loading

loading

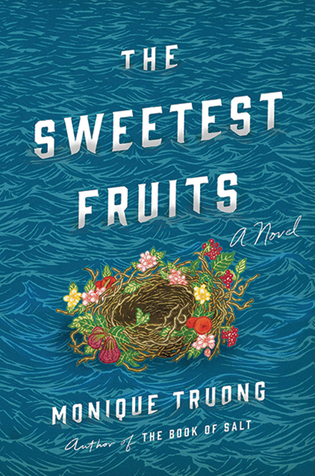

Reviews: November/December 2019 View full imageThe Sweetest Fruits Sylvia Brownrigg’s most recent novel, Pages for Her, was published in paperback in 2018. Born on one of the Ionian islands, child of a Greek mother and Irish father; educated in Ireland, France, and England; breaking first into journalism in Cincinnati, then moving to New Orleans, the West Indies, and finally Japan, where he married a samurai’s daughter and had four children—the restless, stateless Patricio Lafcadio Hearn seems a thoroughly modern character. Yet Hearn was born in 1850, and his most famous books, about Japanese legends and ghost stories, were published at the turn of the last century and helped to introduce Western readers to a culture that had previously been closed to them. At the time of his death in 1904, Hearn was also known by his Japanese name, Koizumi Yakumo. The appeal of this anomalous historical figure is obvious, and in her novel The Sweetest Fruits Monique Truong ’90 (author of The Book of Salt) imagines the colorful, contradictory Hearn back to life through the stories of three women who loved and lost him. Interstitial passages written by his contemporaneous biographer, Elizabeth Bisland, move his saga forward. In the book’s three sections, Hearn’s name and geographies shift and change. As baby Patricio, he is a narrative spur for the passionate Rosa, lyrically describing a sheltered island upbringing and her brothers’ fierce resistance to her union with a surgeon from the British army. Framed as a tale Rosa unspools while crossing back from Ireland to Greece—having left beloved Patricio behind to be raised by a grim relative—these chapters establish the foundation story of a boy cut off young from his mother and his origins. Next is the Cincinnati story of Alethea Foley, the African American cook in the boarding house where Hearn lived when he got a job as a newspaper journalist. Fragrant with descriptions of her stack cakes and oyster stews, Alethea’s pages give us a “Pat” who is naïve about the dangers of their interracial marriage. The last, richest story is told by Koizumi Setsu, Hearn’s Japanese wife, who adored him, while acknowledging that his secrets eluded her, too. “I remind myself that we are all capable of having two hearts. . . . Perhaps you had even more.” After reading Truong’s dreamy, evocative novel, a reader may do well to turn to Hearn’s collected works—to encounter the words of the man who inspired these women’s serial devotions.

|

|