loading

loading

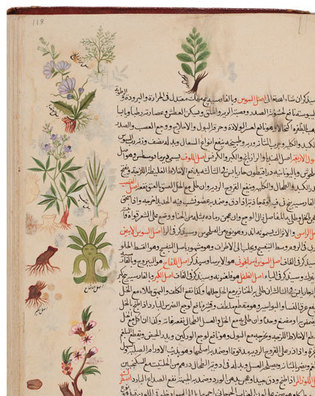

Arts & CultureAspirin, bed rest, and asl al-susObject lesson Melissa Grafe is the John R. Bumstead Librarian for Medical History at Yale’s Cushing/Whitney Medical Library. Abdul Ahad Hannawi is the Near East Catalog Librarian of Sterling Memorial Library.  Cushing/Whitney Medical LibraryThis Arabic manuscript, known as the Treasure of Medicine, gives advice on the medical uses of licorice root, sugar cane, mandrake root, and many other substances. View full imageThis beautifully illustrated manuscript is a 1612 copy of the Kitab Kanz al-hikmah*, or Treasure of Medicine, an influential twelfth-century Arabic text on medicine and pharmacology. In this book, the physician Abu Said ibn Ibrahim al-Maghribi compiled knowledge that had been developed in the Islamic world during the three previous centuries—the work of illustrious scholars who flourished in the Arab world during that period, even as Europe was experiencing what some have called its Dark Ages. Among the authorities Abu Said drew on were Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi (809?–873), who translated the medical texts of Galen and other Greek thinkers; al-Razi (865?–925), considered the greatest Islamic physician of his era; and Avicenna (980–1037), author of a major medical textbook. Some of the medical works produced in the Islamic empire by these and other scholars, and works they translated from ancient Greek texts, were later translated from Arabic into Latin and Hebrew and were used as standard medical reference texts in Europe up until the sixteenth century. Most of the plants and animals portrayed in the Treasure of Medicine are easily recognized today. (The book’s full name is the Kitab Kanz al-hukama wa-matlab al-atbba wa-al-ulama: Book of Treasure of the Learned and the Demand of Physicians and Scholars.) On this page, we can identify licorice root (asl al-sus) as the plant shown at the top of the page, centered over the text. The author tells us that it “is useful for roughness of the chest, lungs, and throat, and it calms thirst.… It is useful for dystocia; burning of urine and urethra; pain in the nerves, chest, liver, and kidneys; and bladder infection. Its jam and cooking are useful for different kinds of coughing.” Sugar cane—asl al-qasab, or “root of reed”—is also pictured here (to the right of the tall plant with small purple flowers). It is identifiable by its thick, jointed stem and narrow, pointed leaves and was useful, we learn, as a pain reliever. Also on this page and just below the drawing of sugar cane is an anthropomorphic picture of mandrake root, which was usually drawn in the shape of a man and supposedly screamed when pulled out of the ground—a medieval belief widely known today because of the Harry Potter books. Elsewhere in the book are pictures of an elephant and a rhinoceros. (Holding the rhino’s horn “benefits colic.… Steam infused with shreds of the horn benefits hemorrhoids.”) This copy of the Kitab Kanz al-hikmah was owned by the physician Abd Allah ibn Abd al-Muttalib al-Khalidi al-Khurasani, who had it reproduced for his collection. (It has now been reproduced digitally through a grant from the Arcadia Fund, and will soon be online.) We do not know the artist or scribe, only that the manuscript was finished on 23 Ramadan, 1021 H—or November 17, 1612. It came to Yale’s Medical Historical Library as part of the extensive book collection of the pioneering neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing, Class of 1891.

* Diacritics have been omitted from the transliterations of Arabic in this article.

The comment period has expired.

|

|