loading

loading

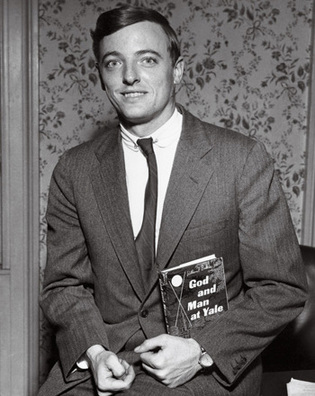

featuresWilliam F. Buckley: the founderAt Buckley’s Yale, Skull and Bones was still the apex of campus life, the Yale Daily News board chugged martinis at Mory’s, and, as a new-moneyed Catholic, Buckley fit in and yet didn’t fit in. But he made the place his own, and there he found his voice as a conservative. Sam Tanenhaus ’78MA is the editor of the Week In Review and Book Review sections of the New York Times. He is writing a biography of William F. Buckley.  CorbisThe newly published author. "Sonorous pretensions notwithstanding, Yale (and my guess is most other colleges and universities) does subscribe to an orthodoxy," he wrote. View full imageIn September 1946, when William F. Buckley Jr., 20 years old and freshly discharged from the U.S. Army, arrived in New Haven, he entered a university undergoing a profound transformation. Owing to the G.I. Bill, the Class of 1950 was by far the largest in Yale history, its 1,800 members more than double the prewar average. The Old Campus, built to accommodate 850 people, now held 1,200. Others bunked as far away as Allingtown, three miles from New Haven. Vestiges of wartime "processing" remained. Buckley and his classmates stood for hours on registration lines and began the term eating meatless meals because of job actions by strikers and meatpackers and delays from the Office of Price Administration in Washington. These were inconveniences, not hardships. Most members of the Class of 1950 had put up with a great deal more. Two-thirds were veterans; hundreds had seen action in Europe or the Pacific. "They were men," recalled Raymond Price Jr. ’51, the future presidential speechwriter who came to Yale in 1947, at age 17, and observed the vets with awe. "They were serious. They had a purpose." None more so than Buckley. "He was the most impressive figure, most visible figure in [our] class," remembered the almost equally driven Tom Guinzburg ’50, one of Buckley's closest college friends—his coeditor on the Daily News, fellow Bonesman, later his occasional book publisher. "There were some very strong and visible, successful undergraduates. But Bill was someone to be reckoned with immediately. He was taking initiatives as soon as he got to Yale. He arrived in full stride." Or full sprint. Others had ambitions. Buckley came with a mission: to advance the conservative ideology he had grown up with and taken with him to boarding school in Millbrook, New York, and then to the army. On the surface, Yale was not in need of conservative indoctrination. Fully 50 percent of its undergraduates identified themselves as Republicans in a campus poll published in Buckley's sophomore year, as opposed to 17 percent Democrats and 3 percent Socialists. But to Buckley, majority views, expressed passively in a poll, mattered less than the tenor of ideological debate, and there liberals and even the few campus leftists seemed to hold the advantage. "The so-called conservative, uncomfortably disdainful of controversy, seldom has the energy to fight his battles, while the radical, so often a member of the minority, exerts disproportionate influence because of his dedication to his cause," he would observe in God and Man at Yale, the book that stands today as the founding text of the modern conservative movement. It was a movement whose contradictory impulses (libertarian yet authoritarian, populist yet elitist) reflected Buckley's own, for he was himself a kind of radical, in his own way at war with Yale's most hallowed conventions. Outwardly he exhibited many familiar attributes of Old Blue: the family fortune supported by Wall Street; the Yale-educated kin (three of his brothers); the country estate (Great Elm, forty-seven rolling acres in the Berkshire foothills, with stables, tennis courts, and a swimming pool). But Buckley's Irish and Swiss roots, his Catholicism, his family's new money, his diploma from an upstart Dutchess County prep school placed him firmly outside Yale's inner circle of upper-class, high-Protestant privilege. Publicly, Buckley defended the institution's "right" to practice discrimination in admissions (by unwritten policy, Catholics and Jews were limited alike to 13 percent of each incoming class) and in its social clubs. But privately he combated prejudice. When Guinzburg was passed over by the Fence Club "because they didn't like the sound of my name"—that is, because Guinzburg was Jewish—Buckley pressured the club to change its rules. "There were guys in the Fence Club who never ate a meal in the dining hall their entire undergraduate lives," Guinzburg remembered. "They had allowances, trust funds." They lived just as their fathers, also Yalies, had done 20 and 30 years before. But not Buckley. Like so many others, he coveted social success and diligently pursued campus prizes: chairmanship of the News, admittance to Bones. (He won the place of honor in his year, as the last man tapped.) But he did so in the belief that he represented something new at Yale, an emerging meritocracy. While branded a "black reactionary," opposed to liberalism in all its forms, he was most intent on battling "liberal orthodoxy," the presumption that liberal ideas were inherently superior to conservative ones and liberal attitudes intrinsically virtuous. There are undertones of Everyman protest in Buckley's unmasking, in God and Man at Yale, of "one of the most extraordinary incongruities of our time: the institution that derives its moral and financial support from Christian individualists and then addresses itself to the task of persuading the sons of those supporters to be atheistic socialists."

|

|