loading

loading

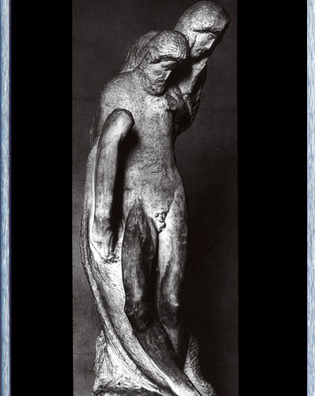

The patriarch Alinari/Art Resource, NYMichelangelo's last sculpture was a pieta, which the artist was still working on the very day he died. Scully sees in it an artist "using the crudest sculptural tools. He's trying to make it breathe. He's trying to breathe himself." View full imageFor the past 16 years, Scully and Catherine Lynn have spent most spring semesters at the University of Miami, where Plater-Zyberk is dean of the School of Architecture. Scully teaches modern architecture; Lynn teaches architectural preservation. They own a house in Coral Gables. He rows there on the canals, where the main hazard is that basking manatees will go sighing "thalasses, thalasses" beneath the keel. Apart from the effects of exercise, Duany attributes Scully's persistent vitality to Lynn. They met when she came to Yale as an art history graduate student in 1978, and they married in 1980. "He wouldn't be as alive, as exciting, without her. She is a colleague, not just a wife. They write together, and edit each other's articles." With the architectural critic Paul Goldberger ’72 and Erik Vogt ’99MEnvD, they co-authored a 2004 book, Yale in New Haven: Architecture and Urbanism. (It had originally been intended for Yale's Tercentennial celebration in 2001 but arrived late, and perhaps just as well, since it was characteristically not all that flattering.) In addition to the two endowed Yale professorships, Scully has been honored by the National Building Museum in Washington, DC, which in 1999 established the Vincent Scully Prize for achievement in architecture and urban design. (Recipients have included Jane Jacobs and Prince Charles.) In 2004, Scully received the National Medal of Arts, the nation's highest honor in the arts. (In the official photograph, he smiles wanly beside a beaming President George W. Bush ’68.) Scully tells a story about an honor that, though less formal, was plainly more thrilling. It's also, as it happens, a story about male rivalries, and marriage. In the mid-1990s, a 90th birthday party for Philip Johnson, the doyen of the architectural world, took place at the Four Seasons in New York. Jackie Onassis was greeting guests at the top of the stairs when the Scullys arrived with the architect Michael Graves. After they'd passed by, "Michael and I were like, Wo-o-o-o-o-w. She turns. Looks at you. She used to focus -- focus, that's what she'd do." Later, Scully and Lynn found themselves directed to the head table, where Onassis, who knew Scully's work, beckoned for him to sit beside her. Scully proceeded to entertain her through much of the party, on topics from architecture to a Kipling verse about a dog named "Monsieur Bouvier de Brie." Meanwhile, the guest of honor, neglected on Jackie's other side, "was getting madder and madder at me. She was talking to me all the time. She wasn't talking to Philip. So when it came time for Philip to take a bow he said, 'Now I want everybody in this room who's an architect to join me here. I don't want anybody who's not an architect. I don't want anybody whowrites about architecture. I want the architects.'" The memory of it makes Scully laugh. Later, on the walk home, when he was still hovering a foot or two above the pavement, it dawned on him that his wife might also, perhaps, be mad. But Lynn merely patted him on the forearm and said, in a tone of affectionate irony, "Don't worry, Vince. It would be un-American to resist Jackie Kennedy." "Ladies and gentlemen," Scully is saying, as the auditorium lights go dim. "I don't like last classes, this one least of all. I've been teaching at Yale for 61 years." Here his voice trembles, then gravels down into the sort of cough meant to conceal emotion. "But I've enjoyed this class more than any other. Part of that's due to you, and I owe you thanks for your attentiveness. The other reason I like this one most is that I feel for the first time in all those years I'm beginning to get it right." He gets a laugh, but also means it. "Sometimes they say the mathematician is brightest in his twenties, but that's not true for us," for humanists. "We slowly grow and then, just at the time when we think, 'Yes, we know,' then it's too late. It's too late for us, but not maybe for the next generation." The lecture is about Michelangelo and he begins with the way the artist, young as he was, could express the "real affection, real sorrow, real love" in his Pieta: the "wonderful, simple movement" of the mother's right knee hiking up and lifting the body, one arm reaching behind, the fingers pressing into the slack flesh of the rib cage, while the upraised palm of her other hand says, "This is my dead child." He moves on to Michelangelo's David, commissioned by the city fathers of Florence, and focuses on how the artist exaggerates the right arm, "the one that's going to do the business," clutching the stone with which to slay Goliath. The two sculptures, carved at almost the same time, depict, says Scully, the artist's two great loves, Christ and the Republic of Florence. "He cares about Florence. He cares for the fact that it is a republic. And when it falls under a Medici tyranny, his heart dissolves with sorrow." He moves to a side view of the David and points out the face, contorted with "doubt, irresolution," and "baser emotions -- fear, disgust, revulsion." Scully, a soldier once himself, shows how, from the side, David's body doesn't convey "any sense of young manhood stretched, young and tight and resolute. It's like a stalk, the head looks too big, and it's as if he's asking the fundamental sculptural question: Must you act? What have I got against the giant? What is this act that I must commit?" The lecture circles around, through Michelangelo's architecture, back to a final sculpture that the artist struggled with until the day of his death, at 89. The slide on the screen shows a half-formed work in which "this shaky-legged Christ is falling back in the arms of his mother," and the two of them seem to be "melting into each other, dying away at one time, into one flesh." The "wonderful dexterity" of the artist's youth has vanished, Scully says, and "now here at the very end he's using the crudest sculptural tools. He's trying to make it breathe. He's trying to breathe himself, I suppose. Everything about it has to do with death" -- of Christ, the Virgin, and the artist. But again Scully moves the audience around to the side, to see how the long, loose arm of Christ forms an arc, and the intractable stone seems to move with it "into pure spirit," and thus he leaves his students with an image not of death, but of art overcoming it to form "one great neoplatonic circle in the sky." The applause begins and Scully thanks his listeners two or three times. Then he does something no one in this class has seen thus far: instead of staying by the stage to speak with students and visitors, his usual practice, he steps away from the lectern and strides resolutely to the back of the room. People look around, as if to ask whether this is, after all, the end. But later, Scully explains that it's the way he finishes every semester, walking out of the room and back into the streets of New Haven. "You don't want to stand there like the royal family acknowledging applause. It's too disgusting." Leaving is simply the best way to make them stop clapping.

The comment period has expired.

|

|