Daniel Baxter

Yan Phou Lee, from an 1887 photograph.

View full image

Daniel Baxter

Yan Phou Lee, from an 1887 photograph.

View full image

Illustrations: Daniel Baxter.

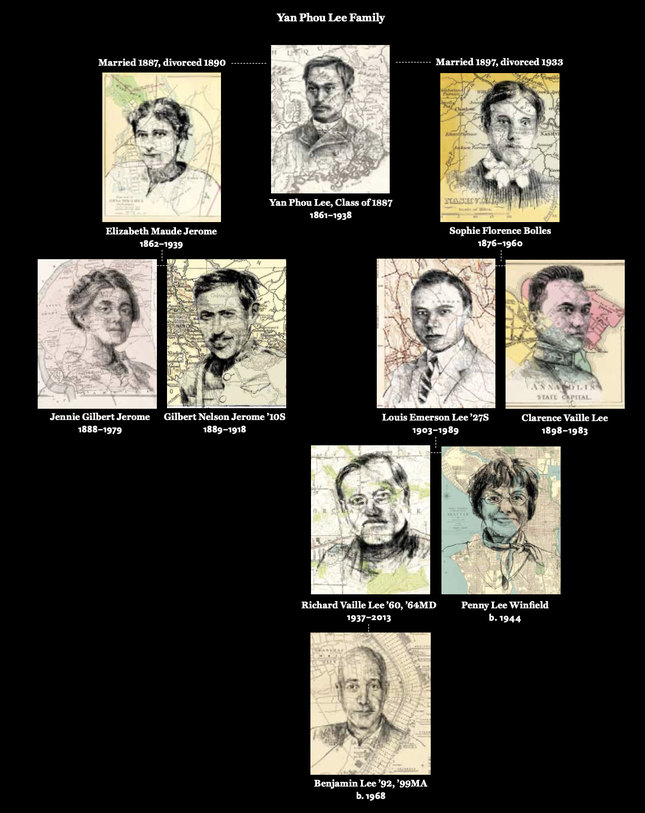

Yan Phou Lee married twice and had four children during his half century in the United States. The maps behind the faces in this family tree represent some of the places they lived. Lee’s first wife, Elizabeth Jerome, was born and lived most of her life in New Haven. Their daughter, Jennie Jerome, spent four important years at Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts. And their son, Gilbert Jerome ’10S, died in World War I when his plane was shot down in France.

Lee met his second wife, Sophie Bolles, when he was working in her hometown of Nashville, Tennessee. Their older son, Clarence Lee, studied and later taught at the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. Their younger son, Louis Lee ’27S, raised his family in New Canaan, Connecticut. Louis’s daughter, Penny Winfield, now lives in Seattle, Washington. Her brother, Richard Lee ’60, ’64MD, raised his family in Orchard Park, New York. And Richard’s son, Ben Lee ’92, ’99MA, now lives in Shanghai, where he is a high school principal.

View full image

Illustrations: Daniel Baxter.

Yan Phou Lee married twice and had four children during his half century in the United States. The maps behind the faces in this family tree represent some of the places they lived. Lee’s first wife, Elizabeth Jerome, was born and lived most of her life in New Haven. Their daughter, Jennie Jerome, spent four important years at Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts. And their son, Gilbert Jerome ’10S, died in World War I when his plane was shot down in France.

Lee met his second wife, Sophie Bolles, when he was working in her hometown of Nashville, Tennessee. Their older son, Clarence Lee, studied and later taught at the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. Their younger son, Louis Lee ’27S, raised his family in New Canaan, Connecticut. Louis’s daughter, Penny Winfield, now lives in Seattle, Washington. Her brother, Richard Lee ’60, ’64MD, raised his family in Orchard Park, New York. And Richard’s son, Ben Lee ’92, ’99MA, now lives in Shanghai, where he is a high school principal.

View full image

Richard Lee ’60, ’64MD, had big news: he had decided he wanted to marry his girlfriend Susan. He was just out of Yale College and about to start med school. When he went home to New Canaan, Connecticut, to tell his parents, his father took him into the library—and closed the door.

His father, Louis Lee ’27, had a secret. As far as Richard and his sister Penny knew, the Lees were white people. (Their mother was “as Irish as Paddy’s pig,” Penny says.) But now, Louis told Richard that his grandfather, who had left the family more than 30 years earlier and was presumed dead, was a man from China named Yan Phou Lee. “My father and his older brother never spoke of him, except between themselves,” Richard Lee wrote decades later. “The reason I was being told was because my father was concerned that should the fact of my Chinese heritage become known, Susan and her family might reject my proposal and refuse to let us marry.”

In the end, it was not a deal breaker. And over time, after a distinguished career in medicine, Richard Lee began to learn more about the man whose remarkable life story had been kept from him. His grandfather Yan Phou Lee, who had himself graduated from Yale College in 1887, was an author, lecturer, and editor whose book When I Was a Boy in China was the first book published in English by an Asian American author. (His name is romanized as Li Enfu in the modern Pinyin system; we are using the version of his name he used personally and professionally throughout his life in America—with surname last.)

Over more than 50 years in the United States, Lee participated in a groundbreaking program that educated Chinese boys in American schools, lectured widely about Chinese culture, wrote and edited for newspapers and magazines, and fathered four children with impressive life stories of their own. His story—and his family’s—is a tale of western idealism, virulent racism, bravery, heartbreak, and tragedy in four generations of Yale alumni.

That story begins with another Chinese Yale graduate. Yung Wing, Class of 1854, was taught by Yale-trained missionaries in Macau and Hong Kong before traveling to Massachusetts at age 18 to study at a prep school called Monson Academy. He went on to Yale and became the first Chinese student to graduate from any North American university. Yung (Róng Hóng in Pinyin) would also be the only Chinese Yale graduate for more than two decades after that. But even before he left Yale, Yung later wrote, he was “determined that the rising generation of China should enjoy the same educational advantages that I had enjoyed; that through western education China might be regenerated, become enlightened and powerful.”

In 1871, while working in China as a government official, Yung was able to put this idea into practice. He convinced Beijing to fund a program called the Chinese Educational Mission, which would bring 30 Chinese boys ages 12 to 16 to New England every year to begin an American educational journey from grammar school through college. Yung sold the idea as a way of bringing technical and engineering expertise to China so that they could manufacture their own industrial and military products.

Yung was chosen as one of two commissioners in charge of the program. They recruited boys mostly from the Shanghai and Guangdong (Canton) areas. Finding boys who already had sufficient education to begin the program wasn’t easy; study abroad was a big step off the path of Confucian education that led to elite civil-service careers. Many of the boys who signed up were the children of merchants. One of the few who came from a family background of scholar-officials was 12-year-old Yan Phou Lee. Born in Xiangshan (Fragrant Hills) in Guangdong Province, Lee was the grandson of a “literary subchancellor”—an education official. Lee’s father, who had a business renting sedan chairs for weddings, had died by the time he was 12. When a cousin in Shanghai told the family about the Chinese Educational Mission, Lee “said yes without hesitation.” His mother agreed to the plan. “A chance to see the world was just what I wanted,” he later wrote in his memoir.

The boys would be brought first to Shanghai for preparatory work and English language study; 30 per year would be chosen to go abroad. Lee was sent abroad in the second year’s cohort of 30.

In 1873, Lee and his fellow students boarded a ship in Shanghai and sailed to San Francisco via Yokohama, then traveled to Springfield, Massachusetts, by train. Lee would later write wryly in his memoir that “nothing occurred on our Eastward journey to mar the enjoyment of our first ride on the steamcars—excepting a train robbery, a consequent smashup of the engine, and the murder of the engineer.” He goes on to describe a harrowing experience complete with gunfire, stolen gold bricks, and robbers dressed as Indians. Given that Lee’s book was written for children, it’s tempting to wonder if this story was made up or embellished. But contemporary accounts back him up: a train was robbed in July of that year—by Jesse James, no less—near Adair, Iowa, and a newspaper reported that “among the passengers were thirty Chinese students en route to Springfield, Massachusetts.”

During the previous two years, Yung Wing had moved to Hartford and organized the mission’s headquarters. Through his connections at Yale and in the Congregational church, he established a network of host families in Connecticut and western Massachusetts with whom the students would live while attending local schools. They would assemble periodically in Hartford, where the CEM built an elaborate Victorian headquarters building, for Chinese lessons to ensure they did not lose their first language.

Lee was placed in Springfield with Henry Vaille, a physician, and his wife Sarah. Lee recounted that upon his first arrival at the station in Springfield, Sarah “put her arms around me and kissed me . . . that was the first kiss I ever had had since my infancy.” (Lee remained close to his host family later in life; he gave his son Clarence the middle name “Vaille.”)

The Chinese students soon proved successful and popular in their local schools and a cause célèbre in progressive circles in Hartford. Near the CEM’s headquarters were the homes of authors Mark Twain and Harriet Beecher Stowe and the Asylum Hill Congregational Church, led by the influential Reverend Joseph Twichell ’59, a Yale trustee. Twichell would become an important friend and ally to the program and many of the students, including Lee. By 1877, the CEM had seen its first student finish college: Zeng Pu, who was older and better educated in English than his peers, got his degree from Yale’s Sheffield Scientific School, making him the first Chinese Yale graduate since Yung Wing.

Lee went to public schools in Springfield before moving on in 1878 to Hopkins School in New Haven, where he boarded with another family. He graduated in 1880 at the top of his class, also winning top honors in English composition. That fall, he was one of six CEM students to enter Yale. (Yale was by far the most popular college among the CEM students: of 43 who entered college, 20 enrolled at Yale. MIT was second with 8.)

But while Lee and his fellow students had been making great academic strides, the Chinese government was hearing reports that made them anxious about the CEM. Embedded in Christian homes and steeped in American culture, the students were absorbing more than the scientific and engineering expertise Yung Wing had promised. Many of them adopted American-style clothes, and a few cut their queues—the braids that were required of all adult males.

More troubling, many became curious about Christianity and in some cases seem to have surreptitiously converted. Lee later wrote that he was swayed by an 1876 revival in Springfield by the famed evangelical minister D. L. Moody. “I had a personal interview with Mr. Moody, and was strengthened in my resolution to be a Christian.” He kept this quiet, though, for fear of being sent home.

In the summer of 1881, word reached Hartford that the Chinese government was ordering the students home; the CEM was unceremoniously and immediately terminated. Lee was forced to leave Yale after just one year. After a tearful sendoff from a crowd of friends and host families at the Hartford train station, the students retraced their journey across America in reverse and sailed back to China.

Their reception in China was far less warm, though. Although the students were essentially pledged to the government, the authorities thought their western education, rusty Chinese language skills, and Americanized attitudes made them unsuitable for the kinds of civil service jobs for which they might have been qualified. They were instead assigned mostly to technical jobs in the navy; Lee was sent to the Tianjin Naval Academy, much to his displeasure. In a newspaper interview some years later, he said that “we were treated on our return more like criminals than innocent sufferers. We were confined and watched lest we should run away.” After six months, Lee did just that, going AWOL while on furlough and making his way to Hong Kong.

He spent the next year or so working to raise money for passage back to America, and during this time he formally became a Christian through a Presbyterian church in Canton. On Christmas Day 1883, he boarded a steamer for New York—after first cutting his queue.

Without support from his family or the Chinese government, Lee had to be resourceful to find a way back to Yale. Relying on his writing and oratorical skills, he began a long career of lecturing to American audiences about China and its customs, and he got a job with a magazine for children called Wide Awake, which published 12 articles of his about childhood in China. Those articles would be adapted into the 1887 book When I Was a Boy in China, the volume that allows Lee to claim the mantle of first Asian American author to publish a book in English.

In the fall of 1884, with the help of the income from his lectures, he returned to Yale as a sophomore in the Class of 1887. He won prizes in oratory and English composition and was elected to the Pundits and Phi Beta Kappa. And when his commencement came, he was chosen to be one of the student speakers.

In 1887, five years after the Chinese Exclusion Act prohibited immigration from China, the “Chinese question” was still being broadly debated in American politics. To the extent that Lee had established himself as a writer and speaker up to his graduation, his persona was that of a genial guide to foreign customs, working to make Chinese culture seem friendly and benign to an American audience. But his commencement speech was something else: a full-throated defense of Chinese immigrants and an excoriation of American prejudice. It was a smash hit with the elite Yale audience. The Hartford Courant reported: “The oration of Yan Phou Lee of Fragrant Hills, the Chinaman, one of the set pieces of the Center church commencement exercises, was a phenomenal affair. It was frequently interrupted by loud and long applause, which seldom happens at that formal season. He gave his mind a very free delivery, and his was the Chinese side of the story. The way in which he ‘let into’ the government policy made the representatives of the government, to say the least, very attentive listeners.”

In fact, one of those listeners, New York politician and future senator Chauncey Depew ’56, joked later in the day that “This morning I heard a dozen—including Yan Phou Lee—speak at Center Church, and I have come to the conclusion the Chinese must go. We can’t stand this kind of competition, and Senator [William ’37] Evarts and I don’t propose to.”

At 26, Lee seemed to be on top of the world: newly graduated from Yale, with plans for grad school in the fall; a book just published; a well-connected set of friends. And just a week after commencement, he was to be married to a wealthy young New Haven woman from a family that dated back to the city’s founding.

There is not much in the record of how Lee met 24-year-old Elizabeth Maude Jerome, but they had been in the same town for some years and probably crossed paths in church and social circles. Jerome was the granddaughter of Hezekiah Gilbert, who owned land in what is now the West River neighborhood. (The family lived on Gilbert Avenue.) Elizabeth was her parents’ only surviving child. Gossipy newspapers estimated her expected inheritance to be between $65,000 and $100,000—between 2 and 3 million dollars today.

The wedding was held at the bride’s house. Reverend Joseph Twichell performed the ceremony, and the guests included a host of Yale professors and Yung Wing. Newspapers across the country reported on the marriage, with varying degrees of approval, curiosity, and titillation. (Searching for Yan Phou Lee’s name in newspaper archives is an education in the casual, smirking racism aimed at Chinese people in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.) The couple went to Watch Hill, Rhode Island, for their honeymoon, but the papers reported that they cut the trip short because “whenever they take their daily walks abroad they are gazed at by hundreds of curious eyes.”

By the end of 1889, the Lees had two children, Jennie and Gilbert. Lee did not stay in graduate school long, and in 1888, he had accepted a job offer from a Yale classmate in his family’s bank in San Francisco. Elizabeth had joined him there briefly but had soon returned to New Haven. When Lee came back to New Haven in 1890, the marriage ended in a scandal that resulted in more—and more lurid—media attention.

In May, newspapers reported that Elizabeth Lee had filed for divorce, accusing Yan Phou Lee of adultery. The Boston Globe reported that he had returned home ill from California and that a doctor had diagnosed him with “a constitutional disease which in his opinion could never be cured”—apparently a euphemism for a venereal disease. More than 50 years later, in a 1944 private letter to her family lawyer, Jennie Jerome would delicately suggest the same: “My mother divorced my father because Dr. Leonard Sanford [’90, ’93MD] said it was no longer safe for her to live with him, his private life being such that he had sunk very low indeed.” Jennie also claimed that her father had stolen money from his mother-in-law and that he “tried to introduce into her home a young Chinese girl, ostensibly as my nurse, really for purposes of his own.”

Lee declined to contest the suit, writing to Twichell that he didn’t want to “have my dirty family linen washed in court.” He told the New York Evening World that his mother-in-law had been the source of much of the trouble, that she hated him “like poison.”

After this sensational parting, Lee and his New Haven family seem to have severed ties almost completely. Elizabeth eventually returned to using her maiden name, Jerome, and Gilbert and Jennie adopted it as well. In her 1944 letter, Jennie writes that “Mother grew to detest him and grieved all her life long that she had taken such a drastic step in marrying him and placing upon her own mother so great a sorrow, and upon her children such a disgrace which brought us so much suffering.”

The divorce and the public scandal must have cost Yan Phou Lee some of the friendships and social capital he had built in New Haven and New England over the previous 17 years. After he left New Haven, he spent nearly a decade wandering from place to place and job to job, trying on different ways to use his unusual combination of elite western education and Chinese background—and no doubt encountering distrust and discrimination along the way.

The list of things he did between 1890 and 1900 is almost comically varied: he published a Sunday School journal in New York; worked as an assistant at a school for Chinese students in Wilmington, North Carolina; lectured in the South, sometimes billed erroneously as “Rev. Yan Phou Lee”; briefly attended medical school at Vanderbilt; worked at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair (as a fortune teller, if one newspaper account is to be believed); kept a country store; wrote an exposé for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch about gangsters running fan-tan games; worked as an interpreter in the courts in New York; ran the Chinese exhibits at the Tennessee Centennial Exposition in 1897 and the National Export Exposition in Philadelphia in 1899; and operated a truck farm in Delaware.

It was in Tennessee that Lee met his second wife, Sophie Florence Bolles, whom he married in 1897. In 1904, they settled in northern New Jersey with their sons, Clarence Vaille Lee and Louis Emerson Lee. The second marriage lasted 30 years, but it was not necessarily a happy one.

“It was not a very successful marriage,” says Penny Winfield, their granddaughter. “Sophie Florence was most likely not the nicest woman in the world, and Yan Phou Lee came here so young. He was close to his American [host] family, but I don’t think he ever developed the interpersonal skills to form close relationships.”

While the family stayed more or less in one place, Lee continued to have several irons in the fire professionally. He had stints as editor at two small-town New Jersey newspapers, and he had a poultry business in Chinatown for several years. In the 1920s, he was managing editor of American Banker magazine. Of this job, Lee wrote in his 50th Yale reunion book that he “did my best to make it a good financial journal” and that when he resigned in 1927, “the publisher was so glad to dispense with my services that he gave me a good watch. Very nice of him.”

His sardonic description suggests the discontent that led to his leaving his family that same year and returning to China at age 65. He at first taught English in Guangdong, then edited the English-language Canton Gazette from 1931 to 1937. But if Lee imagined he would find peace in a return home to China, he was sadly mistaken. In 1938, the Japanese began bombing Guangdong. In his last communication with his Yale class on March 29, 1938, Lee wrote that “we are having war here, inhuman, brutal, savage war. Japanese bombing planes raid the city every day—sometimes three or four times. One has to think of saving his life. Little time can he give to such a thing as Class histories.” Lee wrote both to his daughter Jennie and his son Clarence asking for money in 1938, but after that he was never heard from again. His family presumed he died in the bombings, but if his body was recovered, they were never made aware.

In an 1894 interview, Lee was already expressing a cynical attitude about his checkered career. “As for my future plans, I have learned not to make any,” he is quoted as saying. “My motto is ‘Expect nothing, and you won’t be disappointed.’”

Lee was neither the first Yale graduate nor the last to live a life of frustration after a promising start. It’s hard to know how much his difficulties were related to his sometimes acerbic personality, to his unusual adolescence, or to the prejudice he faced. “I think he was someone who didn’t feel at home anywhere,” says Ben Lee ’92, ’99MA, his great-grandson.

A development that might please Lee is his belated recognition as a pioneering Asian American author. Early scholars of Asian American literature dismissed Lee’s When I Was a Boy in China as “exotically quaint at best and damagingly stereotypical at worst,” says Floyd Cheung, a professor of English language and literature and American studies at Smith College. “More recent critics, including myself, have made the case that he used the genre to which he had access in order to reach a broad audience and do positive cultural work.”

In an interview with US immigration officials on his departure from America, Lee was asked “of what country are you now a citizen or subject?”

“It is hard to say,” he replied. “I took out my first papers to become a citizen of this country but I never got my last papers on account of the amendment to the Exclusionary law preventing me.”

“Then you must be a citizen of China, is that right?”

“I presume so, or a citizen of no country at all.”

The late Amy Ling, another scholar of Asian American literature, noted this ambiguity in an essay about Lee, framing it in a more positive way. Perhaps Ling’s words offer a way to consider Lee’s story that allows him to rest in peace: “Traditional Chinese believe that after death their bones must rest in Chinese soil and that they must have sons to carry on the family name and care for their spirit by placing ‘spirit’ money and food on their graves. Otherwise, they will be doomed to wander homeless and uncared for in the spirit world and cannot intercede on behalf of their living descendants. With no known resting place, Yan Phou Lee, in death as in life, remains literally between worlds, neither here nor there. No one can tend his grave, as he did not tend his adoptive father’s. However, as one of the first to occupy the difficult space of the frontier where two cultures meet, it is perhaps fitting that Yan Phou Lee has no known resting place, for he seems thereby to be asserting his independence from confining traditional Chinese customs, as well as his distance from US racism. He rests, therefore, in his own space, an Asian American place of distinction.”

loading

loading

14 comments

-

Mark Branch, 2:46pm April 28 2021 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

laura manuelidis, 10:46am May 04 2021 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Hoi Sang U, 1:55pm May 05 2021 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

jerome a. cohen, 6:58am May 07 2021 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Kristin Stapleton, 4:19pm May 07 2021 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Larry Li, 5:23pm May 07 2021 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Chris Wood, 12:51pm May 08 2021 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Yan-Yan Wang, 2:59pm May 08 2021 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

John Mark Ockerbloom, 9:53am May 10 2021 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Wei-Tai Kwok, 1:16am May 13 2021 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Hongyu Huang, 8:44am June 16 2021 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

tech village, 3:55am June 21 2021 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Cal C, 1:15pm July 19 2021 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Haynie Wheeler, 2:59pm July 22 2021 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.Writing about Yan Phou Lee's descendants in this article, we focused on those with Yale ties. But the Lee family wanted us to mention that there are other Lees out there. Clarence Lee and his wife Virginia had a son, Russell Vaille Lee, who died in 2020. Richard and Susan Lee had another son, Matthew Vaille Lee, who, like his great-grandfather, is a journalist; he has worked both in the US and abroad since 1991, and currently writes about diplomacy for the Associated Press. And Penny Winfield has three children--Richard Allen Winfield, Carolyn Vaille Winfield and Peter Li Winfield--and two grandsons, Quincy Scott Winfield and Louis Lee Winfield.

A great and good surprise about a Yale medical school student colleague and his courageous and talented grandfather. Dick Lee always an independent thinker and contributor to medicine in the same tradition as his ancestors and other graduates of Yale medical school.

Lee's experience was perhaps a little different from those in the Educational Mission who had returned to serve China. For more information about this Educational Mission, one might like to read "China's First One Hundred" by Thomas La Fargue.

This is a great story that will provide some novelists with marvelous material for a worthy successor to Orville Schell's recent My Old Home, a wonderful insight into both contemporary China and its implications for Sino-American human relations. Congratulations to Mr. Branch and the YAM for the story and its stunning display. Jerry Cohen, College '51 and Law '55.

Richard Lee was an esteemed colleague here at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. Another Yalie of my acquaintance, Edward Rhoads (Yale BA 1960, Harvard PhD 1970), is also a descendant of one of the participants in the CEM and has published a monograph on it: _Stepping Forth into the World: The Chinese Educational Mission to the United States, 1872-81_ (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2011).

What a history! The fact many of us could read this incredible story for the first time in our lives shows we as humans have progressed so much yet are still struggling on perhaps a higher ground! Truly inspiring and worth a blockbuster movie in the making!

I attended UB Medical School in the early 1990s and was a beneficiary of Dick Lee's great teaching and worldview. I was able to do a one month rotation in Beijing that he had started at my medical school. It was a wonderful experience and certainly broadened my view of medicine and humanity. I can not appreciate how he became interested in this part of the world and what motivated him to connect.

This is a well-written historical story with a great title!

For those interested, Yan Phou Lee's book is readable online, as is the book about his educational cohort mentioned in Hoi Sang U's comment:

_When I was a Boy in China_ (1887): https://archive.org/details/wheniwasboyinchi00leey_0/

_China's First Hundred_ (1942): https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001257999

This is an amazingly well-researched and thoroughly enjoyable story. Thank you for delving into and sharing this interesting slice of history of Chinese in America, and Chinese at Yale.

Wei-Tai Kwok '85

An amazing story about a pioneer culture bridging writer. I saw some of Lee's descendants in CCTV's 2005 five-episode documentary "Boy Students," which introduces the Chinese Education Mission to the broad audience in China.

good information it's very useful , thanks

tech village

What a fantastic story to learn about. What an amazing journey for this family. One of millions of such stories for the Chinese American community. Though, for many Asians who have been in America for over a century, there are probably many similar echos.

Bravo, Mark! As someone who knew Richard, Susan and Ben from my years at the Yale China Association, I had heard pieces of this story, but never the whole fascinating tale. Thank you for this. What an amazing chapter in Yale's and New Haven's history. And all through the lens of a remarkable family.