loading

loading

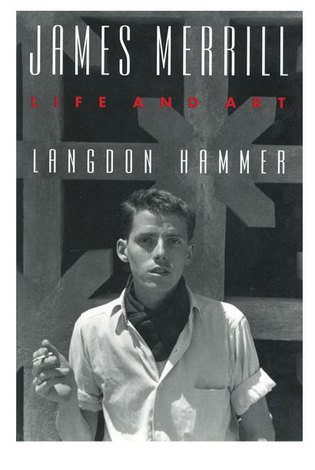

Arts & CultureReviews: November/December 2015Books about James Merrill, the Wright Brothers, and the origins of the “blood libel.”  View full imageJames Merrill: Life and Art Rebecca Steinitz ’86 is a Boston-based literacy consultant, editor, and freelance writer. The son of the founder of Merrill Lynch, Merrill was born in 1926. He wrote his first poem at 6, saw his first opera at 11, first fell in love with a man at 19, and debuted in Poetry at 20. These early experiences set him on his life’s path. Cushioned by his father’s money, he devoted his work to poetry and his leisure to opera, travel, and socializing. Endlessly seeking love and sex (perhaps as a consequence of his parents’ ugly divorce), he eventually settled into a fraught but enduring four-decade relationship with would-be author David Jackson, even as he pursued casual encounters and numerous love affairs on the side. Merrill juggled homes and social circles in Connecticut, Athens, and later Key West, and he became a celebrated poet, winning Bollingen, National Book Award, and Pulitzer prizes before dying in 1995 of the AIDS he had carefully hidden. Hammer, chair of the Yale English department, threads his detailed account of Merrill’s life with meticulous close readings of the poems—not surprisingly, for the two were inextricably interrelated. The formalist lyrics, complex longer poems, and The Changing Light at Sandover (an experimental epic based on Jackson and Merrill’s four decades of communicating with spirits through their Ouija board) emerged from and also transmogrified Merrill’s life, even as they were shaped by his love of language and the play of words and sounds. Hammer, a superlative researcher and elegant writer, is acutely attuned to the biographical and literary nuances of both life and art. He has written a twentieth-century biography for the ages.

|

|