loading

loading

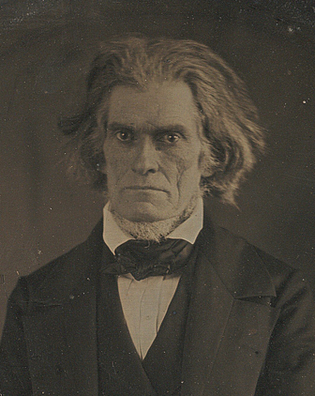

Old YaleYale, Calhoun, and the War of 1812Yale and a favorite son rarely saw eye to eye.  Beinecke LibraryJohn C. Calhoun, Class of 1804—shown here in a daguerreotype taken a year before his death in 1850—was and remains one of Yale's best-known but most controversial alumni. View full image

At Yale, the declaration of war 200 years ago that began the War of 1812 had a personal side. Yale, like most of New England, was firmly against war. But the leader of the pro-war faction in Congress was one of Yale’s favorite sons: John C. Calhoun, Class of 1804, who had made a name for himself on the campus as a future leader. Born in South Carolina in 1782, Calhoun worked on the family farm for several years. He was admitted to the junior class at Yale in 1802 and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. Although Yale president Timothy Dwight ’69 was a staunch Federalist, he encouraged Calhoun, a Jeffersonian, to express his political opinions. During a recitation on politics, he asked Calhoun to speak on the legitimate source of power—and was so impressed that he later predicted the young man would become president. Calhoun was selected to speak at commencement on “Qualifications Necessary to Form a Statesman.” After attending law school, Calhoun was elected to the South Carolina legislature. In 1811 he entered the US House of Representatives and quickly joined the “war hawks,” who urged retaliation against Britain for interference with US shipping and suspected support of Indian attacks. As chair of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Calhoun wrote its report condemning Britain. It was he who presented the war bill, which passed 79–49—with all the New England states voting in opposition. On June 18, 1812, President James Madison declared war. President Dwight criticized the war from his pulpit in the Yale Chapel a month later: “A great part of our countrymen believe the war in which we are engaged, to be unnecessary and unjust.” The sentiments of other Yale trustees and administrators are known today because they served as public officials. Roger Griswold ’80, a Yale trustee, was governor of Connecticut; on learning of the “offensive War,” he called a public fast. Other anti-war alumni included James Hillhouse ’73, Yale’s treasurer, a US senator until 1810; Chauncey Goodrich ’76, Yale trustee and US senator; and many others. At the war’s end, in 1815, Calhoun was a nationalist. But by 1828, he had become a champion of the view that “the Constitution of the United States is, in fact, a compact, to which each State is a party.” A few decades later, most Southern states invoked this argument when they seceded from the Union. But Calhoun is best known and most criticized today for his defense of slavery—as “a positive good.” Calhoun did not become president, but served through four decades as congressman, senator, secretary of war, vice president, and secretary of state. After his death in 1850, Yale president Theodore Dwight Woolsey ’20, ’23MA, remembered him as “that eminent Southern statesman, whose depth of thought and earnest purpose … gave him unlimited sway over the minds of such as embraced his views of the Constitution.” Fifty years after the Civil War, a Yale historian wrote: “Calhoun influenced the political history of the United States more deeply than any other graduate during the first two centuries of the college’s history.” In 1933, when Yale named the new residential colleges for prominent historical alumni, Calhoun was among them—a decision that still troubles many alumni. Calhoun College today is the only residential college with both an African American master (once Jonathan Holloway returns from sabbatical) and an African American dean, Leslie Woodard.

The comment period has expired.

|

|