loading

loading

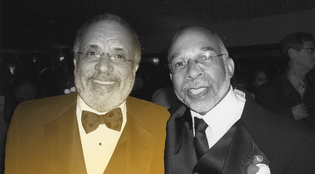

Before their time Courtesy Monica MurphyClyde Murphy posed with the author (above, at right in photo) at the author's son's wedding in 2005. View full imageWeeks later, on the afternoon of August 17, I was finishing a jog around Prospect Park and stopped to watch as medical technicians carried off a man who had been struck by a bicyclist. It was at that moment that my son Damani called to tell me that Clyde had just passed away, suddenly, in Chicago. My mind and mouth fell stupidly silent. A cold nothingness overcame me, an emptiness that was the converse of my feelings about Clyde. I admired him so. For three decades I had watched as Clyde, a Columbia Law grad, battled racial discrimination in the American workplace. He was for 19 years a top counsel with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, arguing before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1984. In 1995, he became executive director of the Chicago Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. Last year, three months before his death, he savored the sweet victory of a Supreme Court decision in his favor, upholding a complaint he had brought alleging discrimination against blacks who had taken the Chicago firefighter entrance exam. Perhaps most importantly, in my eyes, Clyde was a model of black fatherhood, an institution that has been a social battlefield over the past two generations. There have been horrific defeats for black Americans on that battlefield due to an absence of valor and commitment, but Clyde was among the outstanding generals. Several years ago, with a sense of urgency that he conveyed to me in a telephone conversation, he traveled from Chicago to North Carolina to spend time reasoning and arguing with his son Jamal, who Clyde felt was not stepping up the ladder of achievement with enough energy. Call it being pushy on Clyde's part, or meddling, if you will, but Jamal soon afterward decided to go to law school. He is a lawyer now. Just before Clyde's death, Jamal had picked his dad to be best man at his approaching wedding. I spoke at Clyde's funeral, recalling his undergraduate time as the Platter Playin' Poppa of WYBC. I vowed to better understand and embrace the past that Clyde and I shared. Weeks after the funeral, I did some counting and came up with 84 members of the Class of '70 who were deceased, nine of them blacks who entered with us in 1966. Thus, while we African Americans were 3 percent of the Class of '70, we were more than 10 percent of the deaths. Put another way, we have been more than three times more likely to die than the average class member. Demographers tell me not to extrapolate too far with these numbers, which are by no means a valid sampling. But for those of us who have been thinking about this for years, the numbers have profound meaning. Denis E. Kellman '70, an attorney, lost his two best friends, Carl Palmer '70 and Ron Norwood, in 2005 and this past February, respectively. "I feel like the last man standing," Kellman says.

|

|