loading

loading

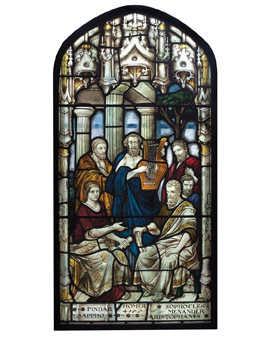

Light & VerityWindows’ fate is unclear Julie BrownOnly one of the 12 stained glass windows from the grand staircase of Linsly-Chittenden Hall has been found. View full imageThe mystery of Yale’s missing stained-glass windows, almost 40 years in the making, may be nearing an end—but not a solution. “We can’t account for them,” says Jock Reynolds, Henry J. Heinz II Director of the Yale University Art Gallery, which was charged with caring for the 12 panels that once graced the grand stairway in Linsly-Chittenden Hall. The confusion reflects Yale’s “severe deferred maintenance” in the 1970s and ’80s. The windows, made by Clayton & Bell of London and depicting literary figures, faced the Old Campus. Fearing for their safety before May Day 1970, when thousands of demonstrators were expected on campus to protest a Black Panther trial, the university had them removed and asked the gallery to add them to its collection. They were stored in Linsly-Chit’s basement, a low-security space shared with other departments. By 1987, an inventory found only a few cases of stained glass, much of it in pieces. Just one panel remained intact. What happened to the rest? “We don’t know what happened to them,” says Reynolds, who thinks they were likely lost, thrown out, or salvaged and sold by contractors. “This was a slip; no other way to describe it.” The Yale administrator who had ordered the windows’ storage had the wrong stained glass (as Richard Conniff ’73 wrote in “A Tale of Two Windows,” January/February 2010). He thought he was protecting Yale’s near-priceless Tiffany, but it stayed in place, unharmed, during May Day—while the Clayton & Bells, which have little or no value in the art market, weren’t as safe as he thought. Just before we went to press with the “Tale of Two Windows,” the gallery reported finding some promising crates of stained glass. But, Reynolds says, the contents turned out to be “other unknown, unattributed pieces of stained glass.” The confusion reflects more than just the chaotic times in which a Yale administrator hastily ordered the wrong windows removed and then, apparently, forgot to order their restoration. It also reflects the university-wide legacy of “severe deferred maintenance” in the 1970s and ’80s, Reynolds says—compounded, for the gallery, by inadequate storage and staffing and the difficulty of occasionally being asked to take in orphaned campus artifacts like the Clayton & Bells. When Reynolds arrived in 1998, the gallery had six off-site storage locations of varying quality and security. As Yale’s finances improved, and as the gallery staff was boosted by donors who have endowed 18 of its current 22 curatorial positions, Reynolds has had the scattered collections inventoried and cleared out. One space housed some 2,000 “architectural elements, plaster casts, and iron elements,” says gallery spokeswoman Ana Davis. The stored collections have been consolidated in a new state-of-the-art facility in Hamden. With the university’s massive infrastructure investments over the last two decades, “the whole nature of collection care has really been transformed,” the director says. In addition to the changes in staff and facilities, “there’s a lot of gifts we don’t accept.” The vast majority of the gallery’s collections were donated. But it will turn down a work for reasons of condition, quality, or redundancy with the existing holdings. “The admissions office takes only 7 percent of applicants,” he says. “We take more than 7 percent. But we can’t take everything, because we can’t take care of everything. It’s like having a kid: making love and conception are great, but it’s yours for life.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|