loading

loading

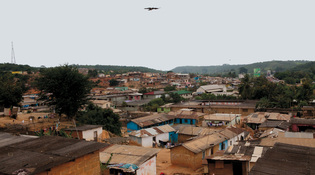

Far from home, briefly Jane HahnYamoransa, a town of some 4,700 near the Atlantic coast, was the site of a Yale Alumni Service Corps trip this past summer. View full imageEmmanuel Arthur raises his hand nearly every time David Schneider or Michael Morand ’87, ’93MDiv, asks students a question about “Praise Song for the Day,” written by Yale professor Elizabeth Alexander ’84 for Barack Obama’s inauguration. Morand moves through the poem, asking, “Are there any words you don’t know?” One hard word is “declaimed,” in stanza six: We encounter each other in words, words / spiny or smooth, whispered or declaimed, / words to consider, reconsider. “Whisper, whisper,” murmurs Morand, and then: “DECLAIM! A pastor, when he gives a sermon, declaims.” Two classrooms away, a teacher named Felix Koranchie watches students building four types of bridge trusses with craft sticks. Koranchie is on summer break from Yamoransa’s Mount Zion Methodist Junior High School, where he teaches religion and information technology, but stopped by “to learn something new from my brothers who have come here.” While the students work in teams, he and media arts specialist Anne Kornfeld ’86MFA have been discussing “student-centered” instruction. “The teacher should be a facilitator,” Koranchie says. “The old idea is just standing in front of the board talking to the students.” Meanwhile, Morand is wrapping up. They’ve completed a quiz on American culture. (It also asks what color Morand’s socks were yesterday. Today’s are purple.) “I will tell Professor Alexander how well you learned her poem,” he tells the students. After class, I ask Emmanuel what he thinks of Morand. “I like everything about him,” says Emmanuel. “I plan to become like him in the future.” Become like him? In what way? “The way he talks to people,” Emmanuel replies. “He’s very patient. He don’t rush. When he talks to you he wants you to understand what he’s saying. And I love him so much.” Emmanuel wants to be a doctor. “I want to save lives. I don’t want people to die every day.” Down the hill at the medical clinic, behind a curtain sewn from cotton flour sacks, physician Ricky Schneider ’73, ’77MD, is interviewing a 28-year-old man whose two-year-old son is lying motionless in his lap, eyes shut. Another volunteer has already examined the little boy and treated him for malaria, which kills 20,000 children in Ghana each year. The father tells Schneider he has malaria, too. He gets malaria three or four times a year, so he knows the symptoms: chills and no appetite. He’s been feverish for five days, but his long hours as a mason have left him no time to buy medicine. Here he can save $1 by getting the pills for free at the clinic pharmacy. Schneider writes the prescription. “On the first day, we looked under the microscope for malaria,” he says. “Now if they have a recent illness that they describe as malaria, we treat them.” The patients were always right. An hour later, I catch sight of the father again. Despite his illness, he has joined the volunteers and is shoveling gravel at the technology center. In the evenings, under the roofs of three surfside gazebos at the resort, the Yale volunteers talk, and they worry. Over meals of rice, fried fish, fried chicken, French fries, and fried plantains, they ask: where will Yamoransans get follow-up medical care when the temporary clinic closes? Will anyone finish building the center? Will Yale come back next year? Among those who worry is Evans Yeboah, a 28-year-old Ghanaian investment analyst who is using vacation time to lead the AFS volunteers. If Yale wants credibility, we must return, says Yeboah. “If you can’t sustain a community project, it becomes a tourist project,” he tells me. “Next year, if you don’t continue, then you are not sustaining.” Why did the AYA choose Ghana? The country has critical advantages: it’s a stable democracy; it has a growing economy (newly lubricated by oil); many Ghanaians speak English; and direct flights connect New York with Accra. And Yale already has connections here, with the University of Ghana and others. Ghanaian health officials—and Ghana’s new president, John Mahama—have spent time at Yale through its Global Health Leadership Institute. Several Yale professors have long-term research projects in Ghana. Emmanuel Asiedu, a Ghanaian investment banker, spent a semester at Yale as part of the university’s World Fellows program for “emerging leaders.” It was he who put the AYA in touch with the AFS in Ghana, and through AFS with a university near Yamoransa and with local tribal chiefs. If the service trips strengthen these ties or create new ones, they will strengthen Yale’s claim to being a global university. “There are only a few comprehensive global universities,” says Morand, who is a communications officer at Yale. “We are one of them. To remain one of them you have to develop even deeper partnerships around the world.” And despite their concerns, many alumni love the trips. Yamoransa is the second service trip for New York asset manager Puneet Batra ’02MS. Batra says he enjoys the type of alumni who join service trips; they’re not only smart, but also down to earth. California financial software saleswoman Lata Prabhakar ’97 is on her fifth trip. For her, the best part is the chance to make connections with local people: “What other opportunities do you have to develop a relationship in just a few days?” She still keeps in touch with a young woman she met in China.

|

|