loading

loading

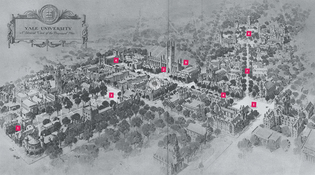

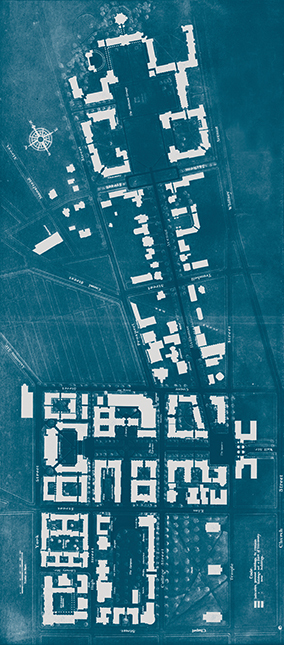

Left on the drawing board View full image View full imageGrand plansThe most ambitious campus plan ever proposed for Yale was drafted in 1919 by the noted architect John Russell Pope. It would have reorganized the entire campus. An alumnus, Francis Garvan ’97, commissioned the plan; the university gave the effort its blessing, but did not participate in the funding or the process. The new plan came as Yale was reorganizing itself in the aftermath of World War I, with an eye toward its image as a modern university—not just an undergraduate college. For that to happen, writes Patrick Pinnell ’71, ’74MArch, in his guide to Yale architecture, “the center of the institution had to be moved off the Old Campus.” And as it happened, the university had recently received an enormous bequest from John W. Sterling ’64 that would fuel a major building boom. Pope’s plan was part of the “City Beautiful” movement, a planning approach of the day that emphasized grand processional streets or walkways, along which buildings were organized to produce long sightlines, with monumental buildings or towers at the ends as focal points. (Think of the boulevards of Paris or Washington, DC.) Such a street or path is called an “axis” in city-planning jargon. As Erik Vogt ’99MEnvD describes in an essay in the book Yale in New Haven, Pope proposed three such axes. One established a clear sightline from Vanderbilt Hall (1 in the drawing above), across the Old Campus and beyond to where the Beinecke now stands (2); Durfee Hall (shown removed in the location marked 3) would have been sacrificed in order to open up the view. A second axis, running along Wall Street (4) and crossing the first, would be part of a new campus quad for the university as a whole. (The intersection of these two axes was apparently the origin of the name Cross Campus.) There would be a grand public square and campus entrance (5) at the eastern end, on Temple Street, and a massive gymnasium (6) at the western end, where Sterling Library now stands. The third axis would be along Hillhouse Avenue (7). Pope’s plan was to extend Hillhouse one block south, so it would stretch all the way from Science Hill (8) to the new campus entrance. As for architectural style, Pope proposed neo-Gothic. Saybrook and Branford Colleges (then known as Memorial Quadrangle) had just been completed in that style, and they were widely admired. Pope wanted consistency: neo-Gothic for all the university’s new buildings. He even wanted to hide Commons (9) and Woolsey Hall, which were in the classical style, by blocking them from view with a huge, cathedral-like neo-Gothic library (2). Yale balked at that idea. It also balked at Pope’s concept for a vast gymnasium at the western end, which would serve as the focal point of the new central campus. Pope saw the raised court in front of the gym as Yale’s major ceremonial space—and the university wasn’t sure that Yale graduates should receive their diplomas with a gym as backdrop. (Pope may have been humoring his patron. Garvan was a big believer in college sports.) The university was also uncomfortable with the way Pope’s grand design opened Yale up to New Haven. For the past 50 years, Yale had been walling itself off from the city and creating courtyards, and it was not ready for a change. In 1924, when architect James Gamble Rogers produced a less ambitious, more inward-looking plan, the university accepted it. But Pope’s plan had an influence. Thanks to Pope, most of the buildings Yale constructed in the 1930s were neo-Gothic. And today’s Cross Campus is modeled after his idea for a new campus quad. Fortunately, it’s dominated by a library, not a gymnasium.

The comment period has expired.

|

|