loading

loading

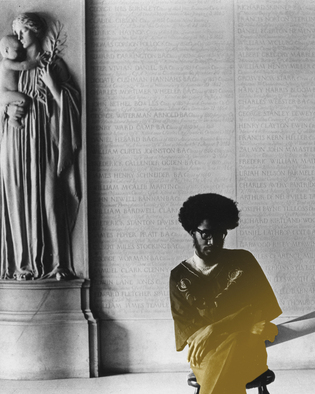

Before their time Manuscripts & ArchivesArmstead Robinson ’68 cofounded the Black Student Alliance at Yale, whose first president was Glenn DeChabert ’70 (pictured next page). The author says he remembers "an intensity about them that put them in the Type-A category, driven to succeed, full of energetic questioning." Robinson died in 1995. View full imageThat black males overall die before others in America is well established. According to the latest National Vital Statistics report, life expectancy is 80.6 years for women in America overall and 75.7 for men. For white women, it's 80.9; for black women, 77.4. For white men, 76.2. For black men, 70.9. Much of that difference can be ascribed to poverty, violent crime, and inequitable access to health care, and might be expected to narrow for black men of higher socioeconomic status. So the question is this: are the black men who went to Yale and similar institutions in the throes of the blooming civil rights era of the '60s—and who represented the first significant presence of African Americans on Ivy League campuses—now experiencing inequality in death, as their forebears did in life? Many scientists, it pains me to report, believe the answer is yes. Sociologist David R. Williams has done research showing that racial disparities in death rates pertain at "every level of income." In a 2002 paper, Williams went on to say something as surprising as it is ominous: "This pattern has been observed across multiple health outcomes, and for some indicators of health … the racial gap becomes larger as [the socioeconomic status] increases." Counterintuitive as that may sound, it makes a certain grim sense to Craig Foster '69. Foster postulates that for many blacks, an Ivy education opened doors of aspiration and ambition, but not necessarily corresponding doors of opportunity. For many, he says, the effort to win the success they desired caused strain, fatigue, and dejection. "Sometimes I wonder whether some of the brothers see death as the honorable way out," says Foster, now a broadcast agent living in his native New York. "In dying of stress, you leave open the perception that you fought the good fight, that you took your sword and resisted the onslaught of your enemy before you finally went down yourself." A number of experts would agree with Foster, it seems. Some of them back up sociologist Williams's findings, saying that not only do higher-income black males fare worse than their white counterparts, but they also fare worse—in terms of morbidity and certain illnesses—than lower-income, less highly educated blacks. One reason for this, researchers believe, is a phenomenon known as "John Henryism," a determination among these men to succeed even at the cost of their health. Duke psychiatrist Christopher L. Edwards explained the idea in reporting on a 2006 study: People who are so intensely success-oriented and goal-directed, even beyond their resources such as income, education, or family support, might seem to succeed at first. But, long term they are likely to fail because their lack of resources will catch up to them. Add to that the African American situation, which, for many, includes an expectation that failure is inevitable, and you find yourself in a most destructive situation. They end up compromising their health, with higher rates of cardiovascular disease and death. John Henryism was first identified by a public health researcher in a 1983 study on hypertension in black men. It takes its name from the black folk hero who, big in size and grand in strength, banged steel spikes into place during the nineteenth-century railroad boom. To save his job and those of other black "steel drivers," John Henry offered to show that he drive spikes better than the steam-powered hammers the bosses were introducing to save money. Henry labored valiantly, but he died in the effort. "Before I let this steam drill beat me down," goes the song, "I'll die with my hammer in my hand." Keith C. Ferdinand MD, chief science officer for the Association of Black Cardiologists, attended Cornell in the late 1960s. He says he is very aware of the experiences that have led African American men, including very educated ones, to relatively high mortality rates. He says hypertension in black men may be related to "intensive stress when it comes to achieving in an environment where they're underappreciated or working against barriers." Charles Finch, the doctor among our group of black Yale men, has been saying this for a long time—that the prime suspect in the early deaths we have been experiencing is stress. The problem, however, is that there is no sure way to identify and measure stress the way doctors measure, say, hypertension, and no medications or even behaviors to combat it. "Stress may play a part, but we don't list it as a risk factor because it's so hard to put your finger on what stress is," Ferdinand told me.

|

|