loading

loading

Old YaleA mover and shaker of the Gilded AgeTimothy Dwight demolished a fence and built a university. Judith Ann Schiff is chief research archivist at the Yale University Library.

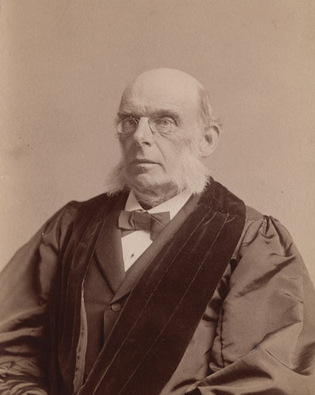

Manuscripts & ArchivesTimothy Dwight studied and worked at Yale almost all his life, from his undergraduate years through his 13 years as president of Yale. View full image

The second Yale president who was named Timothy Dwight was also the last minister to serve in the office (1886–99). Today this is the distinction for which Timothy Dwight the Younger—usually overshadowed by his better-known namesake, grandfather, and predecessor—is often remembered. But the younger Dwight (1828–1916) was one of Yale’s greatest presidents. He charted and carried out a plan that transformed Yale from a languishing college to a preeminent university in 13 short years. One of a privileged few who did not have to support themselves after graduating from college, Dwight, Class of 1849, spent two years as a graduate student at Yale at a time when there was no prescribed course of graduate study. He then entered the Divinity School, at the same time taking on what one of his memorialists, Professor Benjamin W. Bacon, Class of 1847, would later call the “laborious office of tutor.” In that post, said Bacon, Dwight did more “than any other man … to initiate the change of relations between the faculty and students from those of armed neutrality toward the more modern attitude of friendly cooperation.” At the time, a tutor not only gave basic instruction in all undergraduate courses, but also served as a dormitory dean and campus policeman. Young Dwight knew well the hazards of the position: in 1843 his older brother John Dwight ’40, then a tutor, had been stabbed three times by a drunken student and died of infection. But Timothy Dwight befriended the students, who called him “Tutor Tim.” Once, Bacon remembered, Dwight was awakened by some student pranksters. He dutifully chased after them, but when he found himself about to catch up, called out, “Gentlemen, if you do not run a little faster I shall be obliged to overtake you.” In 1855 Dwight went abroad to travel and study. He was appointed assistant professor of sacred literature in 1858, and in the first year of the Civil War was ordained and began 25 years as a Divinity School professor. His administrative and fund-raising talents became clear as he worked for construction of a new High Victorian complex for the school, built on the site where Calhoun College now stands. From 1866 to 1874 Dwight was editor of the New Englander, a literary periodical that has evolved into today’s Yale Review. His outstanding contribution was the series “Yale College; Some Thoughts as to Its Future,” published during 1870–71. In this series he laid out a clear plan for Yale to upgrade itself from a “college surrounded by outside schools” into a genuine university. The first step was to appoint a president both qualified and enabled to be more than “the senior professor of the Academic Department.” Fifteen years later, Dwight himself became that president and set about implementing his plan. In 1886 the graduate school needed a building and new professors. The two undergraduate departments—the liberal arts college and the Sheffield Scientific School—had to stop competing and cooperate. And Yale needed money. As Bacon put it, Yale, after losing its mid-century status as the largest American college, had been eking out a hand-to-mouth existence, “looking backward and choosing as its highest ambition to avoid the mistakes of Harvard.” Dwight set an example for the alumni by giving back his Yale salary and donating over $100,000 of his own assets to the university. While he searched for the right person to appoint as treasurer (it would be William Whitman Farnam ’66), he served as acting treasurer for two years without pay. Dwight faced his greatest administrative challenge in 1888, when he ordered the destruction of the Old Yale Fence—a wooden rail fence, running along the south and east sides of what is now the Old Campus, where undergraduates traditionally congregated. A donor had offered funds for a new building on that corner, but many alumni were outraged at the prospect. Dwight persuaded the Corporation, Yale’s governing board, to accept the gift. Years later, his New York Times obituary would quote in full his pronouncement on the decision (and on the folly of refusing a windfall): “Gentlemen, the Corporation did not consider it wise to endanger a gift of some $200,000 for the sake of a little sentiment. You know it is an old saying that lightning does not strike twice in the same place. I suppose that the best reason that has ever been given for this phenomenon of nature is that given by the small boy, ‘because it does not have to.’ Good day, gentlemen.” When Dwight stepped down in 1899, the Corporation saluted his achievements, including doubling the endowment, erecting numerous new buildings, increasing annual income by 150 percent, and enlarging the faculty by 125 percent and the number of students by 135 percent. Also notable were inaugurating the degree of Bachelor of Fine Arts in 1891, admitting women to the graduate school in 1892, and opening the School of Music in 1894. And Dwight had had Yale’s name changed, from Yale College to Yale University—a statement of its new status. Timothy Dwight had another legacy: he was probably the only Yale president until Whit Griswold ’29 to be known for his sense of humor. At his memorial service he was described as witty, droll, sunny, genial, and optimistic—even “the life of the party.” He had good reason for cheer. Dwight had revealed his personal secret of happiness in an 1887 speech: “The happiest person is the person who thinks the most interesting thoughts.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|