loading

loading

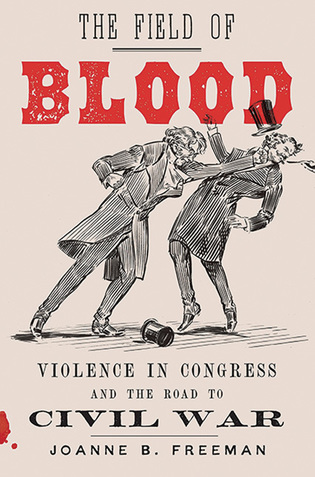

Reviews: January/February 2019 View full imageThe Field of Blood David Greenberg ’90 is a historian at Rutgers University. Joanne Freeman is perhaps our foremost scholar of American political violence—not in the modern variety of assassinations and terrorism, but in its nineteenth-century forms of feuds, dueling, and canings. Her first book, Affairs of Honor, showed a seamy underside to the often-idealized world of America’s founders, revealing how concerns about reputational virtue led to ritualized violence and gutter politics. As an editor of Alexander Hamilton’s papers, Freeman shed light on his famous duel with Aaron Burr well before Lin-Manuel Miranda spun it into Broadway lyrics. This expertise has prepared Freeman well to write her timely new book, The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War, a kind of sequel to Affairs of Honor. Readers who imagine that today’s vicious partisanship knows no precedent will be surprised to read Freeman’s vivid account of an antebellum political culture in which the halls and floors of Congress themselves were rife with physical intimidation, brandished weapons, and drunken brawling. Many people know about the famous 1856 altercation in which Preston Brooks of South Carolina beat the Massachusetts abolitionist Charles Sumner to a bloody pulp with his gold-tipped cane. But most of us, historians included, will be amazed to learn that between 1830 and 1860, congressmen fought one another, often with weapons, on more than 70 occasions. Drawing on a vast trove of research, Freeman skillfully brings to life a forgotten world in which drunken congressmen slept on couches, tobacco spit covered the House floor, and proud representatives pulled bowie knives on one another. Entertaining as Freeman’s stories can be, they also serve a larger argument. Many fights were rooted in partisan and sectional differences, centering on slavery. Legislative politics proved unable to bridge fundamentally different attitudes about slavery. One challenge of a book like this is how to give a sprawling account narrative coherence. Among other devices, Freeman uses Benjamin Brown French—a House clerk and diligent diarist—as a kind of Greek chorus figure. And the forward march to disunion imposes needed structure. Knowing how prone to violence Americans’ elected representatives were helps explain how citizens themselves could take up arms against each other.

|

|