loading

loading

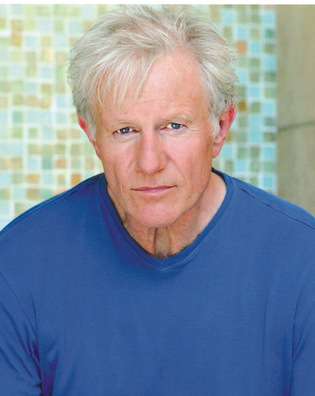

Where They Are NowMake room for Daddy Courtesy Raymond BarryRaymond J. Barry ’65DRA spent years in theater in New York, but he's best known these days for playing fathers in film and TV. View full image

You could say that Raymond J. Barry ’65DRA is a professional father. On film and in television, he’s parented A-list stars like Tom Cruise (Born on the Fourth of July), Ashton Kutcher (Just Married), and Vince Vaughn (Return to Paradise), and he’s had a son murdered by Sean Penn (Dead Man Walking). He’s even been John Terry’s father on Lost, which kind of makes him the father of God. Despite all this experience, Barry (who attended the Yale School of Drama but did not graduate) lives just outside the spotlight. But his latest role—as Timothy Olyphant’s duplicitous dad on the TV western Justified—proves that an actor doesn’t need fame to do interesting work. In anticipation of the second season, airing now on the cable channel FX, Barry recently spoke about his lengthy career. Y: On Justified, you play Arlo Givens, the unstable father of a local lawman. He’s attractive and repulsive at the same time. B: It’s a good role. He’s charming on the outside, but he gets violent and goes off the beam. And he’s also a drug dealer. Y: What’s it like working on that show? B: The people are great. On that set, you show up, and instead of just shooting it, they talk about the scene. And sometimes they tear it apart and make it better. The idea of sitting down and talking about it and working with the writer on the set—it’s unheard of. But they want a good show, and they’re willing to do something about it. Y: You’ve been working steadily for almost 50 years, but you’ve never become a superstar. Have you ever wished you were more famous? B: If I’m really being honest, I would’ve loved to win all kinds of awards in my forties and fifties. And even today, last year, I was given a lifetime achievement award by the Gasparilla International Film Festival [in Florida]. That was a lot of fun. But now, I’m not trying to win Oscars and trophies. I can’t worry about that, because what am I going to win? The “rising star” award? Y: Are there any roles you get recognized for? Maybe the mysterious senator on The X-Files? B: I did a film, Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story [playing the father of a Johnny Cash–inspired country singer]. That was wonderful because it was a comedy, and I’m very seldom hired to be funny. People come up to me and say an emblematic line from the movie—“The wrong kid died!”—which is what my character says about his son. Y: And of course, people who knew you at the beginning of your career might be surprised to see you on screen at all. In the 1960s and ’70s, you worked with some of America’s most influential experimental theater troupes, including the Living Theatre and Joseph Chaikin’s famously political Open Theater. What was that like? B: It was a magical experience, and it was happening at a fervent time. Integration was happening. Vietnam was a huge conflict, and Joseph Chaikin was a Marxist, whatever that means. You could have accused us all of being communist, with what was flying out of our mouths. And we were getting the kind of notoriety from newspapers and magazines that gave us a hint that we were making an impact. Y: How did working with avant-garde artists compare with your undergraduate theater training at Brown and your graduate work at Yale School of Drama? B: Well, [with the Open Theater] we did 200 performances a year, which in terms of honing your craft is a great thing. And theater like the Living Theatre and the Open Theater didn’t exist in the late ’50s and the early ’60s, or it hadn’t yet come into its own. I had no idea there was a type of theater that put images before plot, that was episodic and emotional and all of that. In the academic settings, I worked from scripts, and everything was very linear and clear. The focus was on things that made me feel self-conscious. I spent my time questioning how I talked instead of embracing who I was. When I realized that who I was had value, that’s when I started to relax as an actor. That took years. I had to undo a lot of what I learned at Brown and at Yale. Y: You didn’t move to film and television until the ’80s. Why the long wait? B: At the time, it was very politically correct to condescend to Hollywood, and you could make a living in the theater anyway. You could work Friday, Saturday, and Sunday and make your rent for the week. My first rent was $49 a month, and it never went beyond $150 after living in the same SoHo loft for 17 years. Eventually, though, when I was in my forties, my rent got jacked to $650 a month and my daughter was approaching college age. I said, “I have to be in movies to make more money.” I also began to notice that there were actors on the Lower East Side who never got out. I did many plays at La Mama and the Public [Theater], but it began to feel provincial after a while. I decided I needed to do something broader, and it was a shot in the arm to start doing film. Y: How have you changed as an actor since you first came to Hollywood? B: The joy that I’m experiencing in my life allows me to have a great time when I work. In my twenties and thirties and forties, I would bring a condition of anxiety. “Am I going to be good? Am I good?” Today, I don’t give a fuck, and I can’t tell you how freeing that has been for me. Y: Does that mean you don’t like your earlier performances? B: I don’t want to give that impression. I love the scene I did with Tom Cruise in Born on the Fourth of July. I don’t think I could do better. But the sense of tension I brought was unbearable. I knew I’d done a day’s work, if you know what I mean. Now I care in the sense that I will do the job, but I don’t care in terms of ego. Y: It almost sounds counterintuitive, improving your work by relaxing. B: It makes the work better. I was an athlete in college, and the more effort I put into being an athlete, the better. But that’s not true of acting. To be general, acting is about learning just to be.

The comment period has expired.

|

|