loading

loading

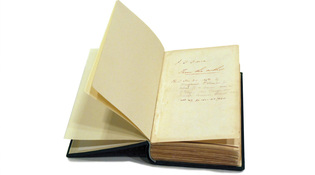

Arts & CultureObject lessonThe book that started it all Leo J. Hickey, professor of geology and curator op paleobotany at the Peabody Museum, specializes in the evolutionary history of flowering plants.  Mark Zurolo ’01MFACharles Darwin sent this personally inscribed first edition of Origin of Species (1859) to Yale geologist James Dwight Dana. Beneath Darwin's "From the author," chemist Benjamin Silliman Jr. has noted, "Recd Dec. 21, 1859 . . . when JD Dana was in Italy." Dana was recovering there from a breakdown, and Darwin later wrote him, "You must not think of reading my book for a long time, as my friends tell me it is tough reading." View full imageThis year marks both the bicentennial of Charles Darwin's birth and the sesquicentennial of the first edition of his On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. Yale is fortunate to own three first editions; only 1,250 volumes were printed. But surely one of the university's greatest material treasures is this copy, inscribed by the author himself to one of the most eminent scientists of the time, James Dwight Dana, Class of 1833, professor of natural history and geology. The full text and even a scan of this edition are readily accessible online, and nothing about the actual book, from its small size and slightly yellowed pages to its embossed chrome-green covers and Victorian stampings, seems out of the ordinary. When I saw it, it was resting in a foam cradle on a table in the Beinecke reading room, having been borne there from the sanctum by an acolyte librarian. It looked, if anything, curiously fragile. And so I was surprised at the strength of my feelings when I opened its cover to see Darwin's handwriting on one of the blank pages in the front. For this is the book that shook the world like none before it, with reverberations that continue to the present day. At one stroke it explained the unity yet myriad diversity of the organic world and substituted the vision of a self-perfecting system for that of a static hierarchy whose every action was the result of the constant, willful intervention of an all-knowing power. With Darwin's insight that it was from death and the struggle for existence that more perfected beings arose, the book resolved the age-old dilemma of good and evil and paradoxically absolved God from willing evil on his creation. From the very beginning, neither Darwin nor his audience had any doubts about the revolutionary nature of this work. Indeed, its implications so troubled Darwin that he gave subsequent editions a slightly more theistic tone. Yet his theory, expressed in clear and majestic prose, would stand the test of skeptical evaluation and transform our worldview. The true power of this little book comes into full focus in its final sentences:

The comment period has expired.

|

|