiter Hammon, an enslaved Black man, was in the house and could protect her while her husband was away. Hammon was among the first Black writers published in America, beginning with his first work published in 1761. Later, he gave a speech to the African Society that included this poignant sentence: “If we should ever get to Heaven, we shall find nobody to reproach us for being Black, or for being slaves.’’

Another part of Chapter Four concerns Jonathan Edwards and his son. I still remember, from my college days, a phrase from the elder Edwards’s sermon: “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.’’ I knew he had workers who were enslaved. But until I began reading Yale and Slavery, I hadn’t known that Jonathan Edwards Jr. (1745–1801) had written and published, anonymously, a series of articles on slavery. It’s comforting to know that Edwards Jr. deviated sharply from his father’s view that “true virtue’’ included owning the enslaved. Although he didn't put his name to those articles, Edwards Jr., who was a pastor in New Haven for some 25 years, made it clear that he felt slavery was terrible.

Chapter 10: Black Students at Yale

This chapter starts off with a well-deserved putdown in the Connecticut Courant newspaper. It was 1871, and a politician was aghast that his son in Yale College had had to sit next to a Black student. The father quickly wrote to the professor who allowed that to happen, and demanded that his son sit somewhere else, “as it was for many reasons distasteful to sit so near a negro.’’ The professor, the Courant wrote, replied as follows:

At present the students were ranged in alphabetical order, and it was not in his power to grant the favor, but “next term the desired change will be brought about, for the scholarship then being the criterion, Mr. Bouchet will be in the first division, and your son in the fourth.’’

Edward Bouchet, Class of 1874, ’76PhD, was extra-ordinarily brilliant. Due to racism, he could never work as a professor. He was able to spend 26 years teaching chemistry and physics at a Quaker establishment—the Institute for Colored Youth—but left when the school changed to vocational training. He found some brief teaching positions in Virginia, Texas, and elsewhere, and he applied for a job at his alma mater in 1905. But Yale would not hire him. Bouchet came back to New Haven in 1916. He died in 1918. For years, there was no tombstone on his grave. Yale Professor Curtis Patton led the effort to finally place one, in 1998.

Interlude: Black Employees at Yale

Black men working as custodians in the nineteenth century were colloquially known as “sweeps.” They swept the dormitories, made students’ beds, and cleaned up buildings. Many were leaders in the Black churces and community organizations. But among Yalies, they were often the “focus of scorn, derision, and racist epithets.” Henry Beers, who graduated from the university in 1869 and became a professor of English at Yale, recounts a roommate’s racist repartee: “That blasted n----- woke me up, and it’s only a quarter of seven.’’ “Well, you left a notice for him to wake you, didn’t you?’’ “Yes; but I thought he couldn’t read.’’

Chapter 11: Embracing the White South

Yale’s 1901 bicentennial was huge. Almost five thousand people returned to revel with their friends and cheer their Alma Mater. Over 60 of them received honorary degrees. But there was a drawback: “Yale aspired to national greatness’’—which led the university to bring white Southerners back into the fold. Both Northerners and Southerners spoke, praising Yale, each in their own way.

In 1902, Black educator, John Wesley Manning, Class of 1881, gave a talk in New Haven. It described the disturbing trends of segregation accompanying national white reconciliation. He spoke of “Restrictions in accommodations, offensive remarks, an utter disregard of humanitarian considerations. . . . The North became as it were Southernized.’’

At the New Haven Museum, I saw names of those enslaved by trustees, donors, and presidents of Yale. There are New Haven ads from the 1750s to early 1800s, that say, for example: “TO BE SOLD, A likely Negro Wench, about 30 years old.’’ The displays convey the ubiquity of racial slavery at the foundations of Yale. Slavery, the exhibition notes, was present from the settling of New Haven and “did not end until 1848 in Connecticut, the last state in the region to abolish the system fully.’’ The persistence of slavery, along with laws against voting by Black men and other restrictions on Black liberty, led William Lloyd Garrison in 1835 to describe Connecticut as the “Georgia of New England.”

Today, in New Haven and the nation, there is a gap between the socioeconomic status of most white people and most Black people. We who are white and prosperous must reckon with our history. As Paul Simon sang: we have tended our own garden much too long.

loading

loading