Courtesy the Paul Rudolph Estate and the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture

Architect Paul Rudolph, at the peak of his 1960s fame, is the subject of an exhibition on view now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

View full image

Courtesy the Paul Rudolph Estate and the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture

Architect Paul Rudolph, at the peak of his 1960s fame, is the subject of an exhibition on view now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives

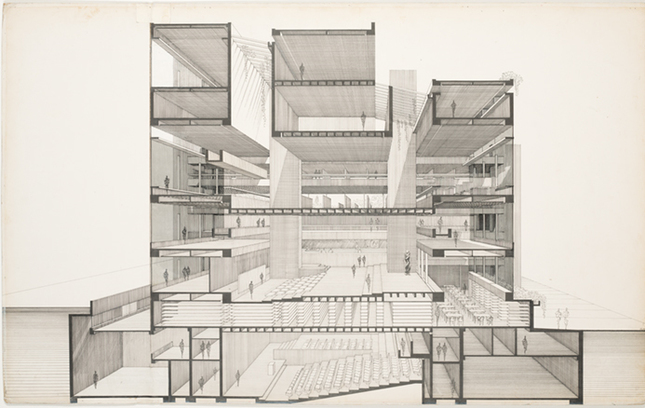

A cross-section of Rudolph’s Yale Art and Architecture Building displays the building’s spatial complexity.

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives

A cross-section of Rudolph’s Yale Art and Architecture Building displays the building’s spatial complexity.

View full image

The professional journal Progressive Architecture, which usually preferred putting buildings on its cover rather than people, gave Rudolph celebrity treatment, combining his face and the building’s on its January 1964 cover.

View full image

The professional journal Progressive Architecture, which usually preferred putting buildings on its cover rather than people, gave Rudolph celebrity treatment, combining his face and the building’s on its January 1964 cover.

View full image

© Ezra Stoller/Rsto, Yossi Milo Gallery

In a decade, Rudolph’s work evolved from the lightweight steel of the 1952 Walker Guest House in Sanibel, Florida . . .

View full image

© Ezra Stoller/Rsto, Yossi Milo Gallery

In a decade, Rudolph’s work evolved from the lightweight steel of the 1952 Walker Guest House in Sanibel, Florida . . .

View full image

Ezra Stoller/Esto, Yossi Milo Gallery

. . . to the heavy, sculpted concrete of the 1961 Temple Street Garage in New Haven.

View full image

Ezra Stoller/Esto, Yossi Milo Gallery

. . . to the heavy, sculpted concrete of the 1961 Temple Street Garage in New Haven.

View full image

“I suppose all architecture has to die before it can touch the historical imagination,” wrote the great architecture historian John Summerson, and no body of work proves his point better than that of Paul Rudolph, whose difficult, harshly beautiful buildings, like the one he created for Yale’s art and architecture schools in 1963, were the talk of the architecture world when they were new, and then fell so far out of fashion that they, and their creator, all but disappeared from the architectural canon. For years, it was hard to hear anybody say a good word about Rudolph, an irascible man whose personality could seem as prickly as his buildings. His determination to produce his own brand of highly sculptural modernism rocketed him to fame in the 1950s and 1960s, but by the 1980s it put him increasingly at odds with almost everything that architecture seemed to be about. Rudolph headed the Yale School of Architecture from 1958 until 1965, and when he left New Haven to practice architecture in New York he stubbornly went on designing buildings that were assertively, even aggressively, modern at a time when many other architects were moving toward a more modest, quirkily decorative architecture that took its cues from the past. Rudolph, who died in 1997, was delivering brutalism when architecture was pivoting toward postmodernism, and he paid a price.

Well, that was then, and this is now, and Rudolph has now receded far enough into history to be rediscovered. If his architecture died when his reputation declined—not just in Summerson’s sense but in a sadly literal way, since an unusual number of Rudolph’s buildings have been demolished—it has been reviving, slowly but steadily. Rudolph’s restoration has come too late for the architect to take pleasure in it himself, but his reputation continues to rise, proving Summerson right. Last fall the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened a retrospective exhibition of his work, underscoring the extent to which Rudolph now is seen more than ever as a critical part of twentieth-century architectural history.

More powerfully, and more poignantly, the Yale Art and Architecture building tells the story of the arc of Rudolph’s reputation. Rudolph had a complex relationship to Yale, an institution that celebrated him, recruited him to head its architecture program before he was 40, and gave him several architectural commissions in addition to the architecture school—and then, he felt, turned its back on him. The Yale Art and Architecture Building was on the cover of every architecture magazine when it opened, not just the building of the year but the building of the decade, the 1960s equivalent of Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. More than two thousand people attended its dedication, and it seemed as if Rudolph had singlehandedly shifted the image of Yale from a campus of comfortably traditional Gothic buildings to a place of exciting, cutting-edge architecture. (I have a distinct memory as a young teenager enthusiastic about architecture of seeing the cover of Progressive Architecture magazine, which juxtaposed Rudolph’s face over the rough-hewn concrete façade of the building. It was one of the reasons I wanted to go to Yale.)

Less than a decade later, the building, beset with functional problems and disdained by students, faculty, and even by Rudolph’s successor at Yale, Charles Moore, was badly damaged in a fire. To Moore, the Art and Architecture Building contained only negative lessons for students. After the fire, he had no interest in restoring the building to its original state, and opted instead for an inexpensive, quick renovation that compromised many of the intricate multilevel spaces and destroyed many of the elements of transparency and spatial connection that were fundamental to Rudolph’s architecture.

But even before the fire, Moore had made no secret of his differences with Rudolph and seemed to encourage students to see the architecture building not as the carefully crafted, precise work of sculptural space Rudolph had intended it to be but as a series of loft spaces that could be altered any which way. Like many students in the 1960s, Moore saw the monumentality of Rudolph’s building not as a pure exercise in form and spacemaking but as the embodiment of an overbearing arrogance that, at least in the tense political climate of the 1960s, seemed to invoke the very qualities that the counterculture was trying to fight. It was the architecture of the establishment, created by an architect who positioned himself as the heroic master builder and all-knowing creator of highly individualistic buildings. To many students back then, the architect’s message seemed to be that if you did not find his building easy to live with, then you, and not the architecture, must be at fault.

Rudolph’s attitude was never so closed-minded as that, but his passion for experimentation made him easy to caricature. After the fire, he became increasingly embittered and would not talk about the building in public. He only rarely returned to New Haven after he moved his practice to New York, and when he came back to Yale in 1974 to lecture about his work, the Art and Architecture Building was the elephant in the room; he did not once mention it.

It would take another 40 years, but in 2008, under the direction of Robert A. M. Stern ’65MArch, a former Rudolph student who became dean of the Yale School of Architecture in 1998, the Art and Architecture Building was magnificently restored by the architect Charles Gwathmey ’62MArch, another former Rudolph student. And then, almost as an act of repentance, the building was renamed Paul Rudolph Hall, thanks to the generosity of the Bass family, longtime donors to Yale and, more significantly, unwavering admirers of the architect. (Sid Bass ’65 had commissioned Rudolph to design a house in Fort Worth in 1970 that remains one of the architect’s finest works, and Sid Bass and his brother Ed Bass ’67 hired Rudolph to design a pair of office towers in downtown Fort Worth in 1978, when few American developers wanted to have anything to do with him.)

Stern’s determination to restore the building and the willingness of the Bass family to allow it to carry the architect’s name rather than their own represented more than Yale’s change of heart regarding Rudolph. It symbolized the beginning of the Rudolph revival that has brought an equally conscientious restoration of the library on Rudolph’s 1963–72 campus for the Southeastern Massachusetts Technological Institute in Dartmouth, Massachusetts, in 2012 by designLAB, and later the restoration by Sasaki Associates and Finegold Alexander of another portion of that campus. In 2019 one of Rudolph’s most famous early projects, the Walker Guest House of 1953 on the west coast of Florida, was auctioned by Sotheby’s as a work of art. And by this year the revival had become sufficiently robust to inspire the Metropolitan Museum exhibition, an honor that the Met has never given to any of the architects whose work shunted Rudolph’s aside during the years that he was out of fashion. (The exhibition, Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph, will be on view through March 16.)

What does the revival of interest in Rudolph mean? Here again, Summerson had it right. It is not so much that architecture has reverted to Rudolph’s way of seeing the world as it is about the passage of time. What once seemed overly bold now feels familiar, if not always comfortable, and Paul Rudolph’s entire oeuvre has taken on a kind of patina. Paul Rudolph Hall is now older not only than the students who study in it, but most of the faculty who teach in it. With the passage of more than half a century, it is easier to appreciate Rudolph’s deeply earnest belief in the power of pure architectural form and space, especially in an age in which building is all too often quick and facile. Now, Rudolph evokes the idealism of the 1960s as much, if not more, than the arrogance of power that the decade also represented.

Rudolph was too much of a genuine teacher, and too interested in thinking about how people live and how cities work, to be really like Howard Roark, the absurdly arrogant architect-hero of Ayn Rand’s novel The Fountainhead—that, I think, is the real point. Rudolph had one of the most fertile architectural imaginations of modern times, and I think time has allowed us to understand that his architectural ideas were far more complex, and more subtle, than the simplistic figure he appeared to be for so many years. The postmodern movement in architecture needed a foil, and Rudolph provided it.

There is no small irony to the way in which Rudolph was rejected as a figure of the establishment, because he was, to the end, a radical, and obsessed with experimentation. He used new materials; he envisioned new ways of thinking about space and technology and popular culture and mass production and urbanism and the relationships between surface decoration and architectural space. He was never indifferent to history; indeed, part of the power of Paul Rudolph Hall at Yale comes from the way in which the architect integrated aspects of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Building in Buffalo and Le Corbusier’s monastery at La Tourette, France, two great but very different twentieth-century masterpieces, and wove them together into a composition that was entirely new and entirely his own—a composition that, it should be said, also weaves its way deftly into the complex New Haven cityscape. When we look back at his work now, to invoke Summerson one more time, it is clear that Paul Rudolph does not so much touch the historical imagination as ignite it, making history richer still.

loading

loading

1 comment

-

George Huthsteiner '74 TD, 11:57am December 29 2024 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.<> I attended Paul Rudolph's lecture at the Yale Art Gallery in April 1974. I could feel the acrimony between Rudolph and his critics hanging in the air.