loading

loading

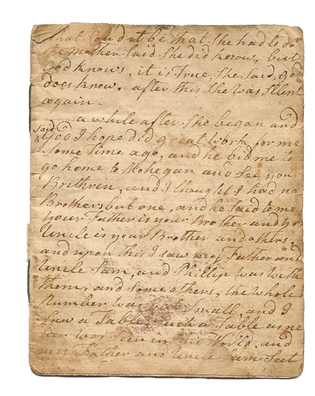

Arts & CultureDeathbed testamentObject lesson: an eighteenth-century Native American manuscript uncovered. Paul Grant-Costa ’08PhD is the executive editor of the Yale Indian Papers Project (YIPP), based at Yale Divinity School. Tobias Glaza is assistant executive editor of YIPP.  Courtesy Thomas Leffingwell House MuseumOn this page from a 1776 manuscript (shown close to actual size), a dying Mohegan woman describes the vision that led her to return to the reservation: God "bid me to go home to Mohegan and see your Bretheren...and upon this I saw my Father and Uncle Sam...and I saw a Table, such a Table as never was seen in this World." View full imageAs we carefully unfolded and examined the pages of an anonymous eighteenth-century manuscript last October, something about it struck us as familiar. Perhaps it was the handwriting, or the distinctive style and choice of words. Those were the elements that would eventually lead us to identify the author as Samson Occom (1723–92), a noted Mohegan clergyman and educator and the first Native American to publish an autobiography. The document, which is in the archives of the Thomas Leffingwell House and Museum in Norwich, Connecticut, includes the last words of a dying Mohegan woman. Occom had been converted to Christianity by the preaching of James Davenport, Class of 1732. He became a pupil of Eleazar Wheelock, Class of 1733, and was preparing to enter Yale College, but poor health changed his plans. Ordained in 1759, he served as a missionary to Indian communities in the Northeast. With other indigenous intellectuals, Occom became a leading figure in a New England Native cultural renaissance. In 1776, when the manuscript we found was written, Occom was 53. His travels had been restricted by the outbreak of the American Revolution, and he spent considerable time dealing with matters on the Mohegan reservation. That December, a daughter of Mohegan leader Robert Ashbow, motivated by a religious vision, returned home after what appears to have been a long absence. By the end of the month, the young woman was dying. On Christmas Eve, Occom wrote an account of the last moments of her life, which included a conversation with her mother. (The daughter’s name, unfortunately, is never given.) The beginning is typical for Christian deathbed narratives—a confirmation of belief in God and an acceptance of death. But then the woman declares, “No one that fights Shall ever enter the Kingdom of Heaven, nor them that Cary Sharp Weapons and Heavy things for the first Christians did not fight but were Loving.” She adds that her aunt Hannah thought herself “better and above” Hannah’s daughter-in-law, Jerusha, but Jerusha had “better inheritance.” These are unusual, unexplained statements. At first, we thought “inheritance” referred to spiritual redemption. But as we reconstructed the lives of the people in the narrative, another explanation seemed plausible. Hannah’s husband, we found, was Rev. Samuel Ashbow, Robert Ashbow’s brother. The couple had lost one of their sons, Samuel Jr., at Bunker Hill—the first Native American killed in the Revolution. For Hannah and Samuel, that death would begin their family tragedy: they would lose three more sons before the war was over. On the other hand, Jerusha, the widow of Samuel Jr., had a young son whose life was just beginning. Were the dying woman’s remarks a comment on the futility of war? A portent of the immense physical and cultural losses the Mohegans would endure as a result of that war? Perhaps. It is interesting to speculate. These deathbed utterances are not typical of Occom’s other writings. We believe that he wrote the piece to give as a memorial to Robert and Samuel—who were away from Mohegan, most likely on a missionary tour—and that he may have done so at the behest of the dying woman or her mother. Consequently, the account is more intensely personal and intimate than it might otherwise seem, a gift celebrating the life and death of the daughter and niece of two of Occom’s close friends and mentors. |

|

1 comment

-

Joe Bauman, 2:28am March 22 2015 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.I enjoyed reading this, but would have enjoyed it much more if a transcription of the manuscript had accompanied it. At the least, the entire document should have been shown. But thank you for an interesting read. -- Joe Bauman