loading

loading

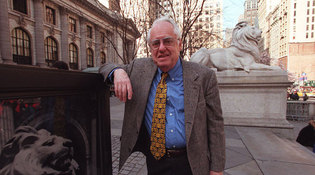

MilestonesPeter Gay, 1923–2015A giant of European cultural history who cared about people.  Marilynn K. Yee/The New York Times/ReduxPeter Gay, seen here in a 1999 photo, was known for his work on Freud. View full imageWhen Peter Gay, the Sterling Professor of History Emeritus, died on May 12 at his home in Manhattan at the age of 91, Yale and the world lost a towering intellect in the exploration of European cultural ideas, from the Enlightenment to the Victorians, from the bourgeois experience to Sigmund Freud. Author of more than 25 books, Gay was “tremendously influential, tremendously admired,” says David Sorkin, the Lucy G. Moses Professor of Modern Jewish History. Born Peter Joachim Fröhlich in Berlin in 1923 to atheist parents who rejected their Judaism, he was raised in comfortable circumstances—until the rise of the Nazis. The family fled for their lives in 1939, settling first in Cuba and then, two years later, in Denver. There, because his last name was hard to pronounce, he changed it to Gay, the English equivalent. He graduated from the University of Denver in 1946 and earned his PhD in 1951 at Columbia, where he taught until he joined the Yale faculty in 1969. Gay is probably best known for his beautifully readable 1988 biography of Freud, whose ideas prompted him to study psychoanalysis and apply its tenets to the examination of history. Gay won the National Book Award in 1967, for The Enlightenment, and he won the American Historical Association’s lifetime achievement award in 2004. In 1993, Gay became one of the last Yale professors to be forced into retirement at age 70 (under a rule that has now been discarded). However, he hardly retired, continuing to teach, mentor graduate students, and hold court at Yorkside Pizza. “He just cared about people, not just vaguely in the abstract but on a day-today basis,” history professor John Merriman told the Yale Daily News. From his adopted home in New York City, Gay also continued to write books, including, most recently, Why the Romantics Matter, an examination of the foundations and impact of European culture from the eighteenth century onward; it challenges accepted wisdom on both Romanticism and Modernism. “All generalizations are wrong,” he once told a New York Times reporter. “That’s why I find being an historian so interesting.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|