loading

loading

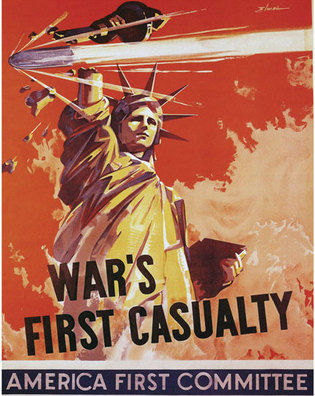

featuresThe forgotten antiwar movement75 years ago, Yale students founded a national organization. Its mission: to stop America from fighting Hitler. Marc Wortman is the author of 1941: Fighting the Shadow War: A Divided America in a World at War.  Getty ImagesThis detail from a poster printed by the America First Committee illustrates one of the organization’s main tenets: that if the United States entered the war that was raging in Europe, it would be catastrophic for American democracy. View full imageOn June 18, 1940, the world learned that Paris had fallen and the French army had capitulated to German forces. Hitler’s lightning conquest of Western Europe was complete. Yet June 18 would also prove a turning point in resistance against the forces of violent aggression. Public addresses by three men that day galvanized their nations and helped set in motion the forces that would eventually topple the Axis Powers. Two of those speeches came to be considered among the most important in modern history. “The Battle of Britain is about to begin,” Prime Minister Winston Churchill told the House of Commons. “If we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new dark age. . . . Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour.’” Broadcasting that evening over the BBC from London, a then relatively obscure French general, Charles de Gaulle, also emphasized the global character of the war. “France is not alone” in its darkest hour, he declared, launching Free France, the national army-in-exile. “Like England, [France] can make unlimited use of the vast industries of the United States. . . . This war is a worldwide war.” The third speech is little known today. A few hours after de Gaulle and Churchill spoke, a radio address broadcast from a house near Yale University challenged Americans to respond to the unfolding catastrophe. The man who addressed the nation, Henry L. Stimson ’88, was a private citizen at the time but had held numerous federal posts and was widely regarded as the country’s elder statesman. At age 72, the slender, mustachioed Stimson—an “impossibly grand figure,” as journalist Joseph Alsop wrote—was the very model of the leadership coterie that Alsop dubbed “the WASP Ascendancy.” And he was a war hero: in 1917, at age 49, the former secretary of war had enlisted in the Army, leaving his law firm and his wife, to serve as head of an artillery regiment on the Western Front in France. On the evening of June 18, he told listeners that their country faced “probably the greatest crisis of its history.” In the emergency “which strikes at the very existence of all that our nation has cherished and fought for,” he said, the danger was clear: should Britain fall and Germany take its fleet, “our men would soon be fighting for their own and our lives on American soil.” Stimson called for the repeal of the neutrality laws that Congress had designed in the late 1930s expressly to keep the nation from being drawn into the impending European wars; the country, he said, should rearm the British and open US ports to their warships for repair, fueling, and resupply. He also called for an immediate, compulsory national military draft. That was a startlingly radical notion: in its 164-year history, the United States had never conscripted citizens except in times of war. “I believe,” he concluded, “we should find our people ready to take their proper part in this threatened world and to carry through to victory, freedom, and reconstruction.” Some students listening to Stimson over the radio that evening at Yale wondered, Victory for whom? Whose freedom? The country had already done all that in Europe barely a generation ago. Rather than fight another cataclysmic and inconclusive war, many in this generation were hell-bent on staying home.

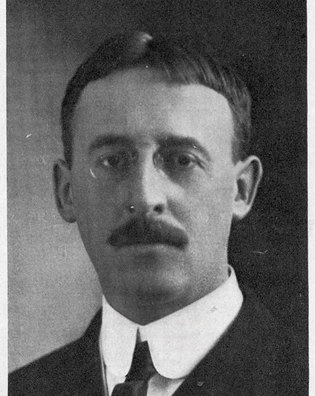

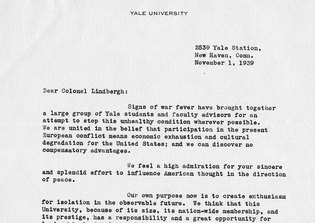

Manuscripts and ArchivesOn June 18, 1940, former Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson ’88 told the nation that if Britain fell, Americans “would soon be fighting for their...lives on American soil.” View full image Courtesy Library of CongressCharles Lindbergh (center) with future Yale president Kingman Brewster Jr. ’41 and Richard M. Bissell Jr. ’32, ’39PhD, an assistant professor of economics (later the CIA’s deputy director for plans). View full imageThe issue of war or peace for Americans at this moment marked a generational divide unlike any before in US history—a schism that would be seen again 25 years later, when another youthful generation would be called upon to fight a distant war. Stimson’s call to the nation crystallized the desire of an influential group of Yale students to oppose intervention. The editor of the Yale Daily News, Kingman Brewster Jr. ’41, declared in an editorial that, as “the ones to man whatever first line of defense” the nation decided on, they had “more right than ever before to have a word in the choice.” His choice was against war. In a series of meetings held at Yale Law School just days after Stimson’s address, Brewster joined a group of law students who had already started gathering to oppose US intervention. Together they launched a new campus organization. Taking the lead in those meetings were Brewster and Robert Douglas Stuart Jr. ’46JD. Stuart, a law student and natural organizer, handsome, tall, and personable, came from Chicago, where his father had founded and now headed the cereal maker Quaker Oats. Brewster, a Mayflower descendant, was the ideas man, preternaturally mature and articulate (and perhaps a little full of himself: he arrived at his Daily News office each day in a three-piece suit with a gold watch fob across his vest). He had rejected selection to Skull and Bones on principle, considering the organization undemocratic. Other students on hand included a veritable who’s who of future leaders—among them an eventual Supreme Court justice, Potter Stewart ’37, ’41LLB; Peace Corps founder Sargent Shriver ’38, ’41LLB; and President Gerald Ford ’41LLB. Most were from privileged family backgrounds, Republican by political party, and social liberals within the limits of their elite sphere. All shared Brewster’s conviction that, as he and his Harvard Crimson counterpart, Spencer Klaw, wrote jointly in the Atlantic in September, the right path for the nation was to “take our stand here on this side of the Atlantic, precarious as it is, because at least it offers a chance for the maintenance of all the things we care about in America, while war abroad would mean their certain extinction.” Over the summer, Stuart and Brewster gained the support of national Republican leaders. Among them was Robert A. Taft ’10, Ohio’s deeply isolationist Republican senator, the son of the former president and a man widely considered presidential timber. Robert E. Wood, chair of Sears, Roebuck, a West Pointer and World War I quartermaster general, agreed to serve as chair for the new national Committee to Defend America First—to be headquartered in Chicago, Wood’s hometown, with Stuart as director. Wood asked members of Chicago’s wealthy business community for support; in response, many wrote big checks. Most important, the Midwest’s most influential publisher, Colonel Robert J. McCormick of the Chicago Tribune, made his newspaper an isolationist loudspeaker. Before the young Elis returned to campus in the fall, America First, now a national organization embracing all comers “who want to keep out of the European war,” began to rally adherents to its cause. The organizers mimeographed a letter that went out to other campuses, setting out their founding principles: building “an impregnable defense for America,” preserving US democracy “by keeping out of the European war,” and reserving US might and resources because “aid short of war weakens national defense at home and threatens to involve America in war abroad.”

Manuscripts and ArchivesEven before the America First Committee was formed, several Yale students, concerned about “participation in the present European conflict,” had reached out to Lindbergh. View full image Ralph Morse/Getty ImagesProtesters march outside the national headquarters of the America First Committee in Chicago. View full imageBob Stuart left law school to devote himself full-time to America First. He started by recruiting nationally known figures to the board. Among those who signed on were General Hugh Johnson, who had overseen conscription in the Great War; the wives of Senators Burton K. Wheeler and Bennett Champ Clark, whose husbands would become popular speakers at America First rallies; Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas; actress Lillian Gish; liberal New Republic columnist John T. Flynn; and University of Chicago president Robert Maynard Hutchins ’21, ’25LLB. (Auto industry titan Henry Ford also joined for a few months, despite Stuart’s trepidation over his well-known anti-Semitism.) Others who helped to grow the organization into a national movement included three of Teddy Roosevelt’s children; Joseph Kennedy Jr., son of FDR’s former ambassador to Great Britain, and his younger brother John; and Republican stalwarts Herbert Hoover and New York Daily News publisher Joseph Patterson. Before fall, the Committee for America First began operations out of its Chicago national headquarters, planned rallies and mail campaigns, and had enough money in its coffers to run full-page ads in nearly every major newspaper in the country. Soon America First chapters were popping up across the land.

One man, however, transformed America First into the most powerful antiwar campaign in US history. Since before the war began, Charles Lindbergh had been as determined, disciplined, and skilled in his drive to keep the United States from going to war in Europe as he was in flying solo between the continents. Impressed by Germany’s rapid progress in aviation during two visits there, he had made plans to move to Berlin, but returned home before Germany invaded Poland in September 1939. In the first year and a half of the war, he made five nationwide radio broadcasts, addressed two large public meetings, published three articles in popular magazines, and testified twice before congressional committees. Anne Morrow Lindbergh, his wife and a noted author, came to the defense of German fascism in her number-one best-selling 1940 testament, The Wave of the Future: A Confession of Faith. Nazism and other movements crushing human freedom, she wrote, were just “scum on the surface of the wave” as civilization moved fitfully into a new “highly scientific, mechanized, and material era.” A week after Germany’s May 10, 1940, invasion of the Low Countries, Charles Lindbergh told a national radio audience that America had nothing to gain and everything to lose by intervening. He urged the nation to secure its own borders, which in any foreseeable scenario, he said, remained beyond invasion. “If we desire peace,” he insisted, “we need only stop asking for war. No one wishes to attack us, and no one is in a position to do so.” He warned that certain unspecified groups within society lay behind the drive to join forces with the British against Hitler and the fascists. He told millions of listeners: “The only reason that we are in danger of becoming involved in this war is because there are powerful elements in America who desire us to take part. They represent a small minority of the American people, but they control much of the machinery of influence and propaganda. They seize every opportunity to push us closer to the edge.” Ultimately, he contended, a national spiritual rebirth, a change in outlook adequate to a revolutionary age of technology and social organization, was key to the nation’s future: “It is time,” he declared, “for the underlying character of this country to rise and assert itself, to strike down these elements of personal profit and foreign interest.” Listeners realized he was speaking primarily about Jews (though he also later referred to British nationals living in the country). Lindbergh’s isolationism meshed with America First’s program; his heroic past made him an American icon. Bob Stuart tagged him as the group’s potential leader. Stuart attended an August 4, 1940, dinner for Lindbergh at publisher McCormick’s home and talked with Lindbergh at length. The next day, he dashed off a letter asking the Lindberghs to help their movement “give sane national leadership to the unexpressed conviction of the majority of American people that this is not our war. ‘Defend America First’ will be our theme.” Lindbergh liked the young man, and he appreciated the group’s nonpartisan stance—welcoming liberals and pacifists along with Lindbergh’s own reactionary brand of support for neutrality. A few months later, he formally joined America First.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesLindbergh formally joins the America First Committee. He is sitting with Bob Stuart ’46JD, who had left Yale Law School to serve full-time as America First’s national director. View full image Manuscripts and ArchivesLindbergh at a reception in Germany, circa 1937. View full imageA national spotlight now illuminated antiwar activities at Yale. History professor Arnold Whitridge ’13, grandson of English poet Matthew Arnold, had volunteered for the British in 1915 and then joined the US Army when it arrived two years later. Appalled by student “indifference” to the fate of democracy and freedom in Europe, he wrote an “open letter to American undergraduates” that ran in the Atlantic in August 1940. Students were “hovering on the sidelines,” he wrote, “most of you still contemplating the tragedy of Europe as something interesting but remote. You seem to me to be suffering from a sluggish imagination and arrested skepticism.” The next month, Yale’s internationalist president, Charles Seymour ’08, ’11PhD, offered a more circumspect view in the New York Times Sunday Magazine. He blamed student isolationism on the trend by which “suspicion of idealistic proposals” had turned “into the most extreme cynicism.” He thought the nation’s elders had yet to clarify the stakes for the country sufficiently. He was also relieved that the question of selective service had come up during summer vacation—which “saved us a good deal of debate on our college campuses.” The debates and protests would come soon enough—in larger spheres than campuses.

The hotly contested 1940 presidential race pitted FDR against Republican Wendell Willkie. Late in the race, Willkie veered into the isolationist camp—turning the election into a referendum on FDR’s interventionist foreign policy. With the vote just a week away, the moment had come for Lindbergh, perhaps the most famous man on the planet, to step forward. He chose to speak at Yale. On October 30 he came to New Haven to address the Yale community in Woolsey Hall. By coincidence, FDR’s train made a campaign whistle stop in New Haven on the same day. FDR had by now brought Stimson on as his secretary of war, and together they had pushed through legislation to carry out the most controversial proposal in Stimson’s June 18 radio talk: creating the nation’s first peacetime conscript army. On October 29, with just one week remaining until the election, and with the president watching, Stimson had pulled the first selective service lottery number of a projected 800,000 draftees. Many voters were deeply disturbed by the involuntary military call-ups. As rain showered Union Station’s platform and tracks, the president came out of his railroad car to give a short speech. He sought to reassure the audience—some 2,000 people, most of them union members, almost none of them students—that the draft did not presage war. “We have started to train more men,” he proclaimed, “not because we expect to use them, but for the same reason your umbrellas are up today—to keep from getting wet.” The crowd laughed, but behind the scenes FDR was troubled. Lindbergh, America First, and millions of ordinary people who supported them were forcing him to retreat from open support for intervention, even if it meant the fall of Great Britain. That same night, Yale students turned out in droves to hear Lindbergh. Woolsey could seat 2,700, with standing room for a few hundred more. Lindbergh noted, “Every seat was taken, and people were standing along the walls.” Richard Ketchum, a Yale student, wrote later: “You could feel the electricity [in] the sheer magnetism of his presence.” He was “our boyhood hero, . . . the personification of the air age that was shaping the destiny of our generation. . . . He probably knew more about the strengths and weaknesses of the air forces now locked in combat in Europe . . . than any man alive.” Brewster, as head of Yale’s America First chapter, made opening remarks. (Lindbergh would recall him as “interesting, honest, and able, although slightly inclined to be theatrical.”) Lindbergh rehearsed many of his standard themes, telling the students that no nation on earth would dare cross the Atlantic to attack. However, US intervention in Europe would be “a disaster for both our country and Europe.” America should pursue its “independent destiny,” he warned: “We must either keep out of European wars entirely, or participate in European politics permanently.” As if his audience might forget, he reminded them of the draft begun the previous week, and said they would be called to fight should their nation go to war. The evening’s reception delighted Lindbergh. He had anticipated the protests that accompanied his previous public events. Instead, “they listened attentively during the entire half hour,” he wrote in his journal afterward, “and it seemed that everyone in the hall was clapping after I finished! Although it was not large, it was by far the most successful and satisfying meeting of this kind in which I have ever taken part.” That same night, FDR made a speech in Boston. With Willkie gaining in the latest polls, Roosevelt made a promise to the crowd and a national radio audience: “Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.” The line drew his loudest applause of the night. Learning about the success of Lindbergh’s speech and FDR’s flat-out noninterventionist declaration that same evening, General Wood sent congratulations to Lindbergh: “We have forced the administration in power to come out with some very strong statements which it will be hard for them to repudiate after the election even in the event they are successful.” Indeed, the man who helped shape many of FDR’s speeches in the period agreed. Robert Sherwood wrote later that “the isolationists’ long and savage campaign . . . exerted an important effect on Roosevelt himself: whatever the peril, he was not going to lead the country into war—he was going to wait to be pushed in.” Lindbergh became America First’s principal spokesman in spring of 1941. The organization’s membership exploded. He gave 13 speeches at rallies from coast to coast, drawing raucous crowds that rivaled major sporting events, with millions more listening in on the radio and seeing him on newsreels. A Chicago talk brought out close to 40,000 people. So many turned out for an America First rally at New York City’s Madison Square Garden that 20,000 people who couldn’t get in filled the streets outside to listen to Lindbergh over loudspeakers. The committee soon claimed more than 800,000 dues-paying members in 450 chapters, making it the largest antiwar organization in American history and by far the most wide-reaching campus-launched movement.

Yale Daily NewsThe Yale Daily News made Lindbergh’s October 30, 1940, speech in Woolsey Hall its headline the next day. In the photo, Lindbergh is at the lectern. He was warmly received; the Yale Alumni Magazine reported, “It was obvious from the moment that Lindbergh rose to speak that he was among friends.” View full image William C. Shrout/Getty ImagesTen thousand people attended this rally of the America First Committee in the Chicago Area. View full imageIn January 1941, FDR pushed for Lend-Lease legislation, which would empower him to sell or “loan” American-made ships, aircraft, and other munitions to any nation he deemed “vital” to US defense. Meanwhile, news from Europe was moving many isolationists to reconsider: the German war atrocities and anti-Semitic acts, the Blitz in England, the slow strangulation of Atlantic trade through the U-boat campaign. Before the summer of 1940, a large majority of Yale students, when asked, had indicated little willingness even to increase aid to the Allies. Now, a shift had taken place. A Yale Daily News poll of students during the Lend-Lease debate found that 75 percent favored aid to England. Respondents were almost evenly split on their willingness to risk war. Professor Arnold Whitridge—who had previously excoriated student indifference in the Atlantic—told the newspaper, “there has been a definite change in undergraduate sentiment since last spring. Isolationism is a dead issue.” A well-organized minority of students continued to disagree. Some were Communist Party members aligned with the Soviet Union’s nonaggression pact with Germany, some were pacifists, but most shared the America First view that the United States would be drawn into a doomed war effort that would demolish democracy at home. Brewster made that argument as the first member of his generation to speak before Congress about the Lend-Lease bill. He told members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that students trusted Lindbergh and respected his “courage and straightforwardness.” As for FDR, “we are resentful of the deceit and subterfuge which has characterized the politics of foreign policy.” Although Brewster insisted his generation would fight if called, he contended that “fundamentally . . . the peace of this hemisphere has more to offer the world of tomorrow than any possible outcome of a devastating transoceanic war.” As for Lend-Lease, “unless you want to go to war—in which case dictatorship seems inevitable—I can see no justification for such a sweeping grant to any one man. . . . We resent the effort to hide from the American people tomorrow’s consequences of what we do today.”

The Lend-Lease bill passed on March 31, 1941. Its enactment forced many of those opposed to intervention to change their views. For the upright Brewster—perhaps America’s best-known student-isolationist—the choice was clear: he resigned from the organization he had helped to found. He wrote to Bob Stuart, still national director of America First, “Whether we like it or not, America has decided what its ends are. . . . A national pressure group therefore is not aiming to determine policy, it is seeking to obstruct it. I cannot be part of that effort.” When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, and Germany and Italy declared war on the United States, America First closed its doors. Both Stuart and Brewster enlisted, Stuart in the Army, Brewster in the Navy. Yale turned over its campus to the war effort. By one count, 18,678 Yale students and alumni served; the names of 514 who died are inscribed in Memorial Hall. Lindbergh went to Washington to ask Stimson for a place in the military, but Stimson told him to go home. (In his diary, Stimson wrote that he was “unwilling to place in command of our troops as a commissioned officer any man who had such a lack of faith in our cause as he had shown in his speeches.”) Lindbergh later flew reconnaissance and combat missions in the Pacific, but without regaining his military status. He would never forget the warmth of his reception that night at Woolsey Hall, and he donated his papers and other personal materials to Yale. Stuart, who returned to Yale after the war to finish his law degree, followed his father as head of Quaker Oats. Brewster served Yale as its 17th president from 1963 to 1977, overseeing a campus once again inflamed by a bitter divide over a foreign war. He would leave Yale for the ambassadorship to Great Britain—the country on whose behalf he once hoped not to fight a war. While Stuart and Brewster, together with others on campus, had done all they could to avoid the war, ultimately Stimson was right: students at Yale proved “ready to take their proper part in this threatened world and to carry through to victory, freedom, and reconstruction.”

|

|

2 comments

-

Marc Wortman, 3:48pm July 06 2016 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

JOSEPH T MCCABE, 12:18pm July 08 2016 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.For more, go to: marcwortmanbooks.com

What are we to make of this article? To be proud or ashamed of Brewster? He brought about and presided over the "dumbing down" of Yale College.And he acted disgracefully here.

Thank God for the courage,foresight and wisdom of that Harvard man,FDR !!!