loading

loading

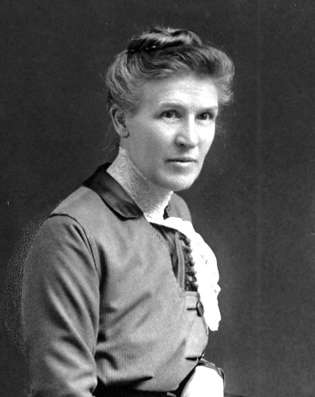

The pioneers Vassar College ArchivesLaura Johnson Wylie View full imageLaura Johnson Wylie Born in Milton, Pennsylvania, in 1855, Laura Wylie was valedictorian of her class at Vassar in 1875. She taught Latin and English at the Packer Institute in Brooklyn for 14 years; after graduating from Yale, Wylie was immediately hired by Vassar and became head of the English department within two years. (The poet Edna St. Vincent Millay likely studied with her there.) A Yale professor made her book Studies in the Evolution of English Criticism a regular part of his course on poetry, and she edited and published several other books. Wylie’s life partner was another Vassar English professor, Gertrude Buck; they were professional partners as well, and together they had a major role in shaping the development of writing programs in the United States. During her long academic and civic career, Wylie was a leader in the women’s suffrage movement, helping to establish and serving as president of the county suffrage organization. One of several women’s groups she helped organize during her life was the Nantucket Maria Mitchell Association, named for the eminent astronomer who had taught her Yale classmate Margaretta Palmer. The association’s obituary recalled, “One of her instructors said of her: ‘Don’t compare her to the rest of us—she is a genius, we are mere mortals.’” After Wylie’s death, her brother wrote Yale’s president to thank him for his expression of sympathy and added, “I have often heard her speak of her connection with the University and I know that she felt that it was among the happiest experiences in her well rounded life.”

Sara Bulkley Rogers We have little information, and have not yet found any photographic trace, of Sara Rogers, sister and Yale classmate of Cornelia. Sara received her BA from Columbia in 1889 (through the Collegiate Course for Women, the program that later became Barnard College) and her MA in history from Cornell. Her Yale dissertation was on civil government in early New England. After graduating she traveled to Oxford, where she attended lectures by a constitutional theorist, and then spent several years traveling in Germany, France, and Italy. Once back in the United States, she continued doing research on political history. She also wrote fiction. Publisher’s Weekly called her 1900 book, Ezra Hardman, M.A., of Wayback College: And Other Stories, “one of the best collections of college stories in recent years.” In Ezra Hardman, she created a hapless academic hero—a midwestern bumpkin unable to measure up or fit in at his snobbish eastern graduate school. “It had seemed to him,” Rogers wrote, “if only he might secure a doctorate from some eastern college there was nothing he might not become.”

Manuscripts & ArchivesElizabeth Deering Hanscom View full image

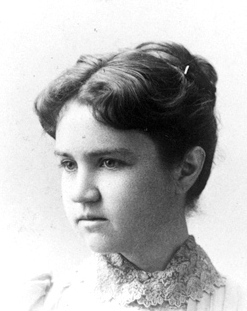

Elizabeth Deering Hanscom After Elizabeth Hanscom died, the archivist at Smith College, where Hanscom taught English, wrote, “Miss Hanscom delighted in telling us that she was actually the very first woman to receive the [Yale] diploma through the accidental arrangement by alphabet of the women candidates in that first year.” Hanscom, born in Maine in 1865, earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Boston University in 1887. She joined the English faculty at Smith after graduating from Yale and taught there for 38 years, becoming a professor in 1905. She was elected to the Council of the American Association of University Professors. According to the New York Times, she “introduced the study of American Literature” at Smith “at a time when the subject was not studied generally in American institutions of higher learning.” She published several books, including The Friendly Craft (1910), which collected her personal favorites from a vast number of letters she had read by eminent Americans—“the gleanings of several years in some of the pleasant by-paths of American literature”—including Benjamin Franklin, Helen Keller, Henry James, Robert E. Lee, Louisa May Alcott, and many others. Hanscom was active in the suffragist movement and championed the intellectual seriousness of women’s colleges; writing in the journal Education Review in 1901, she declared that women’s colleges should never be thought of as promoting “womanly virtues.” She lived to see World War II begin and end, and in 1937 she wrote passionately about it: “In this sad year of war and human wreckage, we need the young around us to give semblance of merriment. The Christmas evangel sounds strangely, almost on deaf ears, this year; but I am not discouraged, being sure that eventually peace will be established on earth.”

Wellesley College ArchivesCharlotte Fitch Roberts View full image

Charlotte Fitch Roberts Charlotte Roberts became an associate professor of chemistry at her college, Wellesley, even before she earned her doctorate. Roberts, who spent most of her childhood in Greenfield, Massachusetts, received her bachelor’s degree in 1880; Wellesley made her a graduate assistant in 1881, an instructor in 1882, and an associate professor in 1886. She spent the year of 1885–6 in Cambridge, England, working with Sir James Dewar, a well-known chemist and physicist. In 1896 she published The Development and Present Aspects of Stereochemistry; her Yale professor called it “the clearest exposition of which we have knowledge of the principles and conditions of stereochemistry,” adding, “there is nothing in English which covers similar ground so broadly and so lucidly.” Roberts became a full professor at Wellesley in 1896, chair of her department, and eventually, a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. She devoted much of her scholarship to studying the development of ideas in chemistry, traveling to Europe to learn from other scholars and formulating her own theories. A chemistry professorship at Wellesley bears her name.

The comment period has expired.

|

|