loading

loading

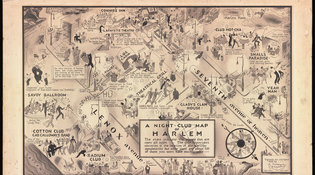

Arts & CultureA guide to club hopping in Harlem, circa 1932Object lesson: a whimsical map just acquired by the Beinecke Library. Melissa Barton ’02 is curator of drama and prose for the Yale Collection of American Literature.  Cab Calloway’s “HO-DE-HI-DE-HO” floats into the night in this detail from the Beinecke’s newly acquired 1932 Night-Club Map of Harlem. The 24-by-32-inch map, in ink and watercolor on illustration board, was the work of E. Simms Campbell, the first highly successful African American illustrator. View full imageIt was a time, wrote Langston Hughes, “when the Negro was in vogue.” In the 1920s and early ’30s, the arts flourished in Harlem, and African American artists in all genres flocked to uptown New York. What we now call the “Harlem Renaissance” became famous—and drew tourists. E. Simms Campbell’s 1932 Night-Club Map of Harlem serves as both guide and commentary on the time. Featuring Harlem’s storied venues, including the Cotton Club, Connie’s Inn, Smalls Paradise, and the Savoy Ballroom, the map offers advice to the same audience that Irving Berlin encouraged to head uptown in “Putting on the Ritz.” At Club Hot-cha, “nothing happens before 2 a.m. Ask for Clarence.” Tillie’s “specializes in fried chicken—and it’s really good!” Street vendors include the Peanut Man, the Crab Man, and the Reefer Man, who sells “Marihuana cigarettes” at two for 25 cents. Meanwhile, countless small moments comment on the craze for Harlem, as well as the lives of its residents. A crush of cabs delivers lavishly attired downtowners to Connie’s (which, like the Cotton Club, excluded African American customers). A “Sheik” arrives at Gladys’ Clam House with an entourage of women and dogs. A man tosses his top hat out the window for the use of a friend going out on the town. A door floating on the sidewalk is the only visible evidence of a speakeasy. Inside “the nice new police station,” policemen playing cards ask, “What’s th’ number?” Pairs of people all over the neighborhood are wondering the same thing: they’re hoping to win the daily lottery run by racketeer Casper Holstein. The flexibility of the streets’ geography—110th Street is pushed right up against 131st, and 142nd is squished in south of 138th—speaks to the neighborhood’s notorious overcrowding. Nodding to some of Harlem’s most celebrated entertainers, Campbell shows Bill “Bojangles” Robinson performing his famous stair tap dance. Gladys Bentley, who was known for playing songs thick with double-entendres, “wears a tuxedo and high hat and tickles the ivories” all night. At the Savoy Ballroom, called “the Home of Happy Feet,” couples dance the Lindy Hop, and Earl “Snake-hips” Tucker—whose movements inspired later hip-hop dance forms—defies anatomy. The largest figure on the map is Cab Calloway, whose “HO-DE-HI-DE-HO” floats out into the night. A close friend of Campbell’s, Calloway had the map printed as the endpapers to his 1976 autobiography, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me. Oriented with north pointing to the lower right, the map gives a window on Harlem that would have been novel for downtown readers of Manhattan: A Weekly for Wakeful New Yorkers (the periodical that published it in 1933). At the same time, the map also expects enough familiarity with the picture of Harlem represented here that readers would have been in on the joke. Elmer Simms Campbell, the first highly successful African American illustrator, studied at the Art Institute of Chicago before moving to Harlem in late 1929. He produced illustrations for the New Yorker, Cosmopolitan, and Playboy, as well as the African American journals Crisis and Opportunity, and he was staff illustrator for Esquire magazine. His Cuties cartoon was syndicated in more than 100 newspapers nationally. The Night-Club Map is unusual in that Campbell tended not to feature African American characters or life in his art, though he did write essays for Esquire on music and performance.

The comment period has expired.

|

|