loading

loading

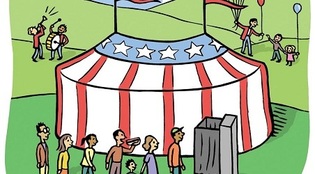

Findings“Party” politicsCould making Election Day fun increase turnout?  Gregory NemecView full imageAt election time, political organizations and candidates inundate voters with appeals. Yet typical turnout rates remain woefully low. A recent study suggests that turning Election Day into a party might give turnout a slight boost. In the nineteenth century, voter turnout regularly topped 70 percent - despite the long horse-and-buggy journeys many people faced. But voters arrived expecting to do more than just cast their ballots. According to Yale political scientist Donald P. Green, an authority on voter turnout, Election Day was a festival in which voters enjoyed "booze, music, and raucous activities that went on all day." But Progressive Era reforms, which introduced the secret ballot and curtailed vote buying, also succeeded in banishing the fun. Voting now takes place, says Green, in "a morgue-like atmosphere." Could reconnecting Election Day to fun - legal, of course - increase turnout? In 2005 and 2006, Green and colleagues threw Election Day parties, with free music, food, and (nonalcoholic) drinks, near polling stations in 14 randomly selected precincts. For controls, Green chose precincts nearby that had comparable demographics and political issues. The "Election Day Festivals" were well publicized. On voting day, Green recalls, "The sounds of music and smell of barbeque wafted through the neighborhood and attracted people." All partygoers were encouraged to vote. The results, published in October in the journal PS: Political Science & Politics, showed that for hot electoral races, the festivals increased expected turnout by nearly 10 percent. The average increase was only 2.5 percent - but costly direct mail and telephone campaigns typically aim to raise turnout by less than 1 percent. "To throw a party for a couple thousand dollars and boost turnout by that much is a bargain," says Green.

The comment period has expired.

|

|