loading

loading

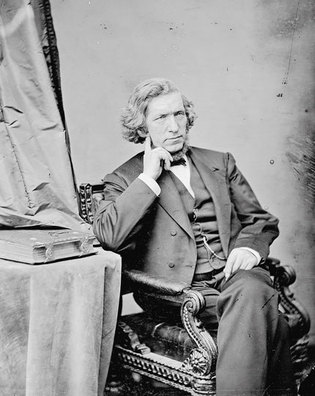

Old YaleYale’s first student from IrelandA Presbyterian, born in Belfast, who championed Catholics. Judith Ann Schiff is chief research archivist at the Yale University Library.  Wikimedia CommonsWilliam E. Robinson, Class of 1841, ’42Law—shown here in a Civil War-era photo by Mathew Brady—lived up to his middle name: Erigena, or "Erin-born." View full imageWhen William E. Robinson, Class of 1841, ’42Law, died in 1892, the Yale Obituary Record saluted his service as a US Congressman and his founding of the Yale Banner, which became the Yale College yearbook. In an unusually strong statement for the normally reticent Record, it also noted: “Both in his public and in his editorial utterances he was conspicuous for his hostility to the English government.” Surprisingly for an Irish patriot, Robinson was not a Catholic, but a Scots-Irish Presbyterian raised in the north. Born in Belfast in 1814 to a farming family, he studied at the city’s Royal Academical Institution, a secondary school and college established, a founder once said, to serve “the middling orders of society.” After an attack of typhus compelled him to leave school, Robinson worked on his father’s farm until, in 1836, he emigrated to live with family in New York. In his diary (now in Sterling Library), he described 52 “home-sick and sea-sick” days aboard the storm-tossed Ganges—and, once the ship reached Staten Island, a brief quarantine due to an outbreak of smallpox on board. When Robinson matriculated in the fall of 1837, he had nine dollars to his name. He supported himself at Yale by writing for the New Haven Herald—an early venture into journalism that would help shape his future career. He was active on campus, founding the Yale chapter of the Psi Upsilon fraternity (now defunct) as well as the Banner, which is still publishing. After graduating, he enrolled in Yale Law School, and in 1842 he was the featured orator at the first public celebration of St. Patrick’s Day in New Haven. His two-hour oration, published in a 67-page pamphlet, is a comprehensive course in Irish history and politics and the current state of Catholicism. It also stressed his admiration for Catholics as patriotic Americans, and included a plea to continue the policy of granting citizenship to immigrants after five years’ residence. “Let the term [of five years] remain settled,” he wrote; “let the controversy come to an end. After a proper residence, . . . let them be bound to the Republic by the strong tie of citizenship, and they will live or die for her liberty.” Robinson did not finish law school; in 1843 he toured America to lecture on Ireland, and in 1844 he campaigned for Henry Clay’s presidential bid. After leaving New Haven in 1844, he began writing for the New York Tribune, living in Washington and covering Congressional sessions under the pen name “Richelieu.” For the Tribune and other papers, he also wrote to boost awareness of and aid for the victims of the Irish potato famine, and for support of the Irish Rebellion of 1848. In 1854 Robinson began practicing law in New York City. He was elected to three terms in the US House of Representatives on the Democratic ticket, in 1866, 1880, and 1882. After his death in 1892, a fellow journalist recalled how Robinson had embraced the diversity of his chosen country—as a Protestant who spoke for Catholics and as a Union patriot who called for magnanimous treatment of the South: “He was an Irishman, and at the same time, and in its largest sense, he was an American.

|

|

1 comment

-

Joe Lynch, 5:42pm March 17 2016 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.Interesting read and man. Judith, any additional information re: "in 1842 he was the featured orator at the first public celebration of St. Patrick’s Day in New Haven". The New Haven St. Patrick's Day Parade began in 1842 on St. Patrick's Day.