loading

loading

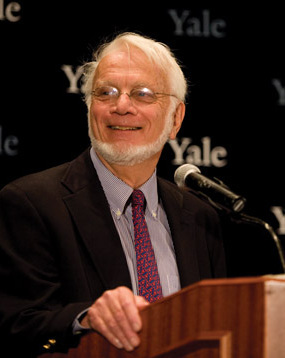

Light & VerityStockholm calls for Yale professor Julie BrownView full imageThe phone rang just before 5:30 a.m. on Tuesday, October 7, waking two Sterling Professors of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry at their home in Branford. Joan Steitz answered, but the caller, who had a European accent, asked for her husband. “Tom,” she said, “it’s for you.” It could have gone either way: both Tom and Joan Steitz have been mentioned in recent years as potential Nobel laureates in chemistry. But it was Tom Steitz who was told that he'd be sharing the $1.4 million 2009 prize with Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, a structural biologist at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, England; and with Ada E. Yonath, a crystallographer at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel. Steitz, who joined the Yale faculty in 1970, is the second Nobel laureate among current Yale faculty members. Sidney Altman, the Sterling Professor of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology and Chemistry, shared the prize for chemistry in 1989. According to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Steitz and his fellow scientists were honored for “studies of one of life’s core processes: the ribosome’s translation of DNA information into life.” At a press conference after the announcement, Steitz explained that the ribosome was “a very large and complex machine found inside each cell that makes proteins.” The three new Nobelists, working independently on different parts of the ribosome, used a technique known as x-ray crystallography to map the manufacturing process at the atomic level. “It was like climbing Mount Everest,” said Steitz. “We knew it was doable in principle, but we didn't know how we'd get there.” The work has led to a New Haven-based biotechnology company called Rib-X Pharmaceuticals, which Steitz co-founded in 2001 with Sterling Professor of Chemistry Peter Moore ’61. Rib-X now has several prospective antibiotics, designed to target the ribosome, in clinical trials. For Steitz, the award marks the latest step in what he called a “quest.” As a student in the 1960s, Steitz became fascinated with the DNA-to-protein puzzle, the details of which were beginning to be understood. At Yale, he and Moore developed the techniques necessary to zero in on the ribosome, the cellular body in which the assembly process, guided by an information-carrying molecule called RNA, takes place. Steitz’s lab tackled one of the two subunits of the ribosome—the part that does the actual protein synthesis—while Yonath and Ramakrishnan (who began his career as a post-doc with Moore during 1978–82) worked on the subunit that makes sure the synthesis is accurate. In 2000, the scientists finished crafting intricate, atomic-level portraits of actual ribosome subunits and published the results that the Nobel committee honored this year. “When you look at the pictures, it’s amazing anyone could figure this out,” said Yale president Richard Levin ’74PhD, who was beaming throughout the press conference. “This is the protein machine, the source of life. It’s a fabulous accomplishment.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|