Arts of the Book Collection

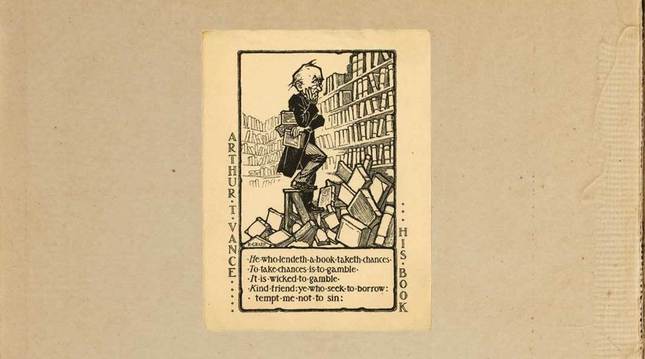

Arthur Vance's bookplate, donated to Yale by the Brooklyn Museum, heads off loans at the pass.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

Arthur Vance's bookplate, donated to Yale by the Brooklyn Museum, heads off loans at the pass.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

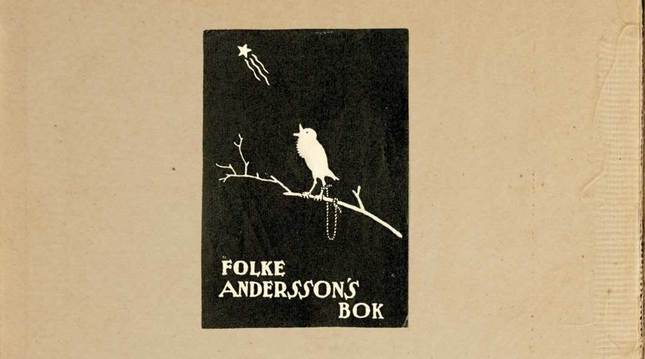

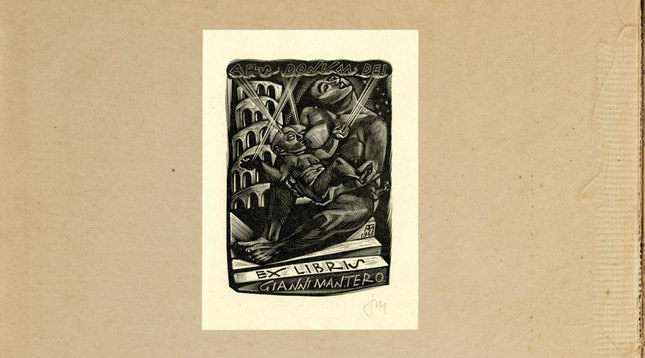

The bookplate above, drawn in a folk art style, is from the collection of Aleksander Kaelas, an Estonian bibliophile who collected plates from Eastern Europe and fled his home country in 1943. His wife donated 3,700 bookplates to Yale in 1964.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

The bookplate above, drawn in a folk art style, is from the collection of Aleksander Kaelas, an Estonian bibliophile who collected plates from Eastern Europe and fled his home country in 1943. His wife donated 3,700 bookplates to Yale in 1964.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

Early bookplates typically featured coats of arms—and it was a pretty safe bet that if you didn’t have a coat of arms, you couldn’t afford a book. Above: the bookplate of Catherine the Great of Russia is in French—customary for the Francophile empress.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

Early bookplates typically featured coats of arms—and it was a pretty safe bet that if you didn’t have a coat of arms, you couldn’t afford a book. Above: the bookplate of Catherine the Great of Russia is in French—customary for the Francophile empress.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

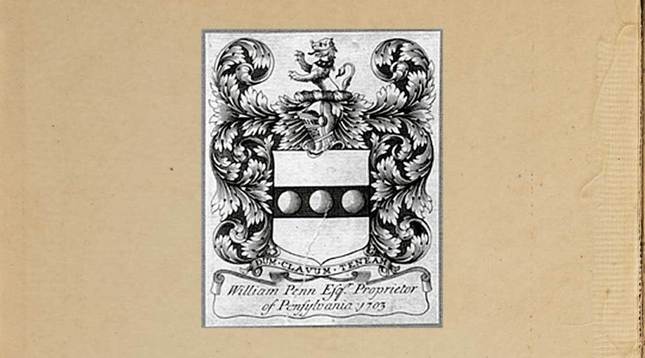

William Penn’s displays the Pennsylvania founder’s family coat of arms; its Latin motto means, “While I can hold the helm.”

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

William Penn’s displays the Pennsylvania founder’s family coat of arms; its Latin motto means, “While I can hold the helm.”

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

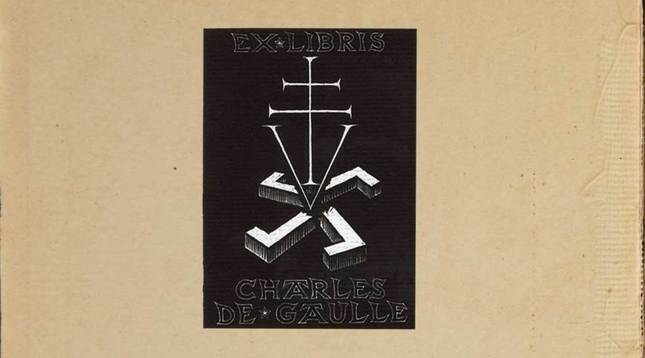

Charles de Gaulle’s bookplate features the Cross of Lorraine, symbol of the Free French, crushing the Nazi swastika with the V of victory.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

Charles de Gaulle’s bookplate features the Cross of Lorraine, symbol of the Free French, crushing the Nazi swastika with the V of victory.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

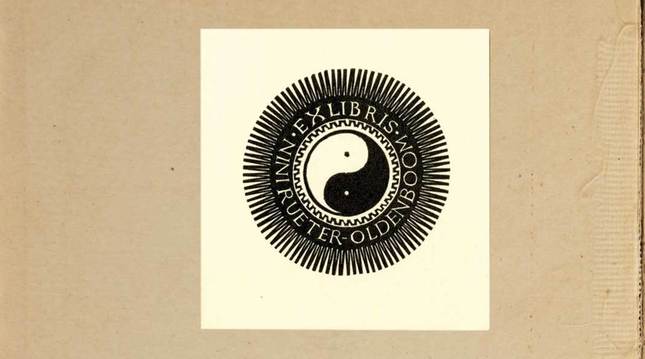

Nini Rueter Oldenboom’s bookplate is from Kaelas’s Baltic collection, despite its Asian iconography. It probably dates from the twentieth century.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

Nini Rueter Oldenboom’s bookplate is from Kaelas’s Baltic collection, despite its Asian iconography. It probably dates from the twentieth century.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

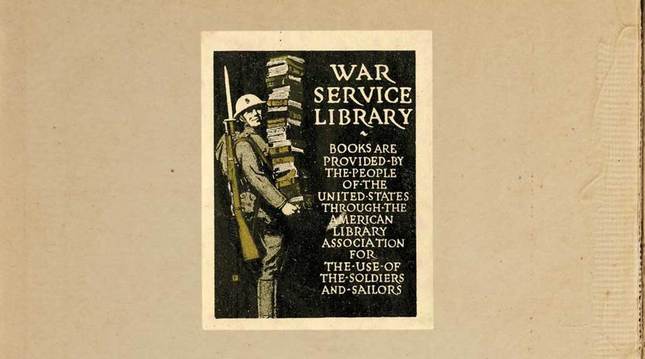

The War Service Library plate adorned many a book shipped overseas during World War I. This one ended up in a European collection.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

The War Service Library plate adorned many a book shipped overseas during World War I. This one ended up in a European collection.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

Arts of the Book Collection

Arts of the Book Collection

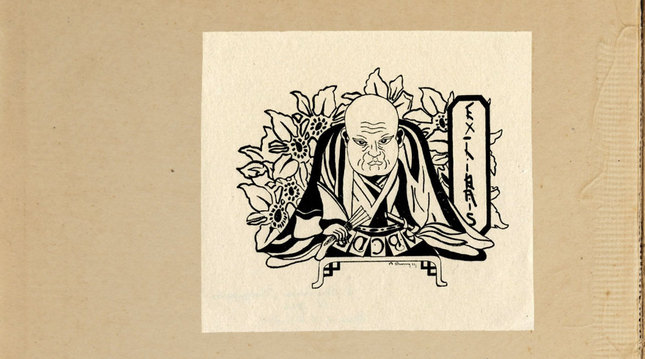

The Asian-influenced bookplate on the top right of this page is probably Western in origin; its lettering gives it away. It comes from the collection of Irene D. Andrews Pace, the largest contributor to the Yale bookplate collection. Her plates, divided into several smaller collections, number near 150,000—including 300 designs she commissioned for her personal library.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

The Asian-influenced bookplate on the top right of this page is probably Western in origin; its lettering gives it away. It comes from the collection of Irene D. Andrews Pace, the largest contributor to the Yale bookplate collection. Her plates, divided into several smaller collections, number near 150,000—including 300 designs she commissioned for her personal library.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

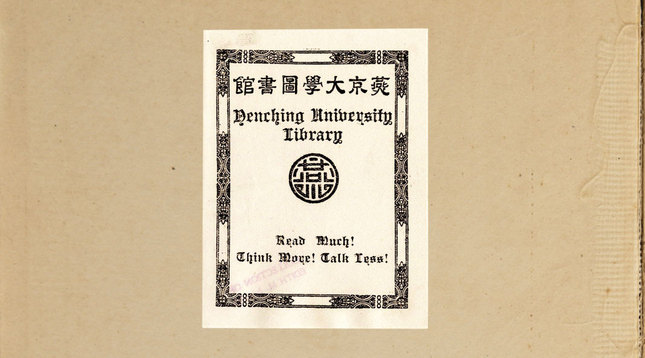

The bookplate from the Yenching University Library was one of several designs used by the American-run Beijing college in the early part of the twentieth century.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

The bookplate from the Yenching University Library was one of several designs used by the American-run Beijing college in the early part of the twentieth century.

View full image

Arts of the Book Collection

Arts of the Book Collection

Psychology of the bookplate

“This book belongs to me.” For over five centuries, that has been the message conveyed by every bookplate, whether printed and hand-tinted for Hildebrand Brandenburg in 1480 or mass-produced for Barnes & Noble or Amazon. (Yes, they sell bookplates.) Think of a bookplate as a wedding ring binding the reader to the book, and vice versa. The symbolism isn’t so far apart: ownership, possession, desire.

For centuries, books were precious. The first book printed with movable type, the Gutenberg Bible, was and is an object of veneration, and even three centuries later, books (as opposed to pamphlets) were artisanal productions. Samuel Johnson’s famous Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1755, initially sold at a rate so low it was reissued in affordable weekly installments. Books retained scarcity value for almost another century, until the era of the nineteenth-century “dime novel,” the throwaway precursor of today’s paperback.

Bookplates, often beautiful adornments to things of beauty, signify figurative possession as well. “Ex Libris Alex Beam,” meaning “From the Library of Alex Beam,” found on the inside covers of Anthony Powell’s series Dance to the Music of Time, would suggest not only that I owned the books, but that I had read them too. (Especially the tenth volume: Books Do Furnish a Room.) Here desire bleeds into possession; I do own them, and I wish I had read them all.

Lastly, a bookplate expresses the desire to be possessed, to inhabit the book itself. Look at the bookplate of Edith Treuhoff, sitting at her table, in front of her window, on a perfect day . . . inside her book! The book isn’t just an object, it is an imaginative territory, a world often represented in this collection by the stars, or by the moon. Who doesn’t want to live there? Along the banks of the Mississippi; in the whaling boat with the peg-legged madman; heck, I can lose myself driving the streets of Los Angeles in a beat-up limousine with Michael Connelly’s Lincoln Lawyer. Better there than here.

Where are we now? Books are changing from physical to virtual objects. Cushing Academy, a tiny prep school in central Massachusetts, achieved nano-fame by making electronic readers available in its library. Today’s curiosity is tomorrow’s Freshman Orientation Day on the Old Campus.

The 25-cent paperback took us halfway there; now we have fully arrived. The physical book does not exist, and has no value. The digital book has no front or back covers; there is no place to assert ownership, and there is nothing to own. The “digital delivery module” is a piece of molded plastic made in China, encasing a few memory chips. That is not the book, that’s the “reader.” Wait, I thought I was the reader. Oh, never mind.

Electronic bookplates? I don’t think so. “We have created a library for you on Amazon.com,” the manufacturer of the popular Kindle says, but I know they’re just kidding. If they had created a library for me, they would have included In Every Face I Meet, by Justin Cartwright, or Richard Holmes’s Dr. Johnson and Mr. Savage. Their library exists on a server farm, where real estate is cheap. My library is here, in this room where I am writing.

“This books belongs to . . . no one.” Welcome to the future, a less intimate and a less ornamented place.

loading

loading