loading

loading

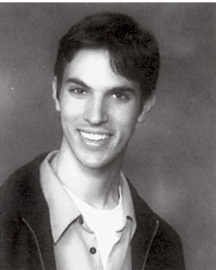

featuresBanality as a giftMemoirs from the evolution Ari Shapiro ’00 is the justice correspondent for National Public Radio's Washington Desk.  2000 Yale BannerAri Shapiro in his senior yearbook photo. View full imageWhen I was a young teenager in Portland, Oregon, I read Paul Monette's memoir, Becoming a Man. It chronicled Monette's life as a gay man, including his time at Yale (Class of ’67). I didn't read the book as an aspiring Yalie; I read it as someone trying to figure out what my life would be like if I decided to come out of the closet. As best I could tell from the book, if I decided to come out of the closet my life would be pretty miserable. Terrible relationships, blistering homophobia, and deep self-loathing. Several years later, I read another book about a gay man who'd attended Yale in an earlier generation: Calvin Trillin's Remembering Denny. Trillin's eulogy for his classmate Denny Hansen ’57 left me with the impression that even if my life as a gay man involved tremendous success and popularity, it would still lack happiness. Hansen was a golden child, a Rhodes scholar, and a member of Scroll and Key. He committed suicide in middle age. With Paul Monette and Denny Hansen as prologue, the banality of what I am about to say is almost embarrassing. I married my college boyfriend. I realize this is somewhat unremarkable, as women have been marrying their college boyfriends for decades. I think, however, that men marrying their college boyfriends is not something Paul Monette or Denny Hansen would have envisioned. For me, the significance of my marriage is not so much the legality of the thing. Our 2004 wedding at San Francisco City Hall was annulled by California's Supreme Court, and although our childhood rabbis jointly performed a religious ceremony the following year for family and friends, we have yet to tie the knot a third time to make it legal. Gay marriage is a fraught political debate, and as a reporter I try not to participate in political debates. If I could get married without making a political statement, I would. That said, I met my future husband the last week of my freshman year. We were married seven years later. Today we have a house in Washington, DC, together. I cook, he cleans. Our parents come to our Passover seders. As I said, it's all incredibly banal. And I realize that the banality of my Yale experience in this respect -- and the banality of my life since then in many respects -- is only possible because of the generations of gay Yalies (and non-Yalies) who lived far more difficult lives. Because of them, I have the privilege to choose not to be an activist. I don't need to worry that I will lose my job if people find out who I am, much less fear for my physical safety or that of my husband. When I think about my "gay life at Yale," the best I can come up with is -- I met my future husband. I don't think I could ever write a memoir of my life, and I don't think anyone would ever want to read one. It would simply be too boring. And for that, I owe a debt to people like Paul Monette and Denny Hansen.

The comment period has expired.

|

|