loading

loading

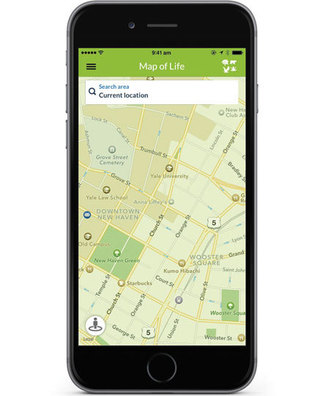

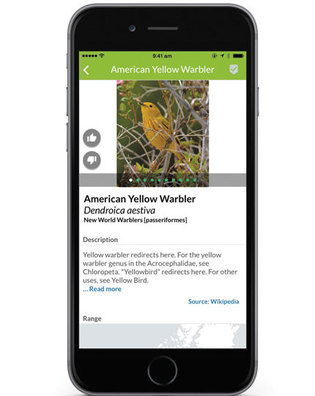

Arts & CultureLife? There’s an app for that.Object lesson: a field guide that knows what that bird (or frog, or tree) could be. Walter Jetz, an associate professor in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and adjunct professor at the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, led the development of the Map of Life app. To learn more, visit http://mol.org or look for the free app at http://mol.org/mobile or in the Apple or Android app stores.  View full image View full image The Map of Life app draws on scientific literature and public databases to deliver authoritative natural history information on species known to be in your area. View full imageWhen the ornithologist and painter Roger Tory Peterson published the first modern field guide in 1934, he solved one of the biggest problems in species identification. No longer was it necessary to shoot or catch a creature and take it to an expert to find out its name; all you needed was the Field Guide to Birds (or one its many successors, which cover all sorts of living creatures)—along with sharp eyes, patience, and fast fingers to turn the pages. Now, thanks to smartphones and “big data,” an effort is under way to create field guides that can tell you what’s around even before you lift the binoculars or the magnifying lens. A field guide of this sort was recently launched by Map of Life, an international research effort headquartered at Yale’s Program in Spatial Biodiversity Science and Conservation. The Map of Life app shows what kinds of life surround you, no matter where you are in the world. When you request information on a particular group (mammals, birds, amphibians, trees, wildflowers, turtles, dragonflies, butterflies, or fish—a collection that is growing rapidly), the app delivers an inventory of all the species believed to be in your area. It also provides images, range maps, and authoritative natural history information, so you can satisfy your curiosity about the frog or butterfly you just glimpsed. The data are culled from scientific literature and public databases, along with satellite remote-sensing, so the app is constantly updated. The predictions of where and when species may occur are generated using the latest modeling techniques. The app also makes the study of natural history more interactive. Therein lies great scientific utility. The gaps and uncertainties in our data on spatial biodiversity can be huge, and they put constraints on scientific undertakings such as assessments of species status and trends, monitoring of species invasions, resource management, and ecological research. Changing environments and species losses and invasions are on the horizon, yet there is no satellite system or other system to monitor these perturbations and few means for biologists to assess and predict the consequences. But detailed observations from individuals, especially in understudied regions, could advance our knowledge significantly. Armed with mobile technology, amateurs can become citizen scientists, sharing their observations and helping to fill in the gaps. Your hike into the woods, the desert, or the prairie could become an invaluable resource for our global and local understanding of biodiversity.

The comment period has expired.

|

|