loading

loading

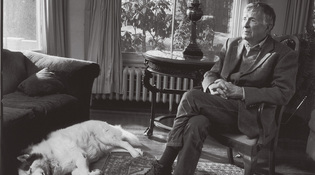

featuresThe patriarchVincent Scully is controversial, combative, the consummate insider but a fighter by nature. He is one of the most influential voices in architecture today -- and maybe the greatest lecturer Yale has ever seen. For Richard Conniff ’73, Scully's class was a formative introduction to how the visual world shapes behavior.  Portrait by Mary Ellen MarkVincent Scully at home in New Haven with dog, Aldo. He grew up in New Haven, halfway between the Yale campus and the Bowl, and never considered that he would go anywhere but Yale. View full imageAt 11:35 on a Monday morning, Vincent Scully walks to the lectern and glances at his watch. As always at the start of a talk, he's a little tense, like an actor wound up before a play. "Ladies and gentlemen," he begins, "you will remember the last time I talked to you about . . ." The lights of the lecture hall go dark and slides appear on the big screen behind him. His voice is soft and hesitant at first, probing for the way forward. He does not use notes or deliver quite the same lecture twice, even after 60 years. But the words soon catch on the flow of images, and that voice, gentle one moment, all gravel and tumult the next, begins to draw his audience with him. Names and dates to be memorized do not figure largely in what follows. Scully's goal is to open his students' eyes, by showing them how he sees and thus how they can begin to see for themselves. So it's not just an Ionic column, mid-sixth century B.C., up there on the screen. Nor do the volutes of the capital look to him, as others have proposed, like the ringlets of a woman's hair. Instead, Scully ’40, ’49PhD, points out how the slender, fluted columns rise like jets of water, lifting the broad horizontal entablature of the temple, then flowing out to either side. "You can make that shape with a paddle in the water," he says, of the scrolls on the capital. "It's geometric. It's hydraulic." He stands off to one side of the stage, the smudge of reflected light from the lectern making a ghostly presence of his reddened face and the pale double curve of the eyebrows. He cants himself toward the slides, and his hands reach out, turning and undulating, as if he means to conjure the image to life on the stage. When he shows the huge choir window behind the altar at Chartres, he remarks that you have to climb uphill to the cathedral, and still seem to be climbing once inside. "You get the feeling there's a great tide coming. If you've ever rowed, and the tide changes . . ." Here he reaches out with both hands for imaginary oars and lays his back into it, as if toward the heavenly light behind the behind the altar. The New Yorker once ran a profile of Scully, which ended with a scene of him rowing his Gloucester Gull out into the wild winter seas of Long Island Sound. He was roaring Homer in the original Greek, as the waves came rumbling "polyphloisboio" toward the bow, and then went sighing "thalasses, thalas-ses" beneath the boat. It was a portrait of the art historian as an old man, defiant, a little crazy, and clearly on the shortlist for the afterlife. But 28 years later, Scully is still out rowing in winter. (He uses a heavier boat now, a weathered old Bank dory evocative of that other Homer, Winslow.) At 87, he also still teaches the course for which he is famous, as much as for his 20 books, or for the criticism that has made him one of the most influential voices in modern architecture. For generations of Yale students in History of Art 112a, Scully's voice rising from the front of a darkened auditorium has been their first real experience of art and architecture. It has always been a form of theater, one man on a stage serving up careful analysis, unabashed emotion, and an astonishing breadth of literary, mythological, and intellectual associations. The news of the day has often gotten mixed in, linking Picasso's Guernica to the My Lai massacre, propaganda sculpted on the breastplate of Augustus to an American president boasting "Mission Accomplished." ("Works of art stay the same," Scully says, "but meanings drain in and out of them according to the experience of a generation.") In Scully's prime, his theater was physical, too. He depended on an audiovisual assistant working as many as seven slide projectors at once, and he liked to prowl hungrily beneath the images. "Focus!" he'd cry. "Would you please get the focus? You're making it worse. Focus, please." Sometimes he rapped on the stage with his pointer to call up a new slide, and now and then, carried away with a thought, he flailed at an image on the screen until a snowfall of reflective particles came drifting down. Once, driving home some emphatic idea about modern architecture, Scully ripped the screen with his pointer. He didn't comment until several slides later, says Ned Cooke ’77, a student in that class and now a professor in the art history department. Then he deftly folded the rip into a discussion of surface and skin in a house by Le Corbusier. Part of the Scully legend is that he once got so carried away during a lecture about Frank Lloyd Wright that he fell off the stage, and climbed back up, bleeding but still on topic, to wild cheering from his students. ("I never really fell," he confides now. "I miscalculated, and jumped.") He still has that performer's instinct for the moment, making a strength even of his age. When the temple at Deir el-Bahri goes up on the screen, he begins to describe "the 18th-dynasty queen named . . ." but then stops and says, unembarrassed, "Ah, I'm so sorry. I don't know." He walks back to the lectern. "You will tell me the name, you know it." A few voices call back to him, and he catches it. "Hatshepsut. I'm so sorry . . . one of those things." Smiling now, he says, "You will have to carry me out in a moment." The audience laughs, and he returns to his topic.

|

|