loading

loading

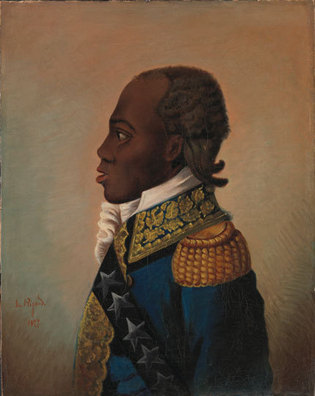

Arts & CulturePortrait of a revolutionaryObject lesson: The leader of history's most successful slave revolt, rethought. Erica Moiah James is an assistant professor in art history and African American studies.  Yale University Art GalleryIn 1877, long after Toussaint Louverture’s death, Haitian artist Louis Rigaud painted this oil portrait of a man who had always been depicted very differently. The portrait is now part of the collections of the Peabody Museum. View full imageIn 1791, an event was set in motion that would reshape the Atlantic world. At Bois Caiman in northern Haiti, a group of enslaved Africans gathered to fight for their freedom in what became known as the Haitian Revolution. A former slave, François Dominique Toussaint—who later took the surname “Louverture” (“the opening,” or “he who leads the way”)—soon emerged as its leader. A self-taught expert in guerrilla-style warfare and a masterful battlefield tactician, as well as a shrewd diplomat and prudent economic manager, he would lead his followers in unifying the entire island of Hispaniola by 1801 as a self-governing protectorate under the French flag. In the process, they emancipated themselves from slavery. Although Louverture died in 1803, imprisoned by Napoleon, within the year Haiti became the first free black republic in the world. Many images of Toussaint Louverture exist, but none were produced during his lifetime. The artist Louis Rigaud completed the painting shown here, the earliest known portrait of Louverture by a Haitian artist, in 1877. It was the first in a suite of portraits he produced of every Haitian leader from Louverture to the sitting president at the time; they are now part of the Yale Peabody Museum collections. Aesthetically, it is in direct conversation with a number of verbal and visual representations of Louverture produced during the nineteenth century. In 1802 Marie-François Auguste de Caffarelli du Falga had interviewed Louverture while he was imprisoned at the Fort de Joux in the Jura Mountains of France. Du Falga described him as having “big eyes, prominent cheekbones, a flat but rather long nose, a large mouth, no upper teeth, a prominent lower jaw with long and salient teeth, sunken cheeks, an elongated face.” This description, among others, influenced many artistic renderings of the Haitian leader over the years, often with troubling results. It is useful to consider that French observers saw a man changed by his harrowing journey to France and by the inhumane treatment that would kill him in prison, and that their own perceptions were affected by his physical difference from French ideals of beauty. Yet it is Nicolas Maurin’s simian portrait of Louverture, painted in 1832 and no doubt based on du Falga’s description, that is historically regarded as his “true” image. Rigaud, who was surely aware of the history of representing Louverture, made a conscious decision to craft an alternative vision of the man. Infrared views of the painting reveal, beneath the upper paint layer, a brown oil sketch defining the features, indicating a level of intention for the final image. The painting presents Louverture, in uniform except for his bicorne hat, as the slight, middle-aged, graying man described by contemporaries in Haiti—nattily dressed, straight-backed, and determined. He is exceptional in that, unlike in the Maurin image and others, there is no suggestion of caricature. The portrait came to Yale in the ’60s, after a journey that took almost 100 years. It was first shown in 1882 in Port-au-Prince. Then the suite of portraits traveled to the 1884 World’s Fair in New Orleans, to be exhibited at the Colored People’s Exposition, a segregated display whose theme was Haiti. In 1885 they were sent to the Smithsonian. There they remained until 1963, when Yale anthropology professor Sidney Mintz, a Caribbean specialist, had the entire suite transferred to Yale. Recently restored, the portrait is now on display at the Yale University Art Gallery.

The comment period has expired.

|

|