loading

loading

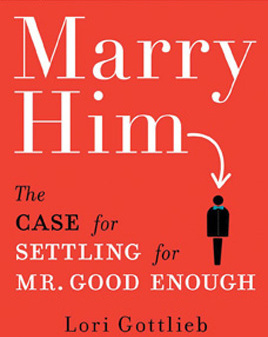

Arts & CultureHe'll DoBook review Nina Shen Rastogi ’02 writes a column for Slate and the Washington Post. She lives with her boyfriend in Brooklyn.  View full imageIn Shakespeare’s As You Like It, the heroine, Rosalind—in her disguise as the young swain Ganymede—offers some friendly advice to a vain shepherdess who has been scorning the affections of a decent bumpkin. “Sell when you can,” she whispers in the country girl’s ear. “You are not for all markets.” “Somehow, post–Jane Austen,” she writes, “it became shameful for a woman to admit how lonely she is.” This is more or less the same advice Lori Gottlieb offers, 400 years later, in her new book Marry Him: The Case for Settling for Mr. Good Enough. Gottlieb would probably be the first to admit that her counsel is not particularly original. After all, she advocates listening to the time-honored wisdom of our mothers, who (per Gottlieb) never expected passion or fireworks or wish fulfillment from their marriages—just solid, decent mates on whose dependability they could build strong families. Your personal reaction to Marry Him will largely be determined by whether that image of married life strikes you as delightful or dismal. Marry Him began life as a much discussed, endlessly forwarded essay in the March 2008 issue of the Atlantic. Gottlieb, a single, never-married mother in her early 40s, wrote of her dawning realization that she was never going to decamp with Prince Charming. He didn’t exist—and besides, even if he did, she now had to deal with the twin problems of a decline in her own “marital value” and the increasingly unfavorable ratio in her age bracket of single men to single, searching women. If she ever wanted to find herself a nice life partner, Gottlieb realized, she had better reexamine her overly picky standards, tout de suite. And if younger women wanted to avoid her fate, she cautioned, they’d do well to drop the attitude that was causing them to pass up perfectly serviceable, less-than-inspiring men—the earlier, the better. In her book, Gottlieb refers to numerous angry letters she received after the article’s publication, chastising her for being so desperate and needy. “Somehow, post–Jane Austen,” she writes, “it became shameful for a woman to admit how lonely she is and how strongly she wants to be part of a traditional family.” That may be so. But I suspect that many readers of the original Atlantic article weren’t so much offended by her honest expression of loneliness as by her sweeping suggestion that all single, heterosexual women shared this consuming desire to be a wife and mother. To those who would deny that a woman who hits 30 and finds herself unmarried “feels panic, occasionally coupled with desperation,” Gottlieb sniped in the essay: “[All] I can say is, if you say you’re not worried, either you’re in denial or you’re lying. In fact, take a good look in the mirror and try to convince yourself that you’re not worried, because you’ll see how silly your face looks when you’re being disingenuous.” Allowing for stylistic hyperbole, this exhortation was not only off-putting (and not particularly sisterly) but also unconvincing. “I’m 40 and perfectly happy,” one might retort, or “I’ve never wanted children,” or even “I’d like to be married, but if he doesn’t rock my socks off, who has the energy for decades of ‘not-too-shabby’?” That, of course, was the sly brilliance of the original essay: it brought out every reader’s inner narcissist. We all loved talking about Gottlieb’s essay because it meant talking about ourselves. Her choice of the word settling—as opposed to accommodating, or accepting, or any of the other, more positive synonyms that more accurately capture the mental shift she advocates—also seems to have been calculated for maximum controversy. In the book, Gottlieb dials back her aggressiveness. Marry Him is less a pro-marriage argument (a tough sell in this age of Sanfords and Gosselins and Woodses) than a guide to “adjusting our expectations in a healthy way” so that readers who want to get married can learn to recognize suitable partners. Reading this expanded version, though, one misses the brio of the original essay. You may not have liked it, but it got your fur up: as a manifesto, it had a brash charisma, if not always rock-solid factual premises. Marry Him the book is simultaneously sketchy and overlong. It’s framed as an intellectual and experimental journey—Gottlieb’s search to discover “why our dating lives might not be going as planned, and what our own roles in that might be.” But it’s a desultory campaign. She talks to many professors and “dating experts,” and an endless parade of “regular people,” and before long the book falls into a lulling rhythm of First I talked to this person, and then I talked to that person, and then I talked to that person. Sources are quoted at length—not always to increased effect—and with too much credulity. Getting through all of Marry Him sometimes feels as tiring as Gottlieb makes dating in your 40s sound. Gottlieb’s personal reward, as she tells it in the book, comes in the form of a short, balding widower with whom she spends two “wonderfully tranquil” months before he moves away to Chicago. “I saw firsthand that I can be attracted to and happy with people I haven’t looked at in the past,” she concludes. Private epiphanies have certainly rested on less, but for the reader, it’s a thin narrative payoff. It’s a shame, because there’s good, eminently reasonable advice to be gleaned from the book. Gottlieb’s message isn’t a facile Pinch your nose and marry that slob before your eggs dry up. Among the key lessons: accentuate the positive in others. Accept that you are not God’s gift to men—you, too, have flaws. Don’t trust chemistry; it’s an unreliable predictor of long-term relationship success. (Ditto with first dates.) Let go of the fantasy of the singular soul mate. Some of the maxims that helped Gottlieb, of course, may not be so helpful for those with the opposite problem. Women who are not so much Samantha Jones as Bridget Jones are less likely to toss away perfectly good men than they are to rationalize bad ones. (If you by chance live in this other camp, part of the fun of reading Marry Him is anthropological: who are these brazen women who would dump a guy for refusing to say that, if she were to die, he’d never love another woman as much as her?) But everyone will likely find something useful in Marry Him—even if it’s just an opportunity to rail against society’s unwillingness to accept that you are, in fact, happily single, thank you very much.

The comment period has expired.

|

|