loading

loading

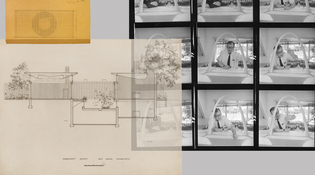

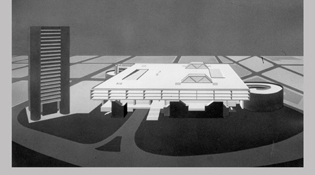

featuresThe architect at workArt history isn’t just the finished product. You also need to see the rough drafts.  Manuscripts & ArchivesA contact sheet (above right) with portraits of Eero Saarinen ’34BFA and a model of his St. Louis arch is part of the extensive Saarinen collection in the Yale library's architectural archives. At left is a cross-section of the Manuscript senior society building (1962) designed by King-Lui Wu, and a sketch of the building's facade. View full image

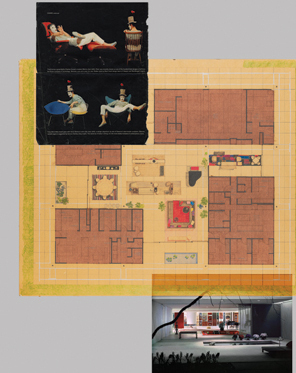

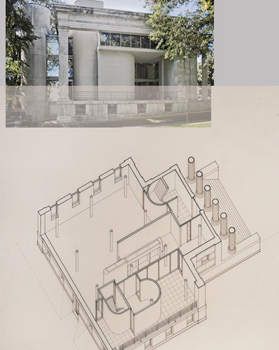

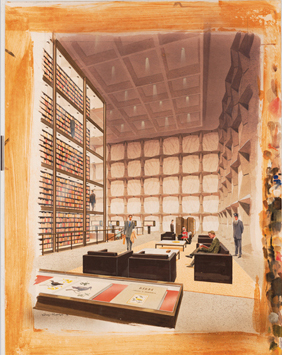

Architect Paul Rudolph taught at Yale, and he made his name at Yale, and it was at Yale that he created his masterwork—the Art & Architecture building, now called Paul Rudolph Hall. He designed the building here, running through six different schemes that got ever more complex, and he himself oversaw its construction—acting essentially as his own client, fretting over details and redesigning even as the building was going up. When it was finished in November 1963, two thousand people, including the crème de la crème of American architecture, came to the dedication, and the New York Times reported that “in a field torn by polemics, architects at opposite esthetic poles are united in praise” of Rudolph’s building. But if you want to see how that building came to be—if you want to see the early sketches, the many different iterations, the correspondence with Yale officials and subcontractors—you have to go to Washington, DC: Rudolph left his papers to the Library of Congress when he died in 1997. “Rudolph’s papers went to the Library of Congress because as far as I know, nobody here thought to ask him,” says Robert A. M. Stern ’65MArch, dean of the School of Architecture. “They really should be here.” Since shortly after becoming dean in 1998, Stern has been on a campaign to make sure that if an architect’s papers end up somewhere else, it won’t be because Yale didn’t ask. Other institutions—Columbia, Penn, the Getty Center, and the Canadian Centre for Architecture—are well known for deep and broad archives in architecture. But despite the prominence of Yale’s architecture school—it consistently ranks in the top five American schools—the university had never made a point of collecting architects’ papers until 2000. That was when Stern and Richard Szary, then director of Yale’s Manuscripts and Archives collection, outlined a plan to solicit and collect those papers, with a special focus on architects and firms with faculty or alumni ties to Yale. The first major gift was a coup: the papers of Eero Saarinen ’34BFA, a famed midcentury architect as intimately associated with Yale as Rudolph was. The papers were the gift of Kevin Roche, the Connecticut-based architect who designed the Knights of Columbus building in New Haven and the Ford Foundation headquarters in New York. Roche was working for Saarinen when Saarinen died suddenly in 1961; he and partner John Dinkeloo took over the practice and inherited the Saarinen office’s files. When he gave them to Yale in 2003, the university got a grant from the Getty Foundation to process the papers and develop a book and exhibition based on the material. (See “Eero Saarinen’s Turn,” September/October 2006.) The gift of the Saarinen papers and the Getty grant allowed Yale to hire Laura Tatum, an architectural archivist. Yale also attracted other high-profile donations, including the papers of Cesar Pelli, the former Yale dean who designed the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur; Cooper Robertson & Partners, the firm that created Battery Park City in New York (and Yale’s most recent master plan); and Charles Gwathmey ’62MArch, who designed additions to the Guggenheim Museum in New York and to Paul Rudolph Hall at Yale. Kevin Roche has also given Yale his own firm’s papers. Just as literary scholars mine the papers and manuscripts of authors for hints into their creative processes and influences, scholars of architecture pore over the drawings, correspondence, and office records of architects and firms to see how important buildings were designed and built. And Stern says the material is of historical value in other fields. “In the university culture, archives like this are not just for art appreciation. They also open a window onto corporate and institutional life.” Saarinen, for example, designed major edifices for CBS, TWA, and AT&T. Tatum, who got her start as an undergraduate working in Columbia’s Avery Architectural Library, says that when working with potential donor firms, she’s looking for “materials that tell the story of the design: early design drawings, architectural and structural drawings, early schematic drawings, different versions of a project presented to a client. And correspondence. Correspondence is the most valuable thing. That really tells the story of the project. Even things you wouldn’t think of such as telephone notes. Sometimes when you’re going through the telephone notes you can tell that a project is going south well before the final letter comes in saying, ‘your services are no longer required.’” Of course, architects don’t work just on paper anymore. Archivists are still trying to figure out how to preserve records that they call “born digital”: drawings and correspondence that were created on computers and perhaps never printed. How to keep these records usable even as their native formats and software become obsolete is “the $64,000 question not just for us but in the archives profession in general,” says Tatum. Yale and three other schools have a Mellon Foundation grant to develop what Tatum calls a “multi-institutional approach” to digital records preservation “so that each institution doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel every time.” Yale now has around 50 collections in its architectural archives, a lot more than ten years ago, but, as Stern says, it’s “still playing massive catch-up” with more established institutions. So far, Yale has had to depend on the generosity—and sometimes the loyalty to Alma Mater—of its architect donors: the archive has no budget to buy papers, although some architects prefer to sell theirs. (Four years ago, the New York Times reported that Frank Gehry was said to be marketing his for a “multimillion dollar” price.) Stern, for his part, has already started donating the archives of his own very busy New York firm. And the Stern papers are unusually comprehensive—they include a cache of architectural drawings Stern made when he was still in grade school. “I probably shouldn’t have” included them, Stern says. “Way too embarrassing.”  Manuscripts & ArchivesThe Saarinen papers include detailed documentation of the furniture the architect designed for the manufacturer Knoll in the 1950s, from colored pencil sketches (upper right) to patent drawings (below left). At lower right, a photo from the collection shows Saarinen associates Cesar Pelli—who would later be dean of the Yale School of Architecture—and John Buenz (foreground) working on a mockup of the concrete and stone walls for Ezra Stiles and Morse colleges at Yale. View full image Model photo: Ezra stoller/ESTO. Others: Manuscripts & ArchivesA plan and model photo (lower right) show the decorating scheme by Alexander Girard for a house in Columbus, Indiana, designed for J. Irwin Miller ’31. At top is a magazine advertisement featuring Marcel Marceau for Saarinen-designed Knoll furniture. View full image Above: Brian Rose. Below: Manuscripts & ArchivesThe papers of Charles Gwathmey ’62MArch—recently received at the Yale archives—include this diagram of Gwathmey's 1971 renovation of Princeton's Whig Hall (completed, at top). View full image Manuscripts & ArchivesEven before Yale began seeking out architects' papers, the university's archives kept drawings and photographs from Yale's own construction projects. Renderings like this one of Gordon Bunshaft's Beinecke Library (1964) might have been used in presentations to the public or to potential donors. View full image Manuscripts & ArchivesA drawing from the Kevin Roche papers explains the relationship of the New Haven Coliseum (a Roche design completed in 1972 and demolished in 2007) to the Knights of Columbus building, also a Roche design. View full image

The comment period has expired.

|

|