loading

loading

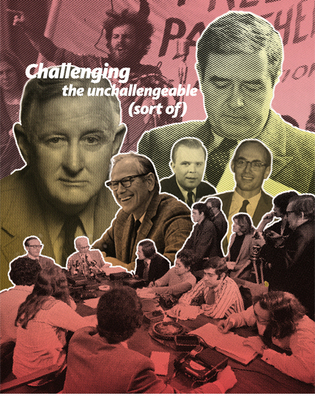

featuresChallenging the unchallengeable (sort of)Forty years ago, a committee led by C. Vann Woodward created a lofty statement about free expression. But there was some pragmatic politics behind its creation. Nathaniel Zelinsky ’13 is a Paul Mellon Fellow at Clare College Cambridge. This article was adapted from his senior essay at Yale.  Photo illustration: Mark Zurolo ’01MFA. Photos: Manuscripts and Archives.Amid provocations like the 1970 May Day protest (top, with Jerry Rubin), President Kingman Brewster Jr. ’41 (top right) took criticism over the disruption of speech on campus. History professor C. Vann Woodward (center, far left) chaired the committee that wrote Yale’s policy on free expression. Political science professor Robert Dahl ’40PhD (center,

second from left) wrote the report’s oft-quoted opening section. Brewster aide Henry “Sam” Chauncey Jr. ’57 (center, second from right) and provost Charles Taylor ’50,

’55PhD (center, far right) struggled with free-speech controversies.

So declares the Report of the Committee on Free Expression at Yale, commonly called the Woodward Report after the committee’s chairman, historian C. Vann Woodward. Celebrating its 40th anniversary this January, the Woodward Report has defined the university’s policy on the open exchange of ideas since its publication in 1975. This August, responding to controversial graduation guests being disinvited and speakers silenced at schools around the country, President Peter Salovey ’86PhD made the report and its ideas the centerpiece of his welcome address to freshmen. (See “Free Speech at Yale,” November/December.) Because of its principles and wisdom, he told students, the document continues to guide Yale on the importance of open discourse. Yet, while the Woodward Report is, as Salovey indicated, a timeless statement of Yale’s commitment to unfettered dialogue, it is also the product of a particular moment in time and of a singular group of Yale faculty and alumni. Not just the lofty, philosophical treatise we know it as today, the report was a carefully calibrated political tool of then-president Kingman Brewster Jr. ’41, which he used to rehabilitate his and the university’s tarnished image after several years of mistakes regarding free speech. The direct impetus for Woodward’s committee came on the night of April 15, 1974, in Strathcona Hall. Nobel Prize–winning physicist and inventor William Shockley was to debate William Rusher, publisher of the conservative magazine National Review, about Shockley’s belief in the genetic inferiority of African Americans. But the debate never happened. Objecting to the scientist’s abhorrent views, student protesters disrupted the debate, clapping, stomping, and chanting in their seats to drown out the speakers. Because of Shockley’s national infamy, the affair received attention and criticism around the country. For Brewster, the Shockley predicament was unfortunately familiar. The beginning of his presidency, a decade earlier, had been marred by a controversy surrounding free expression and the closely related issue of student disruption. In September 1963, the Yale Political Union announced that it had invited segregationist Alabama governor George Wallace to speak. Just a few days earlier, a bomb had exploded in a black church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four African American children. Convinced that hosting Wallace would inflame tensions among New Haven’s African American population, Brewster met privately with students to urge them to rescind the invitation. New Haven mayor Richard Lee, then running for reelection, publicly announced that the governor was “officially unwelcome” in the Elm City. When the Political Union publicly retracted its offer, Kingman Brewster issued a press release stating that he was “grateful” for the students’ self-censorship. To many in 1963, it appeared that Brewster had caved both to Lee’s pressure and to the threat of violence, choosing to pragmatically sacrifice the principle of free expression to prevent bloodshed. Some trustees questioned his fitness as president, given his failure to artfully navigate the incident. According to Brewster’s confidant and right-hand man, Henry “Sam” Chauncey Jr. ’57, the experience deeply affected his boss. In later years, when making a “major institutional decision,” Kingman would often tell his assistant, “I’ve got to make sure I don’t make the kind of mistake I made in the Wallace case.” The following year, students at the University of California at Berkeley formed the Free Speech Movement, grafting the tactics perfected in the civil rights movement onto the political causes of the New Left. Questions quickly arose over the boundaries of free expression at American colleges. Did direct action—heckling a lecturer or orchestrating a sit-in—constitute a form of protected speech? Did everyone have a right to speak, including bigots whom some students wanted to bar from campus? How should universities treat those students who occupied a building to agitate for political demands? Yale actually defied the national trend of unrest until November 1969. Classics professor and former Yale College dean Donald Kagan later remembered that the university seemed like “the one place in the country where things seemed to be in good control.” When he accepted a faculty position in New Haven, Kagan’s colleagues at Cornell told him how lucky he was to be moving to a stable university. They particularly admired Yale’s firm and vocal stance against disruption, embodied in a document published in the spring of 1969.  Manuscripts and ArchivesC. Vann Woodward (left) was a well-known advocate of free speech when President Brewster (right) appointed him to chair the Committee on Free Expression at Yale. View full imageThat document, known as the “Brewster scenario,” started as a thought experiment in how the Yale administration would handle disruptive student-led direct action: the president would propose meeting with protesters to address their requests. If students rejected the offer to meet, they would be “subject to immediate suspension.” And if, even after suspension, students continued to interfere with university personnel and property, administrators would call the campus police. On paper, the scenario advertised a self-described “hard-line” yet pragmatic approach to disruption that combined a commitment to discipline and civility with a tone of respect for student radicals. Unfortunately, Brewster’s plan disintegrated upon its first contact with reality a few months later. When the university fired a black dining hall worker after an altercation with a manager, 60 students protested her dismissal by occupying her bosses’ offices in the basement of Wright Hall. With Brewster on a Caribbean vacation, the job of defusing the situation fell to Chauncey and provost Charles Taylor ’50, ’55PhD. The two men were flummoxed—they had expected protests at major university buildings, not an obscure location like Wright Hall’s basement. In retrospect, Chauncey remembered, “we were kind of winging it.” Following the predetermined plan, they suspended 47 students who refused to leave the sit-in. In an unexpected twist, the university committee responsible for student discipline commuted the sentences, citing a desire to show “mercy.” Brewster’s scenario failed completely; the president was livid that his faculty had betrayed him. Between the Wright Hall affair and the Shockley incident five years later, Yale continued to see moments of unrest. Brewster came under increasing fire from both liberals and conservatives for failing to stand up to the tactics of disruption and for the values of open discourse. The most famous episode, May Day, saw the university cancel classes in 1970 when thousands flocked to New Haven to decry the trial of Black Panther leader Bobby Seale. Yale’s tactics helped avert violence, to be sure—just three days later, four students would be killed in protests at Kent State—but the decision to shut down was another departure from the “Brewster scenario.” Then in 1972, General William Westmoreland, the former commander of US forces in Vietnam, visited campus to deliver a speech at the Political Union. A pugnacious student crowd gathered to protest his talk; Westmoreland refused to take the podium out of fear for his safety. It was the Shockley affair in 1974, though, that forced Brewster’s hand. Major newspapers covered the incident, and the conservative iconoclast William F. Buckley Jr. ’50 penned a syndicated column critical of the university. The worst fears of free-speech advocates were confirmed when the university executive committee voted in May to allow 12 students suspended for heckling Shockley to return to campus in the fall. It seemed like Wright Hall in 1969 all over again—no serious penalties for disruption at Yale. To bolster his reputation, Brewster turned to the academic administrator’s time-tested solution: a committee. For the chair, he tapped C. Vann Woodward, a towering scholar of southern American history. Crucially, Woodward was also a lifelong advocate of free speech who openly disliked the student radicalism of the 1960s. Also on the committee was Robert Dahl ’40PhD, a political scientist whose groundbreaking study of New Haven politics—Who Governs?—offered a much-admired defense of democracy. In the Yale pantheon, these men were Olympians, respected by liberal students and faculty alike. When the president offered Woodward the chairmanship in 1974, the historian expressed reservations, claiming he was far from impartial on the topic at hand. Brewster replied that Woodward’s public stance against disruption was not an issue. The subtext: the university needed someone to reaffirm its most basic values in the wake of the Shockley incident. On those terms—defending “the principles of free speech”—Woodward happily accepted the job. The committee included 13 members, with faculty, students, alumni, and staff all represented. The soon-to-be dean of the Law School, Harry Wellington, found himself on the list. Another committee member, the powerful Washington lawyer and alumnus Lloyd Cutler ’36, ’39LLB, was a close friend of Brewster’s. He slept at the president’s house when he was in New Haven, and he had helped orchestrate a university fund-raising campaign. During the 1974 fall semester, Woodward and his committee researched widely and debated the issues in their meetings, sometimes for hours. When it came time to compose their findings, the 13 divided assignments based on their personal interests. To Dahl fell the job of crafting a philosophical defense of open discourse, what is today the memorable first section of the report. Woodward and a student, Steven Benner ’76, volunteered to write a history of free speech incidents at Yale since 1963, what became the report’s second section. The third and final section, spearheaded by Wellington and Cutler, offered a series of recommendations for how Yale should handle potential disrupters and controversial speakers. After consulting with Woodward, Benner composed the first draft of a history. In Benner’s words, his initial narrative “did not pull any punches” and was critical of Yale’s failure to protect open discourse during the past decade. When the two presented their draft to the larger committee, Cutler balked. According to another committee member, Philip Sirlin ’74MA, Cutler told Woodward, “You can’t write this. If you write this, Kingman Brewster will have to resign.” Then the Washington lawyer “bullied Woodward” into rewriting the narrative. But Benner’s memory of the incident is different. He says that while Woodward did eventually “soften” the history, it was not necessarily to “accommodate Lloyd.” Instead, the historian applied “his professional pen to edit an unprofessional draft” by a young science student unskilled in writing history. In any case, after Woodward’s editing, the report’s narrative was much more favorable to Brewster. At least two free-speech incidents at Yale were omitted, as was the Wright Hall sit-in. May Day was held up as an example of open discourse, when at the time, Woodward had privately criticized the president. While it noted some of Brewster’s mistakes, the report deftly elided others. We are left with a series of unanswerable questions: why did Woodward soften the report’s historical narrative? Did he cave to Cutler’s pressure, or did he dilute the draft on his own initiative? Did the report represent the historian’s true beliefs, or did it reflect a realpolitik decision to protect Brewster from criticism? Regardless of the answers, there was a deep irony in one of America’s most respected historians censoring the past to defend free expression for the future. In the final analysis, Woodward and his colleagues’ practical recommendations were not revolutionary but conformed closely to the 1968 Brewster scenario. The committee advocated suspension or expulsion for student disrupters, the penalties already prescribed by the university’s existing regulations. Still, the report seemed groundbreaking in 1975. According to Woodward’s later recollections, the committee’s product “was certainly regarded as new.” More importantly, though, “it was a forceful description of what was going to be policy, what the purpose of the policy was, and what the purpose of the university was.” Heralded by the New York Times and others as a must-read for all academics, the report became a model for schools around the nation. It is the striking prose—the promise of “unfettered freedom” by Robert Dahl—that makes the Woodward Report a timeless document. We remember Dahl’s challenge “to think the unthinkable,” returning to those words in each successive decade for their clarity and moral guidance. Judge Jose Cabranes ’65JD and Yale law professor Kate Stith write that the report has achieved a kind of “constitutional status” at the university, transcending the moment in which it was written and its initial purpose. Yet behind all constitutions lies a history. For Woodward, Brewster, and their peers that was a history of academic high politics in the age of American unrest.

The comment period has expired.

|

|