loading

loading

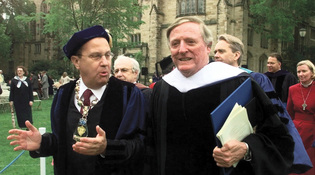

featuresWilliam F. Buckley: the ideologueAfter publication of God and Man at Yale, Buckley's broadside against his alma mater, Yale struggled to contain the fallout. Gaddis Smith ’54, ’61PhD, is the Larned Professor Emeritus of History. He is writing a history of Yale in the twentieth century.  AP imagesYale president Richard C. Levin, left, with Buckley on the day in 2000 when Buckley received his honorary degree. View full imageIn 2000, Yale awarded William F. Buckley Jr. ’50 an honorary degree. President Richard C. Levin, referring to Buckley's famous indictment of the university -- God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of "Academic Freedom," first published in 1951 and still very much in print -- said, "When you were at Yale, your sharp, youthful observations stirred controversy and challenged us to self-examination." In fact, the response at the time was less self-examination than fear, revulsion, and damage control. I was an undergraduate when the book appeared and knew, then or later, almost all of the people mentioned in the book; and I played a small part in preparing the response. What I have to say combines historical research and personal memory and opinion. The heart of God and Man at Yale is Buckley's assertion "that the duel between Christianity and atheism is the most important in the world [and] . . . that the struggle between individualism and collectivism is the same struggle reproduced on another level." He said that influential Yale faculty and the university itself were leading students to join the side of evil in both aspects of this struggle. The fate of the university and indeed of the nation was at stake. The solution was for the faculty to be required to inculcate belief in Christ and to explain the evil of "collectivism," defined as government restrictions on the economy. The orders should come ultimately from the alumni via the Corporation -- as the owners of Yale and employers of both the faculty and the administration. Academic freedom, in the ’50s as today, was a cherished concept in higher education, with origins early in the first universities in Europe, although it was not widely acknowledged in the United States until the twentieth century. For Buckley, it was hypocrisy and should be abolished. "Freedomites" (his word) were simply hiding their misconduct behind a false claim. Faculty should owe their positions not to academic freedom, but to alumni. To quote: Buckley did concede that there should be freedom in scientific research, with a distinction made between teachers and researchers who would work in institutes and not teach. There was no sense in the book of Yale as a research university. The campus and national circumstances in which Buckley wrote are important. He entered Yale in 1946 after serving in the army and was a close observer of the intensifying Cold War. As chairman (editor-in-chief) of the Yale Daily News throughout 1949 his outspoken editorials were both admired and despised. For example, in March 1949 he denounced sociology professor Raymond ("Jungle Jim") Kennedy ’28, teacher of a popular course, for dismissing religion as a matter of "ghosts, spirits, and emotion." A year later, Kennedy was murdered while doing research in Indonesia. He remained, however, Buckley's exhibit number one. In the winter of 1950, Buckley's last semester as an undergraduate, Senator Joseph McCarthy gave his name to a national campaign to find alleged Communists and their sympathizers and purge them from the government, universities, Hollywood, wherever they lurked. Buckley admired McCarthy and would write his second book on the man. Meanwhile, the very conservative Yale president Charles Seymour ’08, ’11PhD, was winning approval from the McCarthyites for pledging that there were not and never would be known Communists on the faculty, and from Buckley for having called on "all members of the faculty, as members of a thinking body, to recognize the tremendous validity and power of the teaching of Christ." Seymour acted on these beliefs when he negotiated a $500,000 endowment for the minuscule and unfunded American Studies program from the ultraconservative philanthropist William Robertson Coe. Seymour proposed that the expanded program carry this description: "The American Studies Program at Yale is designed to inculcate in our students an appreciation of the ideals fostered by our forefathers and exemplified by the development of free American institutions. It is designed as a positive and affirmative method of meeting the threat of Communism." The last sentence, said Seymour, is "the nut of the matter." Coe replied that the description should also refer to "State Socialism" -- the real threat, since the American people were not likely to accept Communism. Seymour, agreeing, expatiated on the viciousness of the New Deal. "The extension of Government aid and the consequent deterrent to individual initiative is not in accord with the American tradition. . . . This should be made clear in setting forth the program." Buckley himself could not have said it better. Seymour retired in June 1950, as Buckley was contemplating writing his book. The new president, a young history professor named A. Whitney Griswold ’29, ’33PhD, was appalled by Seymour's description of American Studies. He personally rewrote it, removing the taint of indoctrination, for the Course of Study Bulletin. As American setbacks in the Korean War stimulated McCarthyism's hunt for subversives, Griswold became a national leader in the cause of academic freedom, publicly making the case that the ability of scholars to teach and pursue research free from political dictation is essential for a democracy.

|

|