New Haven Museum

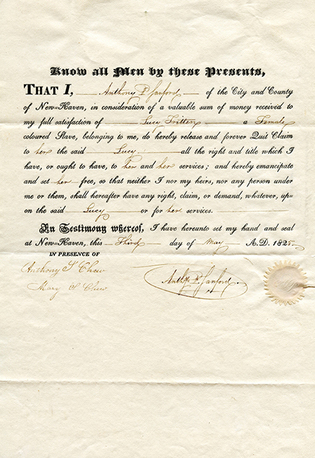

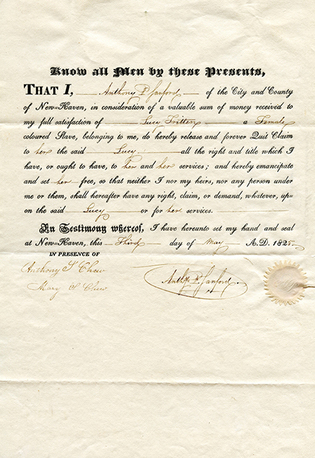

Emancipation papers for Lucy Tritton, one of the last two people sold in New Haven, in 1825.

View full image

The last sale in New Haven

My great-great-grandmother was born in South Carolina and was an enslaved person. When I did research about her, in Charleston, South Carolina, I was able to go and see a slave market—unlike in New Haven, where you cannot see the place where Lois and Lucy Tritton were sold as enslaved people in 1825.

That was when the last sale of an enslaved person occurred in New Haven. It was on the New Haven Green. Many of us have stood at a certain bus stop at Temple and Chapel, and very close to that bus stop is the place where Lois Tritton and her daughter, Lucy, were sold and then immediately manumitted. Lucy’s emancipation paperwork reads as follows:

Know all men by these presents that I, Anthony P. Sanford, of the City and County of New-Haven, in consideration of a valuable sum of money, received to my full satisfaction of Lucy Tritton, a Female colored Slave, belonging to me, do hereby release and forever Quit Claim to her the said Lucy all the rights and title which I have, or ought to have, to her and her services; and hereby emancipate and set her free.

What would it be like in the city, and on the Yale campus, if all of the history that we discussed in this conference on Yale and Slavery was set free? What would that history be like if it was visible and honest? If we were able to educate, engage, atone, and gather together—as members of the city, as members of the staff of the university, and as students—to talk about this history and bring it into the visible space?

When you walk around New Haven, you don’t see a colonial city. You don’t see a place that Indigenous people lived in. And you certainly don’t see the presence of, or the creation by, all of those African Americans who contributed so much to the making of Yale University and to New Haven.

There’s also the recent present. There’s Corey Menafee in 2016, taking that broom to destroy the window in Calhoun College that showed enslaved people coming in from the cotton fields. There’s 2015, and all of the unrest on campus as students of color called people out for wearing blackface or Indian dress as Halloween costumes—and in return they were called “snowflakes” for being “overly sensitive.” There are the recent petitions from students of the medical school and the School of Nursing, in which they asked to be seen, to have their humanity acknowledged, and not to be treated as if they were different but to be treated like their white peers.

But there’s a New Haven teacher named Nataliya Braginsky—who recently won a Teacher of the Year award from the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History—whose students have created podcasts and walking tours about New Haven history. There’s something so honest that comes across when you take the tours and you listen to the students talk about their experience of New Haven and how they were able to learn this history and to bring it forward. Can we find creative ways to bring this history to the community? Can we have dialogues and interactions among New Haveners, and create public art in all kinds of spaces, all over the city, that will engage many different groups of people and draw them into a discussion about this history?

Think of the Witness Stones Project, founded by Dennis Culliton. I worked on a project with Dennis at the Pardee-Morris House in New Haven, in June of this year. Along with young people from the Cold Spring School and the Foote School, we put in stones—markers—with information about the enslaved people who had lived there. Can we put similar markers into public spaces in New Haven, inscribed with information that invites anybody to stop and read at any time of day? It would be wonderful to see Witness Stones on Chapel Street with information about the history of Connecticut Hall.

Recently I took a walk through Grove Street Cemetery. I visited the graves of Sylvia Ardyn Boone ’79PhD and John Blassingame ’71PhD and Benoit Mandelbrot—Mandelbrot because he created a fractal mathematics that looks like an explosion and that grows bigger, and Blassingame and Boone because I know that if they were here today, they would be saying, “Make this history known. Bring it to a place where anyone in the world can google Alexander Du Bois or Charles McLinn and find out about their history in this city. Bring it. Make it visible. Make the truth and reconciliation that all of us need in order to heal.”

It’s overdue. And it’s time.

Adrienne Joy Burns is a physician assistant at the Yale Cancer Center.

loading

loading