loading

loading

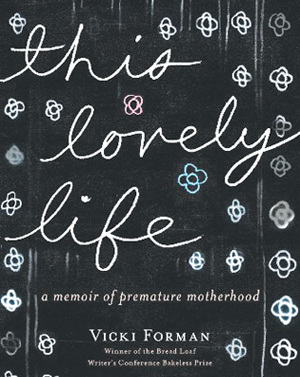

Arts & CultureBorn too soonBook review Sue Halpern ’77 is the author of two books of fiction and three of nonfiction, most recently Can't Remember What I Forgot: The Good News From the Front Line of Memory Research.  View full imageThe lessons of This Lovely Life -- both the one we all have been given as well as Vicki Forman's indelible memoir -- often are not the lessons we expect. You get pregnant, for instance, as Forman did, and begin to envision a future for the baby you will have. You make certain signal assumptions, even though this person, when it is born, will be a stranger. You paint the walls, collect toys, hew to the advice of books with titles like What to Expect When You're Expecting. Ontology may not recapitulate phylogeny, but for most of us, until we are told otherwise, there's a largely unspoken belief that our child's development will reprise our own. So it was for Forman and her husband, Cliff Kamida, who were living an ordinary, pleasant life in Southern California with their three-year-old daughter when Forman learned she was carrying twins. Conception the second time around had been difficult, and had been preceded by a number of miscarriages, but until Forman went into labor prematurely and delivered the babies at 23 weeks, it had been a largely uneventful, predictable, pregnancy. Twenty-three weeks is more than four months shy of the average gestational age. (Full-term is 40 weeks.) It's the cliff-edge of viability; abortions may still be legal. At 23 weeks the eyes are fused shut and the lungs are not fully formed. Unassisted breathing is rare. Until recently, a baby born at 23 weeks had no chance of survival, but advances in medical technology mean that that is no longer always the case. Even so, according to a study of preemies at Brigham and Women's Hospital published in 2001, a year after Vicki Forman went into premature labor, “no neonates [born at 23 weeks] survived free of substantial morbidity.” Morbidity is a neutered term. Substitute instead: brain bleeds (and subsequent mental retardation), chronic lung disease and respiratory distress syndrome, impaired vision and blindness, epilepsy, cerebral palsy. Forman, the daughter of a psychiatrist whose specialty was treating children with disabilities, knew this better than most. When it became clear that she was in labor, she instructed the doctors to let nature take its course, warning them off any interventions, telling them that there were to be no heroic measures to keep these babies alive. What she didn't know was while some hospitals have guidelines that preclude intensive care for babies born before 25 weeks, her hospital had no rules governing how care was to be allocated. That decision, it seemed, was left to whoever happened to be on call. “Let them go,” she instructed the neonatologist, only to be told, “What you're asking, I cannot do.” And so, against her wishes, as soon as the babies were delivered -- a girl named Ellie who weighed 1 pound, 7 ounces, and a 1 pound, 3 ounce boy called Evan -- they were hooked up to monitors, IV drips, and oxygen. The Do Not Resuscitate order Forman and her husband requested might as well have been written in invisible ink. Ellie survived four days. Evan held on against all odds. He was blind despite numerous operations to restore his sight, had a feeding tube sewn into his stomach, developed cluster seizures that caused his body to stiffen and flail many times a day, did not walk till he was five, could not speak. Taking care of him became Forman's full-time occupation. The endless hospitalizations, the trips to this specialist and that surgeon, the hour-by-hour schedule of medications, the syringes, the feeding pump that would sometimes dislodge in the middle of the night and fill Evan's crib with formula, the oxygen apparatus that had to be taped to his face. The heroic measures offered up by the physicians to keep Evan alive were nothing compared with those of Forman and her husband as they labored, for real, to give him a life. Not that Forman makes this claim herself. This is a book of revelation, of a woman coming to terms with herself, and it is painfully, unsentimentally honest, without a speck of vanity. Forman was angry, exhausted, crazed, medicated, fierce, intemperate. Taking care of a gravely ill, disabled baby was not what she was expecting when she was expecting: this was not supposed to be her life. She lit candles, made bargains, but this new life didn't go away. It was hers, just as Evan was hers. “Eventually,” she writes, “I found a way to go beyond the words [cerebral palsy, mental retardation, blindness, congenital heart disease, seizure disorder], the diagnoses, the shadows of uncertainty they cast. Eventually I got to a place where I could see Evan as not just a boy with problems -- or words that described those problems -- and not just a kid who might not walk or talk, and who obviously couldn't see. Instead, I saw my son. His beautiful smile, his sense of humor, and his delight in the world.” In some ways, Evan got better. His seizures eventually disappeared. He no longer needed a feeding tube. At three he learned to crawl. He took steps at five, and by six he was walking. When he died, six days before his eighth birthday, it was sudden, without warning, and not from his congenital heart defect, but from a gastrointestinal blockage caused by scar tissue that had built up during all those years in which he'd been fed through a tube. He had been alive, and then he was gone, and nothing Vicki Forman learned about love and patience and expectations and the inadequacy of the word “disability” went with him. This Lovely Life is her story, really, not his. It's her serrated journey from grief to accommodation to forgiveness to acceptance. So when she asks herself the question that lurks in the margins here -- knowing the doctors' eagerness “to prove all that medical science could do to save one-pound babies” while “on the other side of that accomplishment [doing so little] to help,” but, even so, having known and deeply loved her son, would she still have insisted that the doctors let her babies die? -- she cannot say. She just doesn't know. In her ambivalence is her eloquence.

The comment period has expired.

|

|