loading

loading

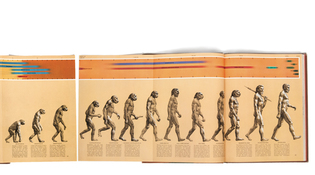

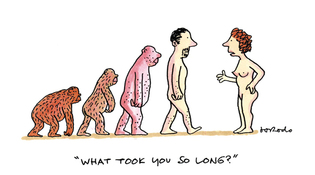

featuresIconic. Almost by accident.Nearly 50 years ago, a Yale graduate created an image that became part of America’s visual vocabulary. Richard Conniff ’73 is the author of The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth. Geoffrey Giller ’14MESc writes for Scientific American and Audubon.  Rudolph Zallinger ’42BFA, ’71MFA, from Early Man (Time-Life Books, 1965)When the foldout page is closed, this image in the 1965 Time-Life book Early Man, drawn by Rudolph Zallinger ’42BFA, ’71MFA, shows only six steps in human evolution. The image has been endlessly parodied. View full image The complete March of Progress covers four and a half pages, from Pliopithecus, “one of the earliest proto-apes,” to “Modern Man”—who, the text explains, is physically similar to his predecessor, Cro-Magnon man, but set apart by culture: “permanent settlements—and civilizations.”

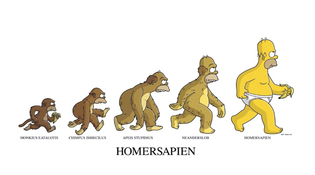

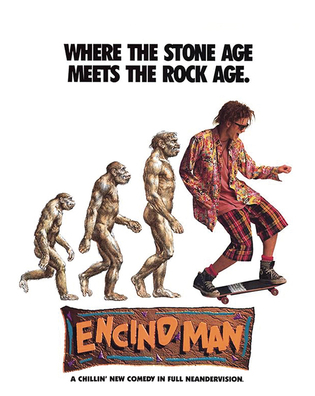

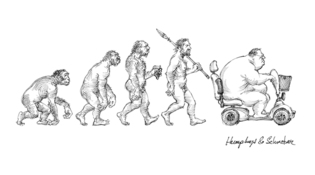

When the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale unveiled one of the largest murals in the world, shortly after World War II, the New York Times splashed the image across six columns of type. The 110-foot-long, 16-foot-tall painting, called The Age of Reptiles, depicted roughly 300 million years of dinosaur evolution, from the Devonian through the Cretaceous periods, and, according to paleontologist Karl Waage, later the museum’s director, it “put the museum on the map.”  Courtesy PeterphotographicMarch of Progress has been used for a huge variety of marketing and satirical purposes. Above, an apocalyptic version—street art from a 208 London festival. View full image Wilbur/Dawbarn; CartoonstockA cartoon targeting Cyber Man. View full image FoxProgress per Simpsons creator Matt Groening, with "Neanderslob" evolving into "Homersapien." View full image Phil Roberts/DisneyA poster for Encino Man, a 1992 movie. View full image Tone Cartoons, Ltd.An image that only Doctor Who fans will understand; the Daleks are an extraterrestrial race of cyborg villains. View full image Amazon.com"Robot Evolution," for sale on Amazon (and familiar to fans of The Big Bang Theory.) View full image Courtesy Head Ov MetalOne vision of a wheeled future: street art from Austin, Texas. View full image Humphreys and Schmelzer/CartoonstockA different vision of a wheeled future. View full image Jorodo/CartoonstockA woman shows up in the human family tree. View full imageIt also made a name for Rudolph Zallinger ’42BFA, ’71MFA, a young Russian-born graduate of the Yale School of Fine Arts, who had spent more than four years on the mural. His work won the 1949 Pulitzer Fellowship in Art, and it caught the eye of editors at Time-Life; in 1953 Life magazine published a foldout image of the entire mural. (Hence Zallinger’s image of Tyrannosaurus became an unintended inspiration for the main character in a 1954 film from Japan called Godzilla.) Zallinger continued to work on assignments for Life and Time-Life Books after that. In the course of one such assignment, he made cartoon history, almost by accident, with a visual trope that’s instantly recognizable and yet almost never attributed to him. It started with an illustration he produced for the 1965 Time-Life book Early Man. In a section headlined “The Road to Homo Sapiens,” Zallinger depicted a line of proto-apes, apes, and hominids rising from a crouch to a hunch to the tall, upright, almost erudite modern man. The full fold-out spread showed 15 individuals, starting with Pliopithecus and ending with Homo sapiens. But when folded in, a more simplified version appeared, with just six individuals. It became known as March of Progress, from a line in the text, and it went on to become one of the most famous images in the history of scientific illustration, almost as familiar as Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. In fact, similar drawings had appeared as far back as T. H. Huxley’s 1863 book Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature. But after Zallinger, it became a meme. In the half century since Progress first appeared, versions of this drawing have turned up, among other improbable places, on the cover of a Doors album, as the emblem of the Leakey Foundation, and as an ad for Guinness—the final stage in primate evolution evidently involving an Imperial pint. Among more-recent parodies, one cartoon depicted modern man as a bloated fast food customer who evolves into an actual pig. Another, drawn by Simpsons creator Matt Groening, depicted “Neanderslob” evolving into “Homersapien.” But serving the whim of editors at Time-Life didn’t work out so well for science. Evolution isn’t necessarily about progress, as that Homer Simpson example might suggest. In his 1989 book Wonderful Life, paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould fumed that March of Progress had become “the canonical representation of evolution—the one picture immediately grasped and viscerally understood by all.” It was a “false iconography,” he wrote. “Life is a copiously branching bush, continually pruned by the grim reaper of extinction, not a ladder of predictable progress.” According to one of Zallinger’s daughters, Lisa David, her father had also objected to the linear layout. He had drawn each figure separately, and he worried that presenting them as a continuous series misrepresented “from a scientific point of view, how this whole evolution occurred.” In his critique, Gould added that his own books were “dedicated to debunking this picture of evolution.” But the iconography of March of Progress had by then become too powerful and pervasive to dislodge. It had already turned up on the foreign-edition covers of a book by, yes, Stephen Jay Gould.

|

|

1 comment

-

Johannah Rodgers, 2:56pm November 26 2014 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.Thanks for this article! Very interesting.