loading

loading

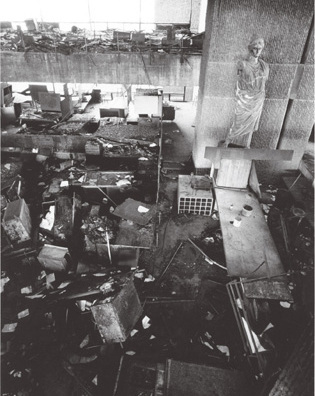

Love it? Hate it? Or both? Manuscripts & ArchivesThe A&A was damaged in a fire of unknown origin in 1969. View full imageOver time, the once-revolutionary building became the target of a counter-revolt,which deemed its spatial gymnastics and hard-edged materials oppressive -- even a symbol of the national hubris associated with the war in Vietnam. By June 14, 1969, when a fire of suspicious origin severely damaged the A&A, it was widely interpreted as a violent form of architectural critique. "I just said that the building was so guilty that it burst into flames all by itself," adjunct professor Turner Brooks ’65, ’70MArch, told me. A year later, during New Haven's infamous Black Panther trial, Brooks watched as the National Guard cordoned off the streets in front of the building: "Looming behind them was the great charred hulk of the A&A, which represented everything that was wrong about everything." The chair who followed Rudolph, postmodernist Charles Moore, was no fan of his predecessor's heroic vision -- and he was even less inclined to preserve it. In the years after the fire, partitions carved up the once-open studio spaces. The growing art and architecture schools condoned other unsympathetic changes in order to squeeze usable space out of the building. The Yale Art Gallery took back the statue of Minerva after the fire (and after students painted her toenails). By the time I arrived in 1982, the A&A was a ruin before its time, but with none of the romantic aura of a decaying monument on some English gentleman's country estate. But during the deanship of Chicago architect Thomas Beeby ’65MArch, who headed the school of architecture from 1985 to 1992, a reaction set in against postmodernism and its superficial decorative effects. "When I got there, the students actually loved the building," Beeby told me, although, he was quick to add: "One time they tore a ceiling out because it was so hot in there." With money flowing freely after the boom years of the late 1990s, and with the School of Art moving to a home of its own across Chapel Street in 2000, the stage was set to remake the A&A. It had managed to last long enough for people to appreciate it again. In restoring the A&A, Gwathmey was performing a far more complicated task than remaking a single building. He and his New York firm, Gwathmey Siegel & Associates, were wrestling with an extremely difficult design issue: how do you preserve a singular landmark and add on to it at the same time? The question had a special master-student tension, because Gwathmey worked for Rudolph when he was a student. Rudolph, who died in 1997, had always envisioned expanding the A&A, Gwathmey and Stern told me. Though he left no precise instructions, they said, his idea was to break through the stair tower on the building's north side and form a courtyard linked by the A&A on one side and the new building on the other. That is essentially what Gwathmey has done, though his "courtyard" is not an outdoor space but a portion of the new Robert B. Haas Family Arts Library, which brings together Yale's collections in art, architecture, and drama. The library's "Great Hall" is topped by domed skylights that draw natural light into the multilevel atrium, where students curl up in bright orange Womb chairs designed by Eero Saarinen ’34BFA. For all its fidelity to Rudolph's plan, however, the seven-story history of art building, which houses lecture halls and classrooms, faculty offices, outdoor terraces, and a street-level cafe, is hardly self-effacing. Instead of quietly taking its place alongside the A&A, it seeks to strike up a sophisticated conversation with Rudolph's building, echoing it in some ways while departing from it in others. From York Street, the height and mass of the new building appear to match the old one. But its diagonal and curving geometry departs from Rudolph's right angles, as do its exterior materials, which are panels of zinc and limestone instead of corrugated concrete. Responding to the history of art department's request for an architectural identity, Gwathmey aimed for the building to have its own iconic presence.

|

|