loading

loading

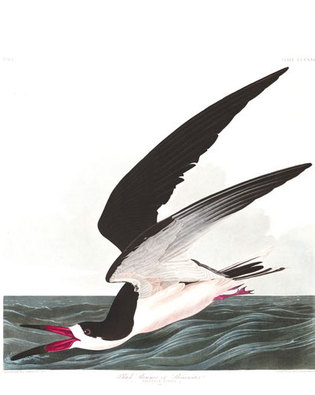

featuresAudubon’s works, off the endangered listA tale of salvation: how some of the remaining copper plates of Audubon’s Birds of America were rescued. Geoffrey Giller MESc ’14 is a freelance science writer currently living in Ithaca, NY. His work has also appeared in Scientific American and Audubon.  National Audubon SocietyA print of John James Audubon’s Black Skimmer or Shearwater, made from one of five original copper plates now in the Yale Peabody Museum’s collection. The plates, created for Audubon’s monumental book Birds of America, were engraved in the early nineteenth century, measure around two by three feet, and weigh up to 37 pounds. View full image National Audubon SocietyView full image Yale Peabody Museum of Natural HistoryThe plate (with above print) of the Black Vulture, which was narrowly saved in 1873 from being melted down. Yale has two original sets of Birds of America; two volumes are on display at the Peabody through July 2016. View full image Yale Peabody Museum of Natural HistoryThe copper plate of the Black Skimmer, showing fingerprints that can’t be removed without damage. View full imageIn 1873, a teenaged budding ornithologist named Charles Cowles noticed something strange at his father’s copper refinery. On one of the tarnished copper sheets a worker was about to toss into the furnace, Cowles saw, as he later wrote, “what appeared to me to be a picture of a bird’s foot.” He rescued the plate and cleaned it with acid, revealing the image of a vulture. It’s not clear from his account, published as part of a 1908 article in the ornithological journal The Auk, whether he immediately recognized what this was: one of the original copper plates commissioned by John James Audubon to print his famous double-elephant folio, Birds of America. In any case, Cowles desperately set about trying to save the other plates, pleading first with the foreman, then the superintendent, and finally his father the general manager. “I received no encouragement,” he wrote. But he still managed to spare the plates long enough to show them to his mother, who recognized them for what they were. Originally, there were 435 copper plates created to print Birds of America, almost all of them meticulously engraved by Robert Havell Jr. of London between 1827 and 1838. (William Lizars engraved the first ten before some of his workers went on strike.) The plates are massive, around two feet by three feet and weighing as much as 37 pounds. Today, only about 78 plates remain, according to a 1974 cataloging. Some were lost during Audubon’s lifetime; a large fire in New York City destroyed the warehouse where they were stored, and at least a few couldn’t be restored “to their wonted former existence,” as Audubon wrote in an 1845 letter. There’s also a story that a ship transporting the plates from London to New York sank in the New York harbor—though this particular misfortune seems to be apocryphal, according to a 1966 Audubon magazine article by Waldemar Fries. (Fries spent years studying Birds of America, eventually writing a detailed history on it.) But most of the plates survived until after Audubon’s death in 1851. In 1870, in a trade publication for publishers, an ad appeared on behalf of Audubon’s widow, Lucy, listing 350 plates “of this magnificent work...to be sold to the highest bidder.” The next year, the New York Times reported that the plates had been sold “for their value as old copper, after having vainly sought a purchaser upon their artistic merits.” Thus, it seems likely that many of the plates suffered the fate that Cowles sought to avert: being melted down for scrap. Fries write that two at first escaped destruction because they were donated to a museum in Hartford, Connecticut—but that later, “in a costly moment of patriotic zeal,” the museum contributed them to a World War II drive for metal. Still, many plates were preserved. (Some turned up in junk shops.) The Peabody Museum has five: the Black Skimmer or Shearwater, Marsh Hawk, Herring Gull, American Scoter Duck, and the Black Vulture or Carrion Crow—the same plate Cowles saved from the refinery flames. Edwin Vare Jr. donated the five plates in 1955 while his son Ned was at Yale. In 1974, the Peabody issued a set of 500 prints made from an electroformed duplicate of the Black Skimmer plate. “The years have taken their toll on Havell’s beautiful etching,” a brochure noted. But “in spite of 136 years of wear and neglect the startling beauty of Audubon’s painting and Havell’s engraving is clearly seen.” Indeed, the plate itself, despite oxidized fingerprints at the edges and across the image, still displays the graceful lines of the skimmer as it lowers its beak to the surface of the waves in its unending search for fish.

The comment period has expired.

|

|